Meredith Monk in review

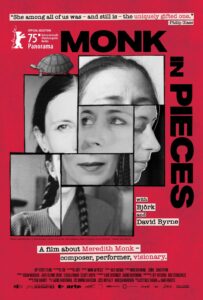

Meredith Monk has long attracted the attention of journalists and filmmakers intrigued by her synthesis of minimalism, vocalism and theater, and by her personality whose conversational informality camouflages a stoic tenacity that’s propelled one of the most iconic careers of any performing artist to come out of the New York avant-garde. Monk in Pieces, premiered in February 2025 and currently touring the global indie movie theater circuit, is the latest and most biographically-oriented entry in a line of Monk documentaries whose predecessors include Peter Greenaway’s 1983 portrait for BBC 4 (which remains a crucial guide to her early and most cinematically exploratory works) and Babeth VanLoo’s 2009 Inner Voice (which emphasizes her engagement with Buddhism, a topic that receives only glancing attention in Monk in Pieces).

What’s most notable about Monk in Pieces is that it shows its subject, who was 82 at the time of its release, preparing for the inevitable final chapter of her career, whose trajectory is traced in a broad (though not strictly chronological) arc, divided into a dozen-odd chapters each centered (as the title implies) on a particular major work. Helping to underscore the theme of mortality is Monk’s pet tortoise Neutron, given to her as a gift by Ping Chong in 1978, and the inspiration for her 1983 album Turtle Dreams. We hear Monk conversing with Neutron (Do you even know who I am…who’s fed you 42 years? It’s like, what does turtle consciousness tell me?), and nursing her through a fatal illness that leads into the film’s final and most touching scene in which Monk is shown by herself contentedly eating a simple supper in the kitchen of the Tribeca loft that’s been her home since 1972.1 Afterwards she cleans the table, the long takes poignantly accompanied by one of her earliest songs, Do You Be?, first recorded on her 1970 debut album Key (though the version used in the film is a later one from the eponymous 1987 album).

It’s Chong who contributes the film’s most candid and insightful commentary. Four years Monk’s junior, he enrolled in a class she was teaching at NYU in 1970, and then became her lover and company member. To the accompaniment of Madwoman’s Vision, he recounts how Monk once suggested that they have children together. I went, “Uh, I don’t think so! Artists shouldn’t have kids because the art comes first”. The tension between family and art turns out to be a recurring theme in Monk’s life. Chong eventually left Monk after a decade to focus on his own art (I wanted to be a director, and I kept giving her direction when she didn’t want it). And he attributes much of Monk’s career motivation to her strained relationship with her mother, the swing singer Audrey Marsh. (I think a lot of Meredith’s anger comes from not being valued by her mother. She just wasn’t there for her. And also she had to fight to be accepted in the performing arts world. In a way it’s a fight to survive. Pain is where art comes from, it has to come out of need. EM Forster stopped writing when he found his lover—he was too happy!).

Monk seems to concur with Chong’s assessment. As Marsh’s rendition of These Things You Left Me plays in the background (Marsh enjoyed great success as a young woman singing jingles for radio commercials before becoming yet another industry castoff), Monk recalls: She wasn’t home a lot. I was dragged around from job to job when I was a little kid, like going through a meatgrinder. I saw her pain of the conflict between being a mother and being an artist, and that both of them were not 100% satisfying. I vowed that that would never happen to me, and that I wanted to do my own work and make my own path.

Monk is much more circumspect when discussing her own emotions, in particular those surrounding the other major love interest of her life, the Dutch choreographer Mieke van Hoek, who like Chong was Monk’s student before becoming her partner of two decades. She’s seen only in still photos and silent vignettes, and it was her sudden death of cancer in 2002 that inspired Monk’s Impermanence. But though Monk concedes that I learned more from [her death] than from anything [else] that ever happened to me—I wasn’t the same person after that, she declines to tell us just what she learned or how she changed. In contrast to Chong, Monk is a person who only reveal her vulnerabilities through her art.

The remainder of the film is built from a montage of mementos, reflections, performance footage, excerpts from Monk’s dream journals (accompanied by cutout animations by Paul Barritt), and testimonials by various colleagues and collaborators, some of them archival (Merce Cunningham, who died in 2009), others shot specifically for the film (New Sounds host John Schaefer). Björk makes an appearance on behalf of the younger generation, recounting the impression made by Monk’s 1981 Dolmen Music album when she first heard it on her boyfriend’s record player at the age of 16. As the soundtrack fades from Monk’s rendition of the track Gotham Lullaby to Björk’s own 1999 cover with the Brodsky Quartet, the uninhibited Icelandic singer, apparently harboring a dim view of lower Manhattan, opines her loft that she’s lived in for half a century is an oasis in a toxic environment, and I feel that Gotham Lullaby represents that as well.

In another vignette Monk describes the strabismus (eye misalignment) that plagued her as a child. I wasn’t able to see out of both eyes simultaneously, so her mother took her to Dalcroze eurhythmics from ages 3–7 to help with the integration of body and rhythm. Monk approvingly cites Dalcroze’s assertion that “all musical ideas come from the body”. (Ding! I think that’s where I’m coming from.). And on other occasions she’s credited Dalcroze with “influencing everything I’ve done. It’s why dance and movement and film are so integral to my music. It’s why I see music so visually”—a key to what may be the most fundamental difference between her approach and the more formal and abstracted patterns of the classical minimalists.

Monk In Pieces is very much an in-house affair. It was co-produced by longtime Monk ensemble member Katie Geissinger, whose husband, Billy Shebar, directed it. And as might be expected, it occasionally drifts into hagiography, most notably in the montages of bad reviews and—in the case of Atlas (1991)—snarky communications with Monk’s collaborators at Houston Grand Opera, all combining to reenact the time-honored legend of the misunderstood genius who’s ultimately vindicated. Chong too contributes to this trope (“Critics were saying that what she was doing was nonsensical, was crazy, was not serious.”), and it’s true that Monk received negative press from the notoriously snobbish Clive Barnes during the 1970s. But other critics from that time were supportive, including Barnes’ New York Times colleague Anna Kisselgoff, who praised the 1969 debut of Monk’s Juice at the Guggenheim Museum. Notwithstanding her detractors, it was the modern dance community, already largely dominated by women, that took Monk seriously long before she established a reputation among musicians. Ironically by the mid-1980s these perspectives had largely flipped, with composers reacting to the newfound sophistication and longform exploration of Dolmen Music (compared to the more embryonic Key and Our Lady of Late), while dancers began to dismiss her choreography as amateurish (“They’re just doing shuffle steps in unison”).

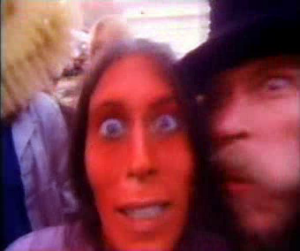

I would have appreciated hearing less from the talking heads (including original Talking Head, David Berne) and more about Monk’s early years, especially her time in Los Angeles in the late 1960s when she belonged to Frank Zappa’s extended circle (she appeared as the ”Red Face Girl” in Zappa’s film Uncle Meat, and her music director was Mothers of Invention keyboardist Don Preston, who is still alive and lucid in his 90s). It’s also curious that despite being in relatively close proximity to the Bay Area origins of classic minimalism, that Monk seldom talks about La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Stimmung, or the triumvirate of Riley, Reich and Glass as formative influences. But these are professional quibbles, and regardless it’s gratifying to revisit many of the now-obscure source materials, including Phill Niblock’s 1969 film documentation of Juice.

On the heels of Monk in Pieces comes Cellular Songs, Monk’s latest release for the ECM label, extending an illustrious discography that commenced with Dolmen Music, and which now encompasses 13 albums, of which the first twelve were repackaged and given an new and expanded accompanying booklet in the 2022 compilation Meredith Monk: The Recordings, cherishingly assembled by ECM for the composer’s 80th birthday (it was one of my picks for that year). It features Monk’s all-female vocal ensemble in a medley of mainly a cappella songs, occasionally accompanied by piano, simple percussion instruments or body percussion in the tradition of hambone. Only one of the songs (Happy Woman) has a text. In the aforementioned Peter Greenaway documentary Monk proclaims “I don’t really have contempt for the word. I have contempt when the word is used as the glue of something, which has happened in theater and a lot of film.”). Indeed, it’s Monk’s avoidance of texts that has helped keep her often joyful music from running aground on the shoals of sentimentality.

The titular reference of Cellular Songs is to biological cells, “the fundamental unit of life”, not to mobile phones. And its music is subdued but affirmational. In Monk in Pieces, the composer says “In the 80s I was doing apocalyptic pieces [e.g., Quarry and Book of Days], and then I started thinking about how maybe offering an alternative was more useful.”. With her still-capable but undeniably aging voice in the forefront, the proceedings read like a bookend to Dolmen Music, a gentle lullaby for the Monk faithful from the twilight of her career.

The titular reference of Cellular Songs is to biological cells, “the fundamental unit of life”, not to mobile phones. And its music is subdued but affirmational. In Monk in Pieces, the composer says “In the 80s I was doing apocalyptic pieces [e.g., Quarry and Book of Days], and then I started thinking about how maybe offering an alternative was more useful.”. With her still-capable but undeniably aging voice in the forefront, the proceedings read like a bookend to Dolmen Music, a gentle lullaby for the Monk faithful from the twilight of her career.

When assessing the oeuvre and legacy of Meredith Monk, there’s a sum-of-the-parts factor that’s hinted at by a Philip Glass quote heard in Monk in Pieces: “The thing about Meredith is, she was a self-contained theater company. She among all of us was the uniquely gifted one [as a performer].” Monk’s vocal talents, including a three-octave range and command of ululations and other extended techniques, are undeniable. And her emphasis on the voice distinguishes her from the classical minimalists, including Glass, who tended to regard singers as yet another ensemble instrument. As a composer, choreographer, pianist, dramatist and theatrical jill-of-all-trades, though, Monk has often been accused of flirting with dilettantism, especially during the decade prior to Dolmen Music. An interesting precedent I think is Alwin Nikolais, who began as a musician, learned the theatrical crafts of lighting and costuming and ultimately became known primarily as a choreographer. Today he’s seldom cited by specialists in any of those fields. It was the totality of the Nikolais experience, the futuristic visual and auditory spectacle, that’s driven his influence and reputation.

Interestingly, one of Monk’s key teachers at Sarah Lawrence College was Nikolais alum Beverly Schmidt Blossom. And Monk’s greatest impact may likewise be in the holistic domain of new music theater, an area where she’s retained her avant-garde bona fides, eschewing text-centric linear narratives (and the lucrative operas commissions that Glass retreated to after Einstein on the Beach) in favor of wordless, non-linear forms, often involving female-centric narratives. On Education of the Girlchild (1973) Monk has said “I don’t really feel that by nature I’m a political artist. The piece has six women characters. Usually you’ll see men-bonded groups like The Seven Samurai or the Knights of the Round Table. You don’t usually see six strong women who are not angry women but are just fulfilled women as the main heroes of an artwork”. Monk may ultimately be judged most favorably for building a corpus of aesthetically radical, often female-centered theater works that avoid the clichés of both strident militantism and New Age sentimentality.

Toward the end of Monk in Pieces, Monk seems to embrace a sentiment expressed earlier by Ping Chong: “Doing the work is still meaningful. The other stuff just falls away. Maybe this whole thing is a way that I created something to affirm that I exist.” Whether or not a Monk devotee will find anything genuinely new in this film or in Cellular Songs, they both do justice to a career that’s remarkable for its resilience, persistence and impact.

[1] a six-story L-shaped building on West Broadway that also once housed Roulette Intermedium