Theo Plath et al.: Zelenka Trio Sonatas / Ko Ghosts

Some composers refine the language they inherit. Others trouble it, bend it, and compel it to confess what it would rather conceal. Jan Dismas Zelenka (1679-1745) belongs to the latter lineage. His music does not decorate Baroque convention so much as interrogate it from within, testing how much strain the form can bear before it reveals something truer than elegance.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the six Trio Sonatas, ZWV 181. To encounter them is to overhear the composer thinking aloud: restless, contrarian, devout, and faintly dangerous. Zelenka came to Dresden as a virtuoso of the orchestra’s lowest voice, the violone (the double bass of the viol family), and perhaps it was from this subterranean vantage point that he learned to hear differently. The Saxon court offered refinement, virtuosity, and an unspoken mandate to please. Zelenka responded by writing music that does not flatter. His themes resist symmetry; his counterpoint knots itself into elongated sentences; his harmonies wander into regions that contemporary theory would have marked for correction. What others might have called errors, he transformed into intensifiers, harmonic abrasions that heat the music from the inside.

History, predictably, treated him with reserve. While smoother contemporaries secured lasting renown, Zelenka remained a kind of well-kept secret, indispensable yet peripheral. His sacred works never entirely vanished, but his chamber music receded into manuscript silence, waiting for ears able to hear its strangeness not as deviation, but as intent.

The Trio Sonatas stand at the center of that rediscovery. Built from the same instrumental forces, each inhabits a distinct emotional climate. Zelenka’s preference for the bass over the cello pulls the continuo downward, thickening the ground beneath the music until it seems to resonate from the floorboards up. Above this darkened foundation, oboes and bassoon are driven to virtuosic extremes, not for display, but as expressive necessity. Their lines speak urgently, sometimes breathlessly, demanding a commitment that still challenges modern players.

These sonatas remind us that modernity is not a question of dates. Long before the term acquired its present meaning, Zelenka was already there, privileging expression over obedience and writing music that still seems to run just ahead of us. This recording arrives as an act of listening across time, alert to challenge, depth, and the rare pleasure of being unsettled.

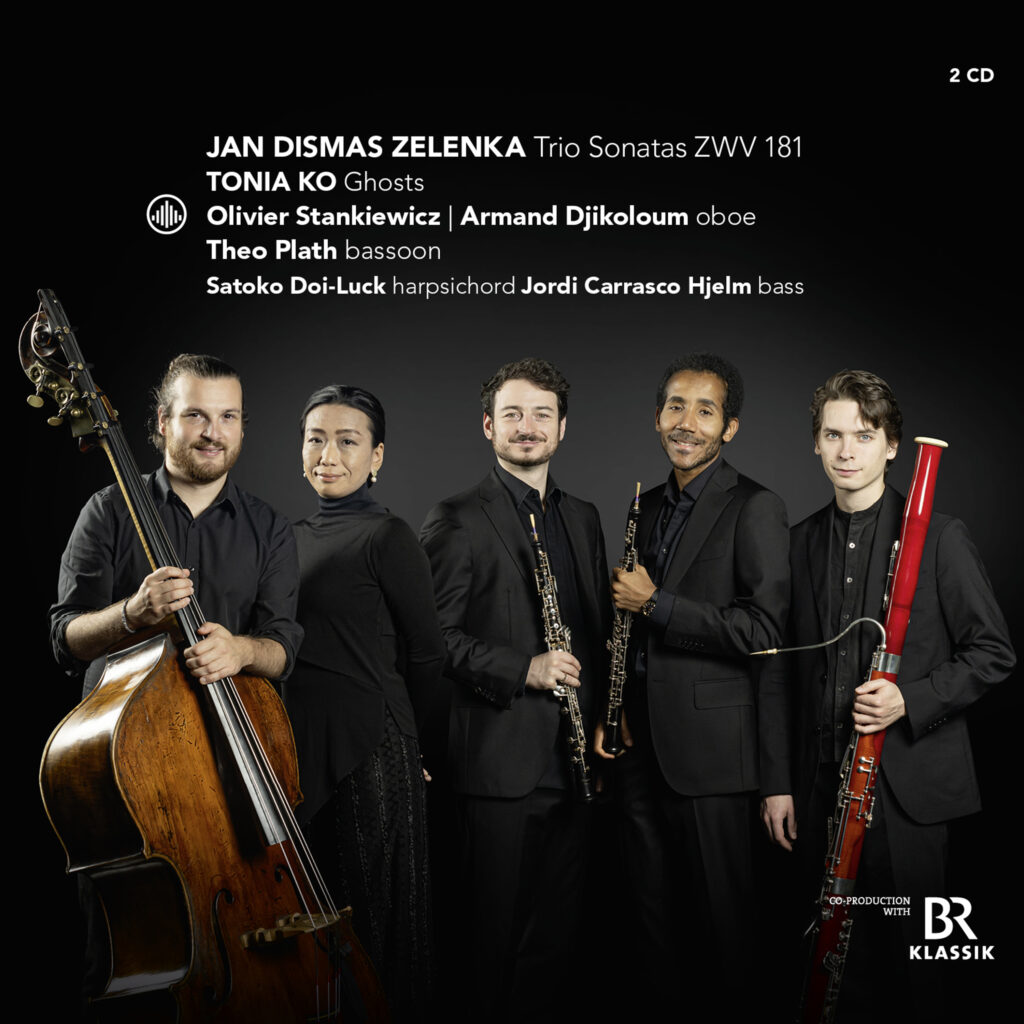

Having long been enchanted by these works through the touchstone recording by oboists Heinz Holliger and Maurice Bourgue on ECM New Series, it is deeply gratifying to hear them rendered here with such acuity. The shared articulation of Olivier Stankiewicz and Armand Djikoloum on the higher reeds flows with liquid assurance, immediately evident in the opening movement of the Sonata No. 1 in F Major. Beneath them, Theo Plath’s bassoon and the continuo team of Satoko Doi Luck on harpsichord and Jordi Carrasco Hjelm on bass provide both sparkle and shadow, creating a terrain generous enough for the leading voices to roam. The enlivening second movement charms through its seamless entanglements, yet it is in the slower movements that deeper mysteries surface. The Larghetto of the third movement unfurls like a scroll read in real time, its measured pace allowing space for reflection. A similar spirit animates the two Andantes of Sonata No. 2 in G Minor, whose presence keeps the Allegro they embrace from tipping into self-indulgence. Taken together, they suggest a narrative that resolves not through closure but through remainder.

Elsewhere, vitality abounds. The opening Adagio of Sonata No. 3 in B flat Major offers a moment of restoration, its architectural details haunting yet finely chiseled, making no attempt to disguise their craft. The buoyant second movement of Sonata No. 4 in G Minor lifts the spirits, even as the following Adagio gently arrests the heart. Sonata No. 5 in F Major closes with a tessellated dance, richly patterned and quietly exuberant. Yet it is Sonata No. 6 in C Minor that delivers the program’s most decisive statement. From its lush Andante overture to the final dance, it lays its cards on the table with utter indifference to the hands we hold. The Baroque equivalent of a mic drop, delivered centuries before the gesture had a meme.

Some music does not so much return from history as refuse burial. Ghosts (after Zelenka) emerges from that unsettled terrain where fragments of the past hover, half-remembered yet insistently present. Composed in 2023 by Tonia Ko for the same instrumental forces, it draws its material from one of Zelenka’s most inward utterances, Caligaverunt oculi mei from the Responsoria pro Hebdomada Sancta, ZWV 55, a work already steeped in darkness, exhaustion, and spiritual vertigo.

Rather than unfolding as a series of discrete movements, Ghosts is interwoven between Zelenka’s sonatas. In such an orientation, it behaves like a slow psychological weather system. The predecessor’s lines are dismantled and reassembled, stretched until they breathe unevenly, then allowed to fray. Respiration becomes material. Silence acquires weight. Counterpoint strains against itself, while harpsichord points scatter like sparks, each one briefly illuminating a surface before fading. Extended techniques in the bass destabilize the ground, reminding us how quickly even unconventional harmony can harden into habit once it is named.

As the work progresses, contemplation gives way to disturbance. Musical images waver as if seen through water, growing more unstable the harder one tries to fix them in place. Bassoon and oboes ignite quiet flares, sometimes slipping into multiphonics, while the harpsichord registers each eruption as a tiny extinction, a sound allowed enough time to vanish properly. What might once have been melody becomes contour, then memory, then pressure.

Gradually, ascent reveals itself as inversion, an auditory parallax in which direction itself becomes unreliable. Precision and openness coexist. Structures appear only to hollow themselves out from within, leaving space for personal truths to surface among the fragments. By the time the music recedes, what remains are not themes or gestures, but footprints, carefully shaped, tracing where something passed without ever fully arriving.

Zelenka’s sacred music has always felt perilously close to the surface of the skin. Its intensity is bodily rather than rhetorical, belief rendered as something strained to the point of rupture. In Ghosts, that intensity passes through Ko’s unforced language, shaped by unstable timbres, an attraction to collapse, and a fascination with sound as something that remembers being sound. The instruments no longer sing as they once did. They rasp, breathe, tremble, and withdraw, as if struggling to recall a former speech.

Taken together, the Trio Sonatas and Ghosts do more than converse across centuries. They expose composition itself as an act of risk. To listen closely is to accept instability, to relinquish the comfort of resolution, to allow meaning to arrive sideways or not at all. Zelenka’s music does not ask to be preserved behind glass. It asks to be entered, argued with, and trusted despite its refusal to reassure. Ghosts does not answer that request. It extends it into the present tense.

What lingers after the final sound is not silence but a charged quiet, the feeling that something beneath the surface has shifted position. The ground no longer feels inert. It listens back. And in that reciprocal attention, history stops behaving like a line and begins to resemble a field, one in which the past does not recede. It waits, alert, for those willing to step carefully and hear what still insists on speaking.