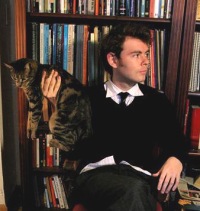

Q&A with Gabriel Kahane

Gabriel Kahane performs Thursday, 9 October with Rob Moose at the Cornelia St. Café (8:00pm, doors; 8:30 Diane Birch, opening; 9:30 Gabe). This week, Gabriel and I exchanged some e-mail Q&A. The conversation got pretty deep. –David Salvage

Gabriel Kahane performs Thursday, 9 October with Rob Moose at the Cornelia St. Café (8:00pm, doors; 8:30 Diane Birch, opening; 9:30 Gabe). This week, Gabriel and I exchanged some e-mail Q&A. The conversation got pretty deep. –David Salvage

DS: Gabriel, I’m enjoying your album [Untitled Debut]. I’m wondering, as I listen, what non-musical sources of inspiration you might have. Like poets, artists, and so on.

GK: I think that’s a great question. There are certainly some fairly explicit literary inspirations for some of the songs on the record. “The Faithful” was written as a kind of response to Claire Messud’s novel “The Emperor’s Children,” which I think very elegantly and devastatingly deals with 9/11. “7 Middagh” was written after reading Sherill Tippins’s glorious book “February House,” which is an account of the artist commune at 7 Middagh Street in Brooklyn Heights during World War II in which W.H. Auden, Carson McCullers, Benjamin Britten, Peter Pears, Gypsy Rose Lee, and Jane and Paul Bowles were charter members. But more generally, I think I’m always looking at art of all mediums to find different approaches to achieve some kind of emotional catharsis. I try to be as emotionally direct as possible in my work without getting sentimental (I hope), and so that tends to be what I seek out in other art.

DS: I’m glad to hear you use the phrase “emotionally direct:” directness is a quality I find refreshing in art (as well as in life). But what the heck does “directness” mean? Does a moment come to mind while composing when you thought the music or lyrics was not direct enough? If so, what did you do?

GK: I think “directness” stands in opposition to the deliberate obfuscation of an emotional impulse. I think many would agree that two hallmark traits of the postmodern era are irony and cynicism, and neither of these particularly lends itself to emotional directness in art. I think what you get in this era is a fear of saying what’s been said before, being labeled “sentimental” (which serves as a catch-all for anything “felt”), and so on. Accordingly, some artists tend to hide behind being obscure as a defense… And I’ve been guilty of that, certainly. Particularly in lyric writing, it’s easy to cop out with things that rely on vague imagery, things that rhyme conveniently but don’t mean anything, etc… I’m being somewhat reductive of course– there are plenty of lyrics that I love that rely on language as music, where you can’t say, “oh, this line means that.” But while there’s a huge amount of value in something being lyrically ambiguous enough to allow for a listener to project a unique meaning onto the text, there has got to be a desire to communicate for that to pan out.

DS: It seems like our capacity as a culture to use communication to hide ourselves only continues to grow… But let me change the subject a little. I want to know what you are getting at on your album with the “Fughetta” and the Bach chorale transcriptions. I have my own ideas, but how about you just take it away?

GK:I don’t think I’m “getting” at anything, necessarily– t least not ideologically, if that’s what you mean. Those three pieces on the record that you’ve mentioned, along with the fourth instrumental interlude, have somewhat pragmatic functions in my view. In the case of the Fughetta: I wrote it on a whim for a gig as an introduction to “Side Streets,” whose melody provides the fugue subject. In sequencing the record, I think I was superficially interested in the outlining of the F major triad at the beginning of the fughetta coming out of the F major cadence at the end of “Slow Down.” (Not the deep response you were looking for??)

In the other two cases, “The Faithful” was written several years ago, and somehow, I had decided to frame it with a reharmonization of a famous old Lutheran melody, one which Bach harmonized more than a dozen times. To put the pseudo-Bach quote in context, I decided to frame the song with an actual chorale harmonization (albeit with weird improvised piano bits added) on one side, and then a kind of deconstruction of the hymn afterward. In the latter case, there was the desire to get from B minor (end of “The Faithful”) to F major (fakeout beginning of “twice in the night”), so I just made a little arrangement accordingly.

DS: Actually, this musical shop talk is neither unexpected nor unwelcome to me. This album shows a high level of technical sophistication. Do you study scores regularly? If so, what are you looking at these days? If not, could you talk a little about a composer or songwriter who’s been especially important to the development and enrichment of your craft?

GK: Thank you for that very kind praise. I wish I could say that I study scores regularly, but the truth is that I’m not quite that sophisticated. It’s something that I definitely would like to do more of. Over the years, I’ve studied a few of the Ligeti piano etudes casually, but not for the sake of performance. I do look at a lot of Mozart piano concerti; I find that music deeply enriching–sonically, spiritually, emotionally.

As for a single influence on my craft, I think the biggest enrichment has come from observing my peers, many of whom have incredibly evolved work ethics. The cultivation of work ethic in the last couple of years has been the biggest change in my life, much more so than anything specifically content-related that I could say about harmony, text, texture, etc. I really believe that the greatest challenge of being a composer is learning how to sit down every day and write, regardless of mood. And I do attribute my gradual development in that department to the good influences and role models around me.