American composer Tom Myron was born November 15, 1959 in Troy, NY. His compositions have been commissioned and performed by the Kennedy Center, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Portland Symphony Orchestra, the Eclipse Chamber Orchestra, the Atlantic Classical Orchestra, the Eastern Connecticut Symphony Orchestra, the Topeka Symphony, the Yale Symphony Orchestra, the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, the Bangor Symphony and the Lamont Symphony at Denver University.

He works regularly as an arranger for the New York Pops at Carnegie Hall, writing for singers Rosanne Cash, Kelli O'Hara, Maxi Priest & Phil Stacey, the Young People's Chorus of New York City, the band Le Vent du Nord & others. His film scores include Wilderness & Spirit; A Mountain Called Katahdin and the upcoming Henry David Thoreau; Surveyor of the Soul, both from Films by Huey.

Individual soloists and chamber ensembles that regularly perform Myron's work include violinists Peter Sheppard-Skaerved, Elisabeth Adkins & Kara Eubanks, violist Tsuna Sakamoto, cellist David Darling, the Portland String Quartet, the DaPonte String Quartet and the Potomac String Quartet.

Tom Myron's Violin Concerto No. 2 has been featured twice on Performance Today. Tom Myron lives in Northampton, MA. His works are published by MMB Music Inc.

FREE DOWNLOADS of music by TOM MYRON

Symphony No. 2

Violin Concerto No. 2

Viola Concerto

The Soldier's Return (String Quartet No. 2)

Katahdin (Greatest Mountain)

Contact featuring David Darling

Mille Cherubini in Coro featuring Lee Velta

This Day featuring Andy Voelker

|

|

|

|

|

Tuesday, June 21, 2005

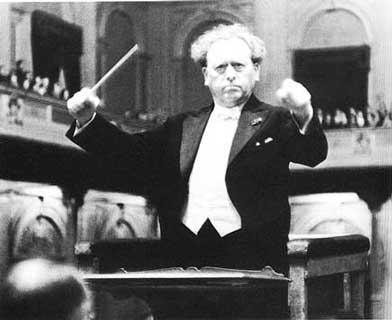

The Conductor In My Life

In response to Carmen Helena TÚllez's inaugural post today, with its inquiry about the composer/conductor dynamic, I submit the following:

When writing for orchestra experience is the only teacher. I have had the great good fortune to work very closely with several first-class conductors on the presentation of my work. In fact, without these individuals I doubt that it would have occurred to me to write for orchestra. Now the passion and artistry that they have brought my work is the engine that drives my inspiration.

Sylvia Alimena and the Eclipse Chamber Orchestra have committed major talent and resources to the realization of a sequence of string concerti. Andrew McMullan not only commissioned my Symphony #2, he embraced the project so completely that for two seasons he conducted it from memory. And then there is Toshiyuki Shimada, who for the past twelve years, with a degree of belief and generosity that is almost hard for me to comprehend, has made the Portland Symphony Orchestra the center of my musical universe.

Here are some things that I've picked up during this time.

A conductor doesn't just know your score. She or he knows the hall, the individual players and, most importantly, the group dynamic during any given set of services. If you attend the first rehearsal, hang back and wait to be asked any questions. I don't care what kind of things you're hearing from the stage, this is the time when the conductor is getting a feel for the musician's grasp of your piece. It will set the tone for all decisions to follow and you interfere with it at the peril of your work.

When you are asked a question keep cool and make your answers concise. If you're listening from the back of the hall, move quickly down to the front. Do not attempt to yell detailed interpretive theories from the back of the house. Speak only with the conductor. Never address the orchestra or individual players without his or her permission (unless you have an extremely funny joke to tell.)

But don't be cowed either. It's taken me years to understand just what it means that at this point nobody but you knows precisely how your piece goes. Think about it for a second- as far as the players on stage know the thing may not work at all. But you know otherwise and if you stay calm while they figure that out it's a huge respect earner.

I pay very close attention when a conductor has a suggestion about the relationship between the overall balance of a passage and the way individual parts are marked. Toshi in particular has made many practical suggestions to me about what markings I might put in a score to get exactly the effect I'm after without changing notes or orchestration. When the conductor stops the orchestra and asks you about a specific note in a five-part texture (this used to be a sure-fire brain-freezer for me) don't be afraid to ask to hear the passage again. It's very relaxing- you've just made the orchestra play- and you will hear either the note in question or you'll hear that there really is nothing wrong.

And finally, the conductor has devoted a huge amount of psychic energy learning the intimate details of your brainchild. Do yourself a favor and learn something about the conditions under which they perform their jobs. A working knowledge of the orchestra business will give you credibility on the job and go a long way towards removing the veil of mystery that many composers feel enshrouds the field.

posted by Tom Myron

|

| |