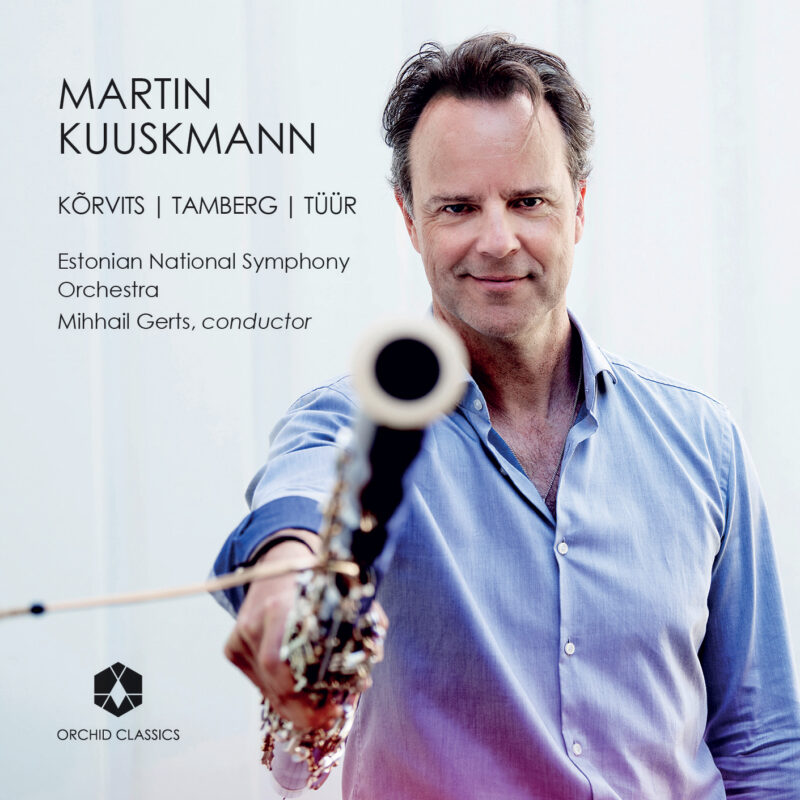

Martin Kuuskmann performs works for Bassoon and Orchestra composed by Tõnu Kõrvits, Eino Tamberg and Erkki-Sven Tüür, with the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra conducted by Mihhail Gerts on Orchid Classics ORC 100384 ©2025 by Orchid Music Ltd. Martin Kuuskmann (b. 1971) is an Estonian born, multi-Grammy nominated virtuoso bassoonist noted for his high energy, charismatic performance style across a wide spectrum of idioms and repertoire. To date, over a dozen concerti have been written expressly for him. In addition to maintaining a busy international recording and concertizing career, he holds the chair of Associate Professor of Bassoon at the University

Read moreDAY It’s been said (probably by Robert Craft) that Stravinsky was the last composer whose work could survive a one man recital. At yesterday’s performance of the complete Sequenzas at the Rose Theater, I heard that mantle happily passed by 14 brilliant advocates to Luciano Berio. In his introductory remarks for yesterday’s performances composer & host Steven Stuckey said that when Berio wrote the Sequenza I for flute in 1958 he didn’t know that he was starting a dynasty. I wonder. By 1958 Berio was already fashioning an approach to composition consciously modeled, down to the smallest detail, on the

Read more