ONCE (during)

Last night, Rackham Auditorium on Washington Street in Ann Arbor, MI became a sort of communal time machine. Complete with a vintage magnetic tape reel, electronic synthesizer and “public disturbance”, performed by students from the University of Michigan School of Music’s Composition Department, the hall carried its occupants back to the revolutionary decade of the 1960s when a group of young, local composers called the ONCE Group started a groundbreaking and historic contemporary music festival. These composers were Roger Reynolds, Robert Ashley, Gordon Mumma, Donald Scavarda (pictured to the right) and the late George Cacioppo, and the music they created for the ONCE festivals was on display last night to reenact the sounds of the original events.

The concert kicked off ONCE. MORE., an interdisciplinary celebration of ONCE and its related cultural period in American history, by presenting over three hours of music by the founding composers. After remarks by the co-directors of the concert series, University of Michigan School of Music Professor of Composition Michael Daugherty and Professor of Performing Arts and Technology Mary Simoni, the music began with Roger Reynolds’ Mosaic (1962) for flute and piano. Notably vibrant in its use of instrumental colors, many of which were produced via extended techniques, Mosaic seemed too introverted to be a concert opener. Nevertheless, University of Michigan Professor of Flute Amy Porter and Professor of Piano Performance John Ellis succeeded to draw me in to a complex musical world wherein the limits of acoustic instrumental sound were well traversed. I was left with the impression that the flute and piano behaved as one sound producing body, yielding an aural landscape that both yearned for and hinted at electronic music.

Next on the program was Robert Ashley’s in memoriam…Crazy Horse (symphony) (1963), which hands an ensemble of 32 players a series of graphic scores and lets them interpret the symbols as they wish. Crazy Horse and its companion piece on the second part of the concert, in memoriam…Esteban Gomez (quartet) (1963) epitomize the experimental and avant-garde sentiments that spawned the original ONCE concerts. As you would expect, these two improvised pieces were very different, but I felt like Crazy Horse was delivered more successfully. Mark Kirschenmann’s Creative Arts Orchestra presented in memoriam…Crazy Horse cohesively, developing specific sound ideas (i.e. verbal/oral noise, sustained tones/harmonies, dense polyphony, etc.) and passing them among the different instrumental forces on stage. In contrast, the University of Michigan’s Digital Music Ensemble’s performance of in memoriam…Esteban Gomez was unfortunately static and I was chagrined by their heavy use of modern sound manipulation technologies. However, it speaks to the flexibility of graphic notation that a piece like in memoriam…Esteban Gomez can be realized so differently at separate points in history and still fulfill the composer’s intention.

The first part of the concert ended with two solo piano pieces: Gordon Mumma’s Large Size Mograph (1962) and Donald Scavarda’s Groups for Piano (1959). Mumma’s piece was one of my favorites of the night because of its extraordinary subtlety. Every phrase was terse and profound, such that, in rehearsal, Mumma coached his pianist, also John Ellis, to squeeze every drop of meaning from each note. Scavarda’s Groups was similar, except that its limited resource was time. Only 55 seconds long, this rigorously constructed experiment in brevity seemed light and witty, which made it a perfect prelude to the first intermission.

in memoriam…Esteban Gomez began the second part of the concert and was followed by Donald Scavarda’s FilmSCORE, a piece for two pianists who improvise in response to a projected film. In Scarvarda’s own words, FilmSCORE arose from his desire, “to find and expand the entire idea of musical notation…[I] photographed any round lights that were self-illuminated…[and] put them out of focus until they became unrecognizable and abstract”. University of Michigan Professors of Composition Michael Daugherty and Kristin Kuster successfully translated their visual stimuli to music, particularly in the area of texture, where they reflected the activity level of Scavarda’s film faithfully. Though there was a strangely anachronistic stretch of pan-diatonicism at one point in the piano part, FilmSCORE felt like a true emblem of the time in which it was created. FilmScore and GREYS (with sounds) (1963), the next piece on the concert and another Scavarda film with electronics by Gordon Mumma, succeded the most at transporting me to the technological and musical environment of the first ONCE festivals.

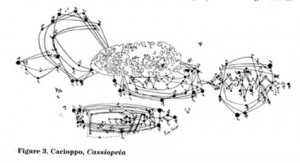

The last two pieces on the second part of the concert were George Cacioppo’s Cassiopeia (1962) for solo piano and Gordon Mumma’s Sinfonia (1958-60) for 12 instruments and magnetic tape. Mumma spoke in place of the late Cacioppo, and explained Cassiopeia’s complicated and bizarre score (shown to the right) as, “an extraordinarily efficient encoding of how the notes move from one to another”. Michael Daugherty performed this piece as well, and delivered an exceptional and coherent interpretation. Among the all the night’s tremendous performers, Michael Daugherty and Mark Kirschenmann’s Creative Arts Orcheatra earned extra admiration from me for deriving such pleasingly organized performances of two scores that were daunting’y vague in opposite ways.

Gordon Mumma took the stage one more time to introduce his Sinfonia, which closed the second part of the concert. Described to possess a, “sound-cinema, or sound theater characteristic”, Sinfonia consisted of four short and extreme movements, which traveled from polyphonic density to pointillism and finally to a closing couplet of electro-acoustic sections, the last of which slowly died away. The mixture of tape and acoustic instruments in 1960 was an impressive innovation, though, by Mumma’s own admission, it is impossible to know who did that first.

The evening’s last two musical offerings were Donald Scavarda’s Matrix for Clarinetist (1962) and Roger Reynolds’ Portrait of Vanzetti (1962-63) for narrator, mixed ensemble and electronics. Matrix is both an experiment in clarinet extended techniques and music notation, as the score is a series of thickly outlined boxes containing gestures and/or instructions. University of Michigan Associate Professor of Clarniet Daniel Gilbert, the soloist, handled the work masterfully, and produced the multiphonics, which lie at the heart of the piece, clearly and evocatively.

Reynolds’ Vanzetti was well worth the wait, and possessed a poignancy not found in many of the other pieces on the program. Reynolds was inspired by his experience studying in Cologne, Germany and sees the work as an indirect political statement against the forces that destroyed much of the city during World War Two. University of Michigan Emeritus Professor of Voice George Shirley was a riveting narrator, whose delivery of the text was deftly wed to Reynolds’ score by the ensemble’s conductor Christopher James Lees. A day later, I am still haunted and moved by Reynolds’ setting of selections from the letters Bartolomeo Vanzetti, one of the two immigrant anarchists who were famously and controversially tried and executed for murder in the 1920s.

As I mentioned at the beginning of this article, Tuesday’s concert was only the beginning of the week’s ONCE. MORE. festival so keep checking back here to read about my thoughts on Thursday’s concert of recent pieces by the ONCE composers and other intervening events including today’s panel discussion with Roger Reynolds, Robert Ashley, Gordon Mumma and Donald Scavarda. Also, find me on twitter to get instant reports on the rehearsals and other happenings this week.

Chirstian Hertzog in response #1 above claims incorrectly that the ONCE Festival LP (by Advance in 1966) of Cacioppo’s CASSOPIEA was a solo piano playing against multi-tracks. That recording was of a live performance by Robert Ashley and myself with two pianos, from a concert on one of our 1964 New Music for Pianos tours.

I also attended this concert and was disappointed in the interpretation of Scarvarda’s “FilmScore” by Daugherty and Ms. Kustler. I didn’t see or hear much interaction between what was going on in the film and what the 2 pianists were doing. It seemed they were just playing away with no reference at all to the film. There were spots where the screen was blank and I would have expected some silence or sustain at those moments, or there were moments where the spots of light were moving in differing references to time, but again no direct reaction from the performers. If you want to just get up and improvise that’s one thing, but if there is a pretense of some sort of organizing principle at least make an effort to follow it.

Same with Daugherty’s interpretation of “Cassiopeia”. Every preview I read of this piece described it as ‘etherial’, but I heard nothing of this in Daugherty’s playing, just some stock ‘licks’ thrown about at random.

I was also disappointed in the fact that I saw very few students there – the audience (which was a good turnout) seemed in large part to be over 50.

I found Ashley’s “In Memoriam…” to have been hypnotic and meditative, and was impressed at how well it translates when played using modern electronics.

@ stephen rush:

What, pray tell, is the “point” of Esteban Gomez? Schumann himself acknowledges that the difference in performance practices is indeed a virtue, and that the composer’s intentions were still fulfilled.

If audience reaction was the intent of the performance, then I feel that the meaning of the festival in its entirety has been lost on you. In general —and this sweeping generalization is taken from my interpretation of the composers’ statements— these composers sought to express their unique artistic visions. The intent was not to please the crowd, and your rejection of Mr. Schumann’s critique on the basis of the audience and the composer being pleased with the performance seems to be based more on an emotional response than a logical one.

Indeed, I find it to be a pity that you so aggressively reject Schumann’s subjective opinion solely on the basis that others were pleased with the performance. Perhaps I am missing a step in your logic, but that in and of itself seems to be missing the point of the review. That Schumann can have a distinctly different interpretation of the performance seems to be precisely the point. That you would have such a staunch defense of the interpretation implies that this interpretation is correct. I think throughout the course of music history, it has been made evident that there is no one right way to interpret music. That this has been lost on you seems to me a much bigger pity.

thanks GS. Thoughtful comments, mostly. Of course, you completely missed the point of Esteban Gomez. Did you miss (totally) the composers ELATION at the performance? Where were you? Did you not care that the audience was SHOUTING in joy after the piece? Has this (audience reaction) lost it’s meaning to you? Pity.

50 or so years later, it can be difficult to perceive how thoroughly original and groundbreaking the ONCE group of composers were. Correct me if I’m wrong, but Donald Scavarda’s Matrix was the first composition anywhere to employ clarinet multiphonics. There wasn’t an electronic music studio at U of M in those days. The electronic pieces of Mumma and Ashley were from their DIY collection of equipment. The graphic scores of Ashley and Cacioppo and the mobile form of Scavarda’s Matrix demonstrate an awareness and acceptance of the New York School and their techniques several years ahead of the rest of the country.

I haven’t looked at Ashley’s “in memoriam” works in years, but doesn’t he specify chains of interactions from performer to performer, which must then be interpreted via the graphic scores?

Interesting to hear that Cassiopeia was interpreted as a solo work. On the old ONCE festival LP, it was done as a pianist playing against multi-tracks. And live versions I heard and/or participated in when I was a student in the 80s were done with multiple keyboards. George Cacioppo would have approved, though.

I look forward to further reports on the festival!