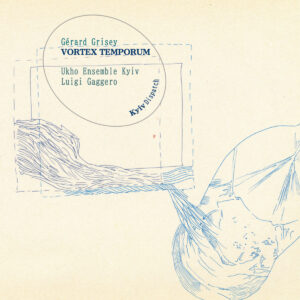

Gérard Grisey – Vortex Temporum

Ukho Ensemble Kyiv, Luigi Gaggero, conductor

Self-released LP

Composer Gérard Grisey (1946-1998) employed methods that often involved magnifying seemingly small details into overarching concepts. This is particularly true of spectrographic measurements taken of single pitches, such as the low E on a trombone, which revealed a series of overtones that he would use to craft harmonic systems for a number of pieces. This spectral approach, also employed by Tristan Murail, Hugues Dufourt, James Tenney, and others, was an important feature of French music, and later that in other countries, from the 1970s onward. In the piece Vortex Temporum (1995), another element is put under the magnifying glass, a flute arpeggio taken from Daphnis et Chloé (1912) by Maurice Ravel (1875-1927). The result is a hyperintensive investigation of, as the title suggests, circular motion through time. Scored for a Pierrot ensemble – flute, clarinet, violin, viola, cello, and piano – the piece does not leave Grisey with as many of the nuances of color that a full orchestra would, but he nevertheless manages to explore myriad timbral deployments.

A subtext that surely did not escape the notice of the piece’s intended audience is the fragmentation of the source material, in a sense the disassembling of a work firmly ensconced in the repertoire. Just as, in their day, the impressionists threw down a gauntlet and challenged the musical establishment, and Boulez and other members of the avant-garde did similarly with their elders, so Grisey and the other spectralists were interested in a radical reassessment of how music was to be ascertained.

Ukho Ensemble Kyiv take a deconstructive approach of their own, providing a charged, intense, and incisive rendition of Vortex Temporum. Any reference to impressionism, besides the notes and gesture of the borrowed quote, is removed from consideration. This is faithful to the score and Grisey’s musical aesthetic. Interesting to note, too, that the Pierrot ensemble signifies a connection to modernism; from Schoenberg to the present day it has been a go-to scoring for countless post-tonal composers.

While there are places in the outer movements that are quite forceful, there are also segments, such as the denouement of the first movement into the opening of the second, with a number of glissandos, where the music seems to liquefy. But a sense of conflict is never far away, as the muted clusters in the piano that support this passage suggest, and eventually the oasis of the middle movement is supplanted by intensity, led by nervous microtones and multiphonics and a crescendo of the piano’s dissonant verticals that is doubled by other members of the group. The strings also respond in kind to the clarinet’s effects, and the resultant music builds in amplitude to a hushed cadenza of descending slides, followed by a return to the first movement’s assertiveness in the final one.

This third large section expands upon the way that the Ravel quote is addressed, via fragmentation, augmentation, and interpolations of the effects that sound in the second movement. The sense of reverberation is enlarged as well, and many phrases echo instead of having clean offsets. Then, a pizzicato strings passage moves to the fore. It could be seen as a bit of sly commentary on the second movement of Ravel’s string quartet, which contains a plethora of plucked notes. This is then juxtaposed with ever more frenetic arpeggiations and glissandos, overblown wind notes, and penetrating sustained pitches. All of this underscores temporal morphing, and it is made manifest that the title serves as both a reference point and a remit for the composition. Several sections of quietude are each in turn cast aside in favor of ever more intricate sonic whirlwinds. An eventual unwinding once again stretches out the material, with explosive interruptions keeping the intensity level at a peak. Hushed moments then crosscut with vicious attacks and fluctuating lines, and a long tremolando creates a dynamic hairpin. What ensues in its wake is reflective, with breathy woodwinds, sustained strings, and a tolling repeated note from inside the piano in a decrescendo to silence.

Vortex Temporum is a late piece in Grisey’s catalog. He died in 1998, at age 52, of a brain aneurysm. It fulfils a number of the objectives he set out to explore, both from technical and philosophical vantage points. Luigi Gaggero leads the Ukho Ensemble in a superb rendition of the piece. It is one of my favorite recordings of 2025.

- Christian Carey