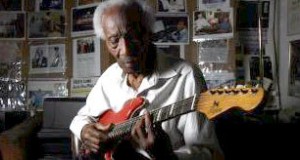

Photo of The Ink Spots Museum by Chris Becker

Being a recent transplant to Houston, Texas, I am only just beginning to take in the breadth and variety of the city’s cultural scene– especially its music. Each dispatch I bring to you from Houston will focus on contemporary composition, improvised idioms, and performances that integrate theatre, the visual arts, and/or dance. Inevitably, my love for rock, folk, blues, jazz, country, zydeco, and all out noise will creep into future writing, the overall goal being to expand peoples’ perception (including my own) of where one can find innovative forward-thinking music.

There may be a connection between Houston’s (lack of) zoning laws and the way that the past, present, and future inform each other throughout its landscape. Maybe that sounds like a cliche. But, if you’ve ever ridden the Houston’s Metro 80 bus through the Third Ward up Dowling Street, past Emancipation Park, and – just before turning left at Sparkle’s Burger Spot toward the glass cathedrals of downtown – observed an unfenced horse enjoying some grass in someone’s front yard, you know that I’m not talking some tourist board hogwash. There are many “zones” throughout this city dedicated to celebrating its history and nurturing its creative spirit. And they sometimes seem to appear out of nowhere.

The Ink Spots Museum (located in Houston Heights) is dedicated to archiving and celebrating the life and work of Texas born guitarist, singer, and educator Huey Long. The museum’s curator Anita Long (Huey’s daughter) welcomed my wife and I for a visit earlier this month and like many Houstonians I’ve met since our relocation from New York City, she was generous with her knowledge of Houston’s cultural scene. Every musician I know would take great comfort in knowing that a family member like Anita would take care of their legacy after they were gone. The museum and its accompanying website (featuring plenty of photos, audio, and video) serves to remind people that the history of American music includes the collective participation of many, many artists each committed to their respective craft. Which is one way of saying you might know that Huey Long was a member of The Ink Spots (from 1944 to 1946 with Bill Kenny as their leader), but not know he also played guitar in ensembles that included Dizzy Gillespie, Earl Father Hines, Sarah Vaughn, Charlie Parker, Fats Navarro, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, and many other luminaries of 20th century jazz and popular music.

Huey Long (who lived to be 105!) was born in 1904 in Sealy, Texas. For the people in Sealy as well as on the farms in surrounding areas, music was a vital part of a day-to-day dominated by hard labor (by the time he was a teenager, Huey was working as a sharecropper). Describing those formative years in Sealy in his pictorial autobiography The Huey Long Story, Huey recalls the names of no less than four different pianists (including his brother Sammy) playing “rags” on the pianos in people’s homes. “Ragtime” was indeed heard in Texas in the early 1900s as was what would become known as “the blues.” Huey’s sister Willie – also a pianist -studied music in Houston, at Wiley College, and brought back to Sealy classical and popular sheet music to play note for note when “grown ups” were in the house and improvise off of when the youngsters were on their own (some parents considered improvisation to be almost sinful behavior).

In addition to classical, popular, and ragtime music for piano, Huey was exposed to the up-tempo groove oriented music (my description) played on guitar at all night “suppers” (which included plenty of dancing, eating, and gambling on the various new betting sites) as well as its more somber and “sorrowful” counterpart known as “slow blues.” Huey began playing both guitar and piano, eventually moving to ukulele – a very popular instrument at the time. After setting out on his own at the age of fifteen and relocating in Houston, he began playing banjo (tuning it like a ukulele but an octave lower) and joined the Frank Davis Louisiana Jazz Band. This was a popular and well-respected band in its time, that played for both whites and blacks in Houston’s segregated communities. He would begin playing guitar after relocating from Houston to Chicago and joining Texas Guinan’s Cuban Band (who traveled to Chicago from New York City to play the 1933 World’s Fair). Later, Huey would join Fletcher Henderson’s Band and Earl “Father” Hines’ All Star Band (I apologize for skipping ahead a bit, and neglecting a lot of formative music making…)

Fast forwarding a bit…

Two sessions Huey did around 1946 with trumpeter Fats Navarro, tenor saxophonist Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, pianist Al Haig, bassist Gene Ramey, and drummer Denzil Best were released on two separate records: In The Beginning…Bebop (which is a compilation of sessions by three different bands) and of Fats Navarro’s recording Nostalgia. These recordings feature some truly kick ass guitar playing from Huey who definitely holds his own in the company of two phenomenally creative horn players. The rhythmic interplay between guitar and piano (and bass and drums…) is incredibly funky. This is bebop (probably) inspired by the music heard at Sealy’s all night suppers: Danceable, unpredictable, and filled with sly humor.

Teaching and composing music – including several chord melody solos based on themes from European Classical repertoire – would be a major part of Huey’s life along with researching his family tree creating an exhibit of his life’s work that would become The Ink Spots Museum. Anita talked to us about the possibility of the museum one day becoming a virtual exhibit – and there is plenty of history and music from Huey’s life as well as from Texas that should be shared with the world. For now, in addition to the website, there is this small museum – a standing structure in the midst of Houston’s un-zoned landscape – that you can make an appointment to visit.

Chris,

I really enjoyed this article. When I come to visit (hopefully soon) I certainly want to go!

Indeed. I should point out that lack of zoning has had both positive and negative impact on Houston’s landscape.

Real estate, zoning, and segregation (in all of its guises) profoundly affects the creative culture of any city. In New Orleans that’s very evident, you see it in Houston too, although you might have to dig a bit into the history of the various wards going back to the early 20th century to get a more complete picture.

Isn’t it amazing how many homes in the South had pianos or guitars back before the depression and on into the second World War?

Chris, the paragraph relating the Metro 80 to Houston’s lack of zoning is excellent. Not that I like the lack of zoning that has also resulted in the destruction of historical properties.

Playing ragtime when the adults were out of earshot also was sometime my mother described. She was one of 13 children, living on a farm in rural southwestern Ohio, and she and the other brothers and sisters would play rags and boogie-woogie on the piano if the parents were gone. The piano was supposed to be for classical and church music. This would have been in mid-1930s.

Chris, it was a delight meeting you and your wife, thank you for taking the time to write about The Ink Spots Museum and about my father, this is our Anniversary, we officially opened in the Houston Heights Historic District, TX, on June 19th 2007, “Juneteenth” also known as Freedom Day or Emancipation Day.

Dad was 103 years young and proud of his museum. (April 25, 1904 – June 10, 2009)