Report by Tyran Grillo (between sound and space)

Photos by Evan Cortens

Music: Cognition, Technology, Society set a formidable intellectual task before participants of the selfsame conference at semester’s end on the quieting campus of Cornell University. Under the attentive care of organizers Caroline Waight, Evan Cortens, Taylan Cihan, and Eric Nathan, what might have been an overwhelming conceptual storm proved smooth sailing through a series of back-to-back panels. The lack of overlap meant that everyone in attendance could take in the full thematic breadth and draw connections that might otherwise have been missed in the three-ring circus of a larger conference, thereby allowing interaction, a building of new relationships while strengthening the old, and dialogue conducive to the intellectual goals at hand.

The Panels

I had the privilege and the honor of presenting first in the opening Friday morning panel, entitled Patterns, Schemata and Systems, for which I was joined by Bryn Hughes (Ithaca College) and Joshua Mailman (Columbia). I did my best to set a tone in my discussion of Modell 5, a museum installation piece by Vienna-based duo Granular Synthesis, whose eponymous approach to motion capture and digital manipulation of synchronous sound and image activated, I hope, our shared interest in the intersection of technology and sonic arts. Hughes was interested in more mainstream sonic outlets. In problematizing expectation in rock music through harmonic progression as both a function of context and of socialization, he asked: Does harmony behave in a universal way? Why do some chord progressions sound “wrong” and how do we gain knowledge of these rules?

Hughes plotted a matrix of influences on such choices, discovering through controlled testing that expectations are genre-specific (diatonic successions, for instance, are preferred by classical over blues listeners) and that the impact of voice leading, lyrical (a)synchronicity, and other variables must also be taken into account. Mailman took a more phenomenological approach to music as a site lacking in expectation, advocating a cybernetic model of listening and feedback practices. In positing retrospection as an active shaping force of musical experience, Mailman privileged context over convention in musical structure. By looking at otherwise undeterminable aspects of musical form and development—what Boulez might group under the term “listening angles”—as a means of analysis, Mailman made a provocative case for cybernetic phenomenology as a viable site for sonic inquiry.

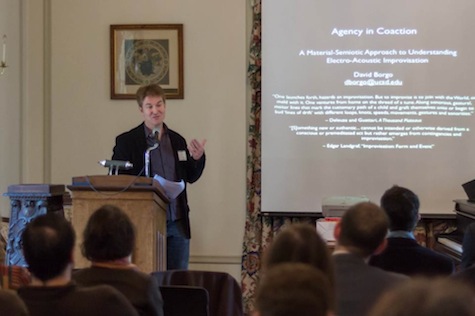

Qualities emerge through change and exist by virtue of being measured as such. Hence the assertions of David Borgo (UC San Diego), who in the second session on Improvisation challenged the dominant paradigm of musical spontaneity as an individual act, seeking rather to enlarge the notion of agency to its extra-corporeal aspects. Because action of response happens more quickly than consciousness can grasp, our interpretations of the very same can only come a posteriori, subject to the same misinterpretations as any and all memory. Consciousness, argued Borgo, is autopoetic and under constant perturbation. Improvisers must therefore negotiate contingencies in all directions. To locate them at the center of webs as amorphous as their melodic constitutions is as difficult as it is to locate the true center of a universe that is forever expanding.

Neither are improvisational gestures simply plucked from the ether, as Jeremy Grall (University of Alabama at Birmingham) showed in his exploration of the hierarchies at work in seemingly indeterminate music-making. Grall’s interest was the divide (or lack thereof) between composition and improvisation and whether or not the two can be subject to the same analytical vocabularies. For him, improvisation is an already problematic term, one that may be absorbed into composition insofar as improvisation abides by underlying schemata. In order to negotiate the ambiguities of perception and the phases of concrescence therein, he looked to 16th-century improvisational models and their inherent blend of immediacy and indeterminacy.

A fascinating Demonstration Session kicked off the conference’s first evening. William Brent (American University) gave us a visual and aural tour through his Gesturally Extended Piano and Open Shaper, while Mailman returned with Columbia colleague Sofia Paraskeva for a demonstration of their “comprovisational” interface. Both of these technologies take advantage of the primacy of the body in communicating information at once inter- and intra-musical.

Owen Marshall (Cornell) began Saturday’s first session, Technology and the Voice, with a timely look at the social politics of the Auto-Tune phenomenon. In doing so, he set off a new direction in the conference’s ongoing conversation by teasing out the deceptive and invisible elements of sonic production. Auto-Tune, noted Marshall, is a standard, and as such has become a ubiquitous aspect of the modern soundscape. Not only does it reassert time over interval as a primary audio marker, it equates loss of pitch with a loss of emotion, and metonymically substitutes the vocal tract for the Human. Carmel Raz (Yale) shifted gears yet again with an especially intriguing look at Ernst Toch’s Geographical Fugue, exploring a Benjaminian notion of afterlife through a piece that, although intended as little more than a musical joke, came to define the career of a composer whose depth has yet to be sufficiently recognized. Raz provided a much-needed corrective in this regard, situating Toch in a dizzying milieu of linguistic provocateurs and Weimar politics, and arguing the Fugue as a proto-electronic piece that even influenced John Cage, who was present at its premier.

The fifth session, Psychology and the Sonic Object, featured Alexander Bonus (Duke), who took us back to the turn of the twentieth century, when the notion of exactitude became testable through the advent of metronomic technologies. By thus explicating the influence of pathologized rhythm on the human body, Bonus explored our mechanical biases as they have developed in a society where precision is now a commonplace industrial value. This provocative paper incited some of the conference’s most spirited debate. Murray Dineen (University of Ottawa) explored even darker recesses of pathology in sonic realities, specifically the specter of monaurality and the falsehoods it brought to light in the labeling of projected sound. Confidence in equipment, quipped Dineen, is a belief, yet breeds within its permeable walls a confusion between life and sound (re)production. The latter is like imagination and leads to a deep-seated anxiety around infidelity—what he calls “monophilia.” Throughout this tale of users ever on guard against malfunction, Dineen kept his hat tipped whimsically toward nostalgia at every turn.

These philosophical turns were met by the sixth session, Instruments and Soundscapes, in which Jonathan De Souza (University of Chicago) explored James Gibson’s concept of affordances through instrumental design—specifically the harmonica—and how the acoustic interface is already a technological one in real time. In his attempts to understand how instruments influence players’ actions and how affordances, if innumerable, relate to idiomaticity, De Souza showed how instrumental idioms precisely make the affordances in question audible. Paul Chaikin (USC) then gave us a timely reexamination of the Schaferian keynote, turning an ear toward the socio-cultural importance of bells and bell ringing in Europe and the feelings these sounds engender in the listening citizen. Blurring line between active and passive listening, he set out to articulate the coherence of unmappable harmonies and polyrhythms inherent in the bell’s body and voice. Adem Merter Birson (Cornell) finished off the Saturday panels with a paper on the instrument maker’s art, highlighting the figure of the master lute luthier as an intersection of humanism and technology in Renaissance Italy. Detailing the natural laws of numbers in musical theory worked into every curve of said instrument, he showed the implicit philosophies of this appropriated and modified piece of technology.

The dedication of our crowd was further proven at a nearly packed house for the early morning Sunday session on Music Information Retrieval. Damien McCaffery (University of Glasgow) opened the conference’s closing panel by discussing our movement from a culture of hits to one of niches, the widespread filtering techniques (collaborative, content-based, context-based, and various hybrids thereof) that dictate our music listening, and the prescriptive effects of MIR on taste development. Next, Doug Turnbull (Ithaca College) proposed his own Megsradio.fm as an alterative to Internet radio players by which users may expand the possibilities of interface in MIR technology. Addressing the limited seeding options, lack of control mechanisms, and dearth of visual feedback in the top three (Pandora, Last.fm, Jango), Turnbull’s system provides a noticeably interactive experience, intelligent playlist algorithms, and, most importantly, a focus on local music. Last but far from least was William Brent, who expanded upon his demonstration with a look at the combinatory powers of gesture, responsive technology, and aesthetics. Focusing on timbre spaces as sites of real-time change, he complicated the symbolic/theoretical versus raw signal analysis in the act of performance.

The Keynotes

Scattered in between these cohesive panels was a handful of keynote speeches. The first came from Robert Gjerdingen (Northwestern), whose astounding breadth of knowledge pleased everyone through his look at the state of schema theory today. Through it he advocated a theory of exemplars, which states that long-term memory has no practical limit. Whenever we encounter something novel, be it a sound or image or experience, we inevitably compare it to the hundred, if not thousands, of exemplars that came before it rather than to some prototype. Thus do exemplar models preserve information about the correlation of different features. Everything we hear, he argued, we match against all else. Eric Clarke (Oxford) followed up with a well-synthesized talk on recordings as perception labs. So configuring the relationship between space and psyche as interdependent, Clarke set out to weave the complexities of event perception, environmental information, and attunement/immersion into a friendly philosophy of auditory proximities. Tod Machover (MIT) also gave a talk, sharing his insights into the extension of musical experience. He gave us a glimpse into the fruits of his research, which have seen the development of innovative technologies (Hyperscore), electroacoustic hybrids (Death and the Powers), and the latest developments in interactive performance (Remote Theatrical Immersion). Ichiro Fujinaga (McGill) had the final word, giving the closing address on his groundbreaking distributive model of digitization. His keynote detailed the immensely significant advances his teams have engendered in the field of optical music recognition (OMR), which allows for quick and easy digitization of musical scores as searchable entities. This left us with a remarkable vision of the future of technology and sound as seen through the prism of knowledge acquisition.

The Concerts

No music conference of such satisfying density would have been complete without performances to put theory into practice. And indeed, attendees were treated to a series of engaging events. The first of these came courtesy of the Cornell Avant-Garde Ensemble (CAGE), which gave an improvisatory performance on Friday afternoon. Its visceral congregation of electronics, oud, and various other instruments bowed, plucked, and otherwise cajoled into new vocabularies made for a fitting portal into the delicate balance of freedom and surrender that marked so much of the discussion at hand. The phenomenally talented Argento Ensemble, under the direction of Matt Ward, performed a lively potpourri of new works from student composers Sean Friar (Princeton), Bryan Christian (Duke), Juraj Kojs (Miami International University of Art and Design), Eric Lindsay (Indiana University), Amit Gilutz (Cornell), and Christopher Chandler (Eastman School of Music), and capped it all off with a 2006 piece by Machover. A concert of electroacoustic music provided a fitting close to the musical activities. Featuring works by Nathan Davis, Nicola Monopoli, Nicholas Cline (Indiana), Christopher Stark (Cornell), Peter Van Zandt Lane (Brandeis), Stelios Manousakis (Center for Digital Arts and Experimental Media), and the duo of Eliot Bates and Taylan Cihan (Cornell), it cycled through an array of sounds at once fresh, nostalgic, and undeniably get-under-your-skin delectable. For a more detailed and impressionistic account of the latter two shows, see my blog entry here.

Themes

I have always believed that the mark of a good conference is that it leaves one with more questions than answers. In this respect, the exciting goings on at MCTS 2012 succeeded brilliantly. In summary, however, I should like to offer a list of those points of confluence I saw working across the board:

- Schemata are active processes.

- Musical experiences and their aesthetics are malleable.

- Presentation, in any form, comes with its own immediacy.

- Consciousness is emergent.

- Musical scores are mnemonic devices.

- We can learn without understanding.

- Music and environment are interpenetrating.

- Sound is more substance than medium.

- Conventionality allows us to see the gorgeousness of details.

- Music is communication.

The last would seem the most appropriate note on which to end, for MCTS was about nothing if not communication. There is sound in all of us—breathing, vibrating, singing emotional threads of all colors and thicknesses—and it is through sound that we enter and leave this world. If an entire history can be expressed in a single motif, then I look forward to seeing the new chapters begun throughout this memorable May weekend as they unfold into the horizon.