American composer Tom Myron was born November 15, 1959 in Troy, NY. His compositions have been commissioned and performed by the Kennedy Center, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Portland Symphony Orchestra, the Eclipse Chamber Orchestra, the Atlantic Classical Orchestra, the Eastern Connecticut Symphony Orchestra, the Topeka Symphony, the Yale Symphony Orchestra, the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, the Bangor Symphony and the Lamont Symphony at Denver University.

He works regularly as an arranger for the New York Pops at Carnegie Hall, writing for singers Rosanne Cash, Kelli O'Hara, Maxi Priest & Phil Stacey, the Young People's Chorus of New York City, the band Le Vent du Nord & others. His film scores include Wilderness & Spirit; A Mountain Called Katahdin and the upcoming Henry David Thoreau; Surveyor of the Soul, both from Films by Huey.

Individual soloists and chamber ensembles that regularly perform Myron's work include violinists Peter Sheppard-Skaerved, Elisabeth Adkins & Kara Eubanks, violist Tsuna Sakamoto, cellist David Darling, the Portland String Quartet, the DaPonte String Quartet and the Potomac String Quartet.

Tom Myron's Violin Concerto No. 2 has been featured twice on Performance Today. Tom Myron lives in Northampton, MA. His works are published by MMB Music Inc.

FREE DOWNLOADS of music by TOM MYRON

Symphony No. 2

Violin Concerto No. 2

Viola Concerto

The Soldier's Return (String Quartet No. 2)

Katahdin (Greatest Mountain)

Contact featuring David Darling

Mille Cherubini in Coro featuring Lee Velta

This Day featuring Andy Voelker

|

|

|

|

|

Monday, August 07, 2006

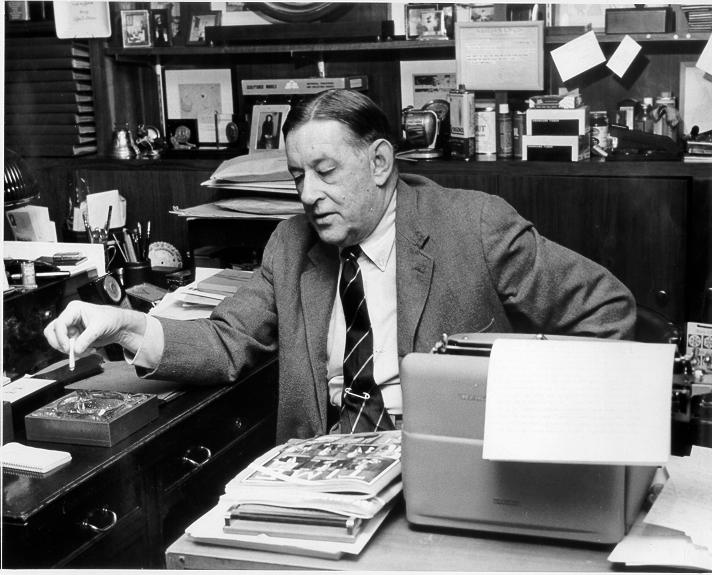

An Artist is His Own Fault

"The rich appear to him most representative of the human condition, because their lives are frankly, clearly, and fully implicated in the life of society."

Norman Podhoretz on John O'Hara

Of course, following the Great crash, and in the first frost of the great depression, and with Europe unravelling like a cheap suit, our countries most serious critics had put on their long faces and were impatient with the complaints of fictional characters whose bellies were full and dwellings sited lakeside, adjacent to the fairway, or overlooking Central Park; to be sent packing by the upper middle class to the lower middle didn't seem then a decline fit for empathy or even curiosity. Let's say that to write a novel of manners was considered politically, thus aesthetically incorrect.

To be serious was to be engaged with the historical rather than the transitory consequences of capitalism, and social Darwinism was too busy in its cruel communal labors to be reproached for clubhouse postings and exclusions. America's official readers were suspicious of the novel of manners even before Henry James's time, and during Edith Wharton's, and F. Scott Fitzgerald's, and John Marquand's. They are suspicious of it now, assuming that "manners" refer to social climbing and that climbing is a fit action only for mountaineers, that slights are life-changing only if suffered by those of a minority religion or with off-white skin pigmentation. Novelists of manners- faced with this humanly comprehensible hostility to the pain of pale-faced, educated, fully employed, or trust-funded characters- must be resigned to critical indifference. Oddly enough, this critical unfriendliness has often been the handmaiden of popular success: Wharton, Fitzgerald (while the Jazz Age was still on), O'Hara, Marquand, Auchincloss.

Even at their most catholic, serious American critics find it difficult to take seriously coded behavior, systems of civility and discrimination, "the rich" and their damned manners and mannerisms.

Geoffrey Wolff

The Art of Burning Bridges: A Life of John O'Hara

2003

posted by Tom Myron

|

| |