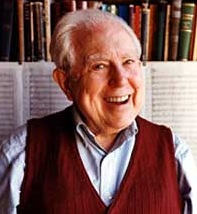

At 66, baritone Thomas Buckner says he’s busier now than he was when in his forties. Last month, when we sat down to chat, he had just come back from a week of master classes and music making at Mills College. Next week, he has a terrific-sounding concert at Greenwich House, and, in June, he’ll play a leading role in a festival featuring Robert Ashley’s operas in Ferrara, Italy. This is all in addition to the Interpretations concert series, which he curates, and running his record label, Mutable Music.

At 66, baritone Thomas Buckner says he’s busier now than he was when in his forties. Last month, when we sat down to chat, he had just come back from a week of master classes and music making at Mills College. Next week, he has a terrific-sounding concert at Greenwich House, and, in June, he’ll play a leading role in a festival featuring Robert Ashley’s operas in Ferrara, Italy. This is all in addition to the Interpretations concert series, which he curates, and running his record label, Mutable Music.

Though growing up he was an enthusiastic participant in family holiday sing-alongs, when he went off to Yale, it was expected he would go into business like the rest of his family. But in his Sophomore year he dropped out and went west. After working in a factory for a year, he re-enrolled in college at UC Santa Clara, majoring in English. While at Santa Clara, Buckner began to exercise his composition chops by writing incidental music for drama club productions. Soon the town came to host a summer Shakespeare festival; he scored their shows, and, gradually–propelled in part by a performance of Webern’s five pieces for string quartet–he found himself gravitating to the experimental music scene.

During the late 60s and into the 70s, Buckner was busy as a composer, singer, and impresario. His music company, 1750 Arch Records (named after its address in Berkeley), produced hundreds of concerts of avant-garde and experimental music, and, soon, LPs as well. But a trip back to New York in 1979 planted in him the idea to join the vibrant scene back east as a singer, a role which, he felt, ultimately suited him better than composition. Though he considered moving to France because of some satisfying work he had done there, Buckner decided to stay in the States and be a part of his native musical culture.

Soon after he moved back East, the recording market began to turn towards CDs, and, instead of trying to transfer 1750’s catalogue to the newer medium, he reformed the label as Mutable Music and began producing CDs featuring the music of composers and performers who, like Webern years before, showed him new things music could do. Buckner enjoys the freedom and collaborative nature of experimental music and is a frequent performer (and teacher) of vocal and group improvisation. His concert at Greenwich House, however, will be more straightforward that his usual projects. He wanted to present an evening of song. On the program are songs about love and songs that tell stories. Texts come from such stand-bys as Percy Shelley, e.e. cummings, and Walt Whitman. The composers, however, are among Buckner’s fresh-voiced comrades: Noah Creshevsky, Roscoe Mitchell, W.A. Mathieu, and others share the spotlight. Attendance is urged.

This Saturday night at Greenwich House, composer

This Saturday night at Greenwich House, composer  II.

II.

Emerging from Elliott Carter’s “What Next?” for me paralleled uncannily the experience of the characters onstage, all of whom have just endured “some kind of accident” whose significance and impact, however powerful, remain baffling. Details from the libretto and the set design suggest a multi-car collision has occured, and, amid the wreckage, the victims intermittently soliloquize about their plight and attempt to comfort each other, though all — physically, at least — are unhurt. But an absurd, profound interpersonal disconnect ultimately predominates, and the opera ends with a pair of oddly fastidious road workers who, after they clear the debris, lead the accident victims to safety.

Emerging from Elliott Carter’s “What Next?” for me paralleled uncannily the experience of the characters onstage, all of whom have just endured “some kind of accident” whose significance and impact, however powerful, remain baffling. Details from the libretto and the set design suggest a multi-car collision has occured, and, amid the wreckage, the victims intermittently soliloquize about their plight and attempt to comfort each other, though all — physically, at least — are unhurt. But an absurd, profound interpersonal disconnect ultimately predominates, and the opera ends with a pair of oddly fastidious road workers who, after they clear the debris, lead the accident victims to safety. Two contemporary African-American composers shared the spotlight with Bach, Turina, Ellington, and Piazzolla at the

Two contemporary African-American composers shared the spotlight with Bach, Turina, Ellington, and Piazzolla at the