BAM Next Wave Festival: DBR and friends perform a Symphony for the Dance Floor

The BAM Next Wave Festival is upon us right now. There are a ton of exciting things lined up, including what appears to be a thrilling multi-media extravaganza from violinist DBR. Behold: Symphony for the Dance Floor!

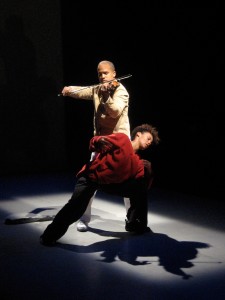

Known for bringing audiences to their feet with sonic collages of classical, pop and hip-hop sounds, DBR ushers the concert hall and dance club into the theater with Symphony for the Dance Floor. In an attempt to homogenize all art forms on one stage, it combines exhilarating music, soulful dance, and photographic artistry, all within a theatrical setting, most notably, in the use of on-stage seating. “Symphony for the Dance Floor speaks to an equality between concert hall and dance club traditions,” explains DBR. “Growing up in South Florida, I went to school, I played in the orchestra, I danced in clubs. It was part of the culture and of the times. So to me, they’re all equal.” Centered around the shrieking, singing, and seduction of DBR’s violin playing, the production is augmented with masterful collaborations including: raw, uncompromising photography and video by Jonathan Mannion (best known for his soul bearing portraits of hip-hop icons Jay-Z, Lauryn Hill, Mos Def and Eminem); choreography by Millicent Johnnie (former resident choreographer of Urban Bush Women); ebullient live dancing; bombastic laptop/turntable soundscapes; emceeing by actor/rapper Lord Jamar (best known for his role on HBO’s Oz); and the direction of D.J. Mendel. “We’ve created a lovely environment for the music, dancing, and audience to all coexist in,” explains DBR. “A composer, a DJ and dancers can have a conversation all under the watchful eye of a photographer. In my world, the last bastion of democracy just might be the concert stage.”

I was lucky enough to ask DBR a few questions about the project:

Symphony for the Dance Floor is a commission from the BAM Next Wave Festival. What did the festival ask you to create, and how do you feel this project contributes to the “next wave” of art to come?

DBR: The festival did not ask me to create anything, specifically, rather I was asked to simply present an idea for a full-evening work. This is the third commission from BAM, and the brilliant and ever-supportive, Joe Melillo, and we have a very gracious and trusting relationship. When I told him my idea for this work, we were both excited by what it could mean for our work, my music, and his audiences. I’m sure how my work contributes to any ideas on art, other than to say, I’m fortunate to have developed a loyal and supportive audience for my work, and a small community of artists to help me develop, perform, and express it.

Symphony for the Dance Floor is about an event during which the concert hall and the dance hall collide. Is there a specific audience you hope the show will reach?

DBR: I think this work is designed for both classical and club audiences. It’s chamber music and chamber dancing. There are wonderful photographs and video installations, and provocative lighting design and costumes. The score is fully reflective of my interests at this time, and include works for violin and electronics, and songs for voice, piano, and violin. I think in today’s climate and ways of communicating, audiences are diverse and highly varied. And they’re also savvy about where they go and what they listen to. My audience, I think, has an age-range of 7-70 years-old, and it seems that many artists have similarly diverse audiences with sophisticated, broad tastes.

This project is about music’s relationship with photography, film, choreography, and lights. All of these things scream Theater! Can you talk a little bit about your love of theatrics?

DBR: I do love the theater, but I wouldn’t label that a love of theatrics. Laurie Anderson’s work has had as much of an influence on my work as The Wooster Group. I spent nearly a decade working closely with Bill T. Jones, and as his Music Director, I was fortunate enough to be privy to his process of creation, much of which is a brilliant use of the theater, well beyond dance and choreographic elements. Tim Fain, the violinist, recently produced a work called Portals, and it’s a stunning work that uses film, dance, and technology in a very sincere, honest, and fluid way. As a musician, I think Tim is a far more accomplished violinist than I am, but as performance artists, we both have something unique and relevant to offer our audiences, in our individual use of technology. In this, more artists will be able to express the depths of their creativity, in more varied and resourceful ways, using technology to give new perspectives on the old ideas of self-expression.

What are the inspirations for the music in this show? Is the music originating more from the classical spectrum or more from the club?

DBR: I don’t really separate or think about music in that way. One of the works in the piece, called Solo, is for solo violin. It was composed as a dance work for the choreographer/dancer Emily Berry. Other than modest amplification, it’s a work that exists on record, on-line, in the dance world, and now in Symphony for the Dance Floor. As a composer, I generally create the best music that I can for the instruments that I have, and then decide the context of their presentation. Nico Muhly raised the many problems associated with using recorded works by orchestras and other large ensembles, and he was right in that, generally speaking, as an industry, we are limiting the scope and reach of our work as composers by not allowing a more full use of those, dreaded, “archival recordings”. I had hoped to be able to include actual samples of my orchestra work in this piece, but alas, I couldn’t get the licenses for their use. We are in talks to have the Symphony for the Dance Floor score transcribed for performances with chamber orchestras, and I’ll be re-imagining some of the purely electronic works for acoustic instruments. There are so many artists and ensembles doing this, it’s become common-hand for the work of composers. But there’s an entire new field of work waiting for composers where we can use recordings of our music in performance.

Going to a concert is generally about sitting and being entertained. This project, however, is about music that “wants to dance” and “wants to move.” Do you want the audience to be enraptured from their seats or do you want them to feel so inspired they get up and dance?

DBR: Well, some of the concerts I go to don’t have seats! But I understand your point. We have audiences sitting on the stage, and some of them have begun to dance [with me!] during the show. We had a technical glitch in Arizona, and in having to buy some time for the crew to fix it, I invited anyone to dance on stage with me. A young woman took of her shoes, and started a duet with me, that quickly grew to a trio when her friend decided to join us. They weren’t professional dancers, just dedicated members of the audience that night. And we danced, and we danced for everyone there as they fixed that glitch. It was only a few minutes, but in many ways, that moment was emblematic of what I’m wanting to achieve in this work. That the dance floor, the concert hall, becomes the last bastion of democracy where all of us, composers, dancers, and audience, are all equal, are all seen and heard, and share in a moment of grace, humility, and humanity. I’d like the audience to determine whatever it is they need to feel. Just feel something. I remind myself to just feel something everyday.

Check it out and get your groove on!