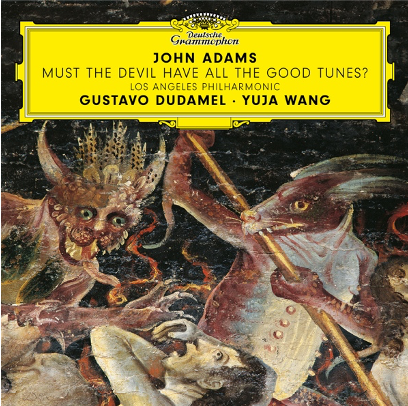

John Adams

Why Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes?

Yuja Wang, piano; Los Angeles Philharmonic, Gustavo Dudamel, conductor

Deutsche Grammophon

Thomas Adés

Adés Conducts Adés

Kirill Gerstein, piano: Christianne Stotijn, mezzo-soprano, Mark Stone, baritone;

Boston Symphony, Thomas Adés, conductor

Deutsche Grammophon

This year saw the release of two formidable new piano concertos on Deutsche Grammophon: John Adams’s third piano concerto, titled Why Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes? (a quote from Martin Luther about using popular melodies as chorales), and a concerto by Thomas Adés. The recordings feature two of the most dynamic soloists active today, pianists Yuja Wang and Kirill Gerstein. The Adés release also includes Totentanz, an impressive vehicle for mezzo-soprano Christianne Stotijn and baritone Mark Stone.

Adés has crafted a piano concerto that pays homage to past pieces in the genre, with more than a passing nod at those by Ravel and Gershwin. Buoyancy typifies the outer movements, with jaunty swinging passages appearing in both, but the middle movement is a searing adagio in which dense harmonies are set against a poignant piano solo. Gerstein is extraordinary in his virtuosity and versatility. His playing is particularly impressive during the latter portion of the third movement, where weighty terrain reminiscent of the second movement is once again encountered, at the last possible second veering back to the fast demeanor of the opening and a brilliant cadenza followed by a strongly articulated final cadence.

In Must the Devil…, Adams displays the polyglot language he has cultivated since the 1990s, in which the post-minimalism of his earlier works takes on the role of a background grid while rich harmonies, American pop references, and a demanding solo part take the fore. The first movement is marked “gritty, funky, and in strict tempo,” and the rockabilly riff that Wang and the orchestra lock into propels the action. It is succeeded by a double time riff from the orchestra over which Wang plays incisive chords and fleet runs. A cadenza deconstructs the riff into angular punctuations and arpeggiations. The second movement features delicate shadings of repeated pitch cells and frequent trills haloed by long descending scales in the strings. Gradually, counterpoint in the winds joins the proceedings and the piano part thickens to lush textures. Textures dissolve until we are left with pointillist versions of the original arpeggiations. Repeated chords lead attacca into the third movement, the repeating pulse undertaken by the orchestra while the piano takes up a wide-spanning perpetual motion figure. A vigorous march, punctuated by chimes and brass and thick chords in the piano supplants this, eventually offset by a triplet riff that gives us just a hint of the piece’s opener. Moving back and forth between double time iterations and solid beat-note blocks of sound, the stage is set for a flurry of activity from the piano. The soloist and orchestra interlock in a brisk groove that periodically is interspersed by mini-cadenzas. The coda takes on a machine like ostinato that ends vigorously. Wang’s encore is China Gates, one of Adams’s prominent early works that has stood the test of time. Here and in the concerto, her playing is superlative, vivacious, and detailed.