There’s yet another new music series here in San Diego: Connections Chamber Music. I reported earlier this year on their concert featuring Reich, John Adams, Daugherty, and Matthew Tommasini (the series director). For their last concert, they programmed the Quartet for the End of Time. Before I went to the concert, I marvelled at how I’ve heard the Quartet more frequently than plenty of 19th century chamber works just as great such as Beethoven’s op. 132. And–well, read my thoughts and review of the concert here.

Jason Robert Brown, composer of Parade and lots of other excellent musical theater music, has a valuable post on his blog today about his attempts to persuade internet “traders” from illegally offering his sheet music for download for free. Brown joined one of the peer-to-peer communities that had a lot of his work listed and contacted about 400 users, politely asking them to stop offering his material. Most complied, some had no idea what he was talking about, and a few resisted. The issue of who benefits and who loses from the widespread distribution of his work is raised in a lengthy exchange he had with a teenage girl named Brenna…ur, Eleanor… which provides some insights into both perspectives of the copyright debate.

Jason Robert Brown, composer of Parade and lots of other excellent musical theater music, has a valuable post on his blog today about his attempts to persuade internet “traders” from illegally offering his sheet music for download for free. Brown joined one of the peer-to-peer communities that had a lot of his work listed and contacted about 400 users, politely asking them to stop offering his material. Most complied, some had no idea what he was talking about, and a few resisted. The issue of who benefits and who loses from the widespread distribution of his work is raised in a lengthy exchange he had with a teenage girl named Brenna…ur, Eleanor… which provides some insights into both perspectives of the copyright debate.

I know a lot of composers who are pleased to allow people to download their music free and distribute it to whomever they like because they believe doing so provides exposure to their work and grows their “brand” (to use an overused marketing term). Others believe their music is their intellectual property and they should be paid for any use. Where you stand seems to depend upon how commercially “successful” you are. If you’re relatively unknown and there is little demand for your music, giving it away is a great strategy. If there is a market demand for your work in various forms, it’s not.

Who has thoughts on this topic?

I just got off the phone with a reporter from the Chicago Reader, who read our February 12th coverage of Eighth Blackbird’s Composition Competition (on Twitter, this came to be known as the “8Bb boo-boo” post).

In the initial post, I’d expressed my disappointment at finding out that Eighth Blackbird, an ensemble for whom I had a great deal of respect as new music performers, was charging a $50 entry fee for their competition. As the post’s title indicated, it seemed apparent that the competition’s prize would easily be self-funded by application fees, with plenty left over.

We had a lot of comments on the post. This discussion revealed a wide range of viewpoints on the subject, both pro and con. Some posters pointed out that instrumentalists are routinely required to pay robust fees for auditions; why should composers? Others suggested that the ensemble was right in charging a fee, as they would be spending time adjudicating the contest and deserved compensation for that time. But others agreed with me that self-funded commissions are a problematic aspect of far too many composition competitions.

The variance of opinion didn’t hew to a composer vs. performer divide; one of Sequenza 21’s regular contributors, composer Lawrence Dillon, mounted a vigorous defense for the competition’s guidelines. Dennis Bathory-Kitsz, on the other hand, went even further than I did in strenuously rebutting the idea of high application fees and self-funded commissions.

Shortly after our post, and commentary elsewhere on the web, Eighth Blackbird announced that they were postponing the competition to rethink and revise its guidelines. They have recently announced a new competition. Partnering with the American Composers Forum and MakeMusic, Eighth Blackbird will undertake the Finale® National Composition Contest. You can read the competition’s guidelines here.

As I pointed out in my interview with the Reader (the article will run next Thursday, if you’d like to see what they make of it), the Finale competition improves on the previous contest in several ways. Some highlights:

-Each contestant may send up to three works, composed in the last five years, that demonstrate how they would write for Eighth Blackbird. One may include CDs, DVDs, and scores.

– There’s no more application fee; composers may pay a nominal amount ($5) if they’d like for their materials to be returned. Like all good competitions, it remains anonymous. There are no age restrictions.

– Three finalists will each receive $1000 and a $500 travel stipend. They will workshop the piece for a weekend with Eighth Blackbird. The winner will receive $2000 and a performance by 8Bb.

-None of the prizes is a king’s ransom; but paying finalists a travel stipend and giving them the opportunity to workshop their piece with the ensemble are significant opportunities not afforded by many competitions.

I think that this competition will better serve both emerging composers and the ensemble. By partnering with Finale and ACF, 8Bb has high-profile sponsors who are helping to offset some of the administrative costs that were previously passed along to composers. The affiliation with Finale will doubtless garner more attention and publicity for the competition. I’d imagine it will also help to get the word out to a wider and more diverse pool of emerging composers.

I, for one, am pleased that our discussion about composition competitions on Sequenza 21 seems to have made a positive impact. I’m also glad to be able to thank Eighth Blackbird publicly for being receptive to criticism and open to discussion. Their willingness to listen to what composers have to say – and then act on it- is another brand of advocacy that’s all too rare and greatly appreciated.

The deadline is September 15th, so get writing!

Staying in NYC this 4th of July holiday weekend? Then come partake of some musical fireworks and pan-patriotic pride as vocalist extraordinaire Phillip Cheah (his vocal range could well classify him as “soprano/baritone”) and pianist Trudy Chan serve up American Dim Sum – A celebration of the American song.

Staying in NYC this 4th of July holiday weekend? Then come partake of some musical fireworks and pan-patriotic pride as vocalist extraordinaire Phillip Cheah (his vocal range could well classify him as “soprano/baritone”) and pianist Trudy Chan serve up American Dim Sum – A celebration of the American song.

The carts will be full of dishes of American fare: beloved songs by Ned Rorem, Samuel Barber, Dominick Argento, Aaron Copland, Amy Beach, and Jack Beeson, as well as exotic delicasies by John Cage (The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs), Henry Cowell (Three Anti-Modernist Songs, written during his incarceration at San Quentin), Milton Babbitt (songs from a never-produced Broadway musical, Fabulous Voyage), and Nicolas Slonimsky (early pieces rediscovered at the Library of Congress with the help of his daughter, Electra Yourke). Topping off the festivities will be a belated, 28-years-in-the-making world premiere of songs from the nurturing river by the the friendliest iconoclastic enfant terrible around, Frank J. Oteri.

It’s all going down Saturday, July 3rd, 7:00 PM, at the Church of St Luke in the Fields (487 Hudson Street @ Grove). Only $10 to stuff yourself silly, so bring a hungry ear or two.

Amos Elkana was one of the composers I found/heard/met almost a decade ago on the original grand experiment in social music-sharing, MP3.com. With an obsidian-like hardness, sheen and edge, his compositions grabbed me then and continue to do so now. Born in the U.S. but raised in Israel, then off to Europe and back to the U.S. to study, Amos pulls together strands of all these places, looking for where the roots tangle and grow together. But the other “root” I didn’t know about then was that Amos’ musical interests had started with jazz and guitar. It was only after coming to study jazz at the Berklee College that his course got redirected into composition.

Amos Elkana was one of the composers I found/heard/met almost a decade ago on the original grand experiment in social music-sharing, MP3.com. With an obsidian-like hardness, sheen and edge, his compositions grabbed me then and continue to do so now. Born in the U.S. but raised in Israel, then off to Europe and back to the U.S. to study, Amos pulls together strands of all these places, looking for where the roots tangle and grow together. But the other “root” I didn’t know about then was that Amos’ musical interests had started with jazz and guitar. It was only after coming to study jazz at the Berklee College that his course got redirected into composition.

Coming over to study at the same time was Amos’ long-time friend and musical partner, drummer/pianist Yaaki Levy. Yaaki had a similar career bouncing between Israel and the U.S., and though their paths diverged a bit over the years their friendship never did. Finally last year saw them able to hook up again musically, exploring improvisation as the duo Concoct Sonance. Together their experiences create a music with a real richness, depth and poise; these may be improvisations, but there’s a strong feeling of that composerly sense of a “piece”, not simply an event or string of events.

The duo has been gigging fairly regularly around Europe and Israel, and now they’ve come to NYC for a few concerts these next couple weeks: Friday July 2nd, 7:30pm they’ll be at The Tank (354 W. 45th Street between 8th and 9th); Wednesday July 7th, 9pm they’re playing Puppets Jazz Bar in Brooklyn (481 5th Ave); and Tuesday July 13th, 11:30 pm they’ll be found at Goodbye Blue Monday (1087 Broadway, Brooklyn).

The duo has been gigging fairly regularly around Europe and Israel, and now they’ve come to NYC for a few concerts these next couple weeks: Friday July 2nd, 7:30pm they’ll be at The Tank (354 W. 45th Street between 8th and 9th); Wednesday July 7th, 9pm they’re playing Puppets Jazz Bar in Brooklyn (481 5th Ave); and Tuesday July 13th, 11:30 pm they’ll be found at Goodbye Blue Monday (1087 Broadway, Brooklyn).

I asked Amos to give a little background in his own words, and I pass them along here:

Yaaki and I both grew up in Jerusalem. We met back in high school through mutual friends and we have been making music together ever since. In 1987 we came together to the US to study at Berklee College in Boston. Yaaki as a drummer and I as a Guitar player. I later went on to study composition at NEC and in 1990 moved to Paris for a couple of years before returning to Israel in 1992. Yaaki left Boston after three years for New York and returned to Israel in 1994. About 10 years ago he moved back to New York and has been living there since.

In the past 20 years, Yaaki has been playing drums with other people while concentrating on piano playing and composing for himself. Meanwhile, I have been occupied mainly by composing music for other people and playing guitar for myself. Yaaki, being a wonderful drummer, has been touring the world with singers and bands while developing his piano playing and composition skills on his own. I on the other hand kept playing the guitar on my own while composing and traveling around the world for the premieres of my own compositions. We always wanted to find time to play together as we did in the past, when we both used to live in the same place. Then an opportunity to do so presented itself last January when I came to New York. We went into the recording studio without knowing what we are going to play. The only thing we decided is not decide about anything! We don’t compose, arrange, rehearse or even talk about what we are going to play. We don’t even decide what instruments we will play and how. Our motto is Here and Now. This is total free improvisation. In the studio we just hit the record button and started to play with the instruments that we had around us. Some of the things we played on were not even instruments but noise makers of sorts.

What was so fantastic is that we immediately started communicating as if on the same exact wave length… We didn’t even have to listen to the recording because we felt such exhilaration after the sessions. There may be several reasons why this works, among them an intimate knowledge of one another as best friends for almost 30 years, common likes and dislikes in music and life, maybe even telepathic communication. We don’t know. But the fact is that we get amazing responses to our performances from audience members. Some say they feel as if we are one. Many say that they felt it hard to resist joining us in some way. Some say our music touches them in such a deep level that they cried most of the time… (Imagine, improvised contemporary experimental music having such an effect!). At the bottom line, I think we allow ourselves to have fun and have complete freedom. Not restricting ourselves to any genre or form. This approach works anywhere. Wether we play in Tel Aviv, New York or Berlin.

Right now we have about 30 to 40 recorded pieces. It is tempting to choose some of them and put them on a CD but on the other hand documenting freely improvised music that will never repeat itself… I don’t know… Maybe the approach should be just to perform as much as we can and have people attend the concerts instead of buying CD’s… Yet in order to get more gigs we need to put out a demo at least. The three performances we just did in Tel Aviv were recorded and I am going to upload those recordings to our web site very soon. One of the performances was also videotaped. Your comment about really hearing the “composer” in our approach is very interesting. It probably comes with the territory of being composers for such a long time… In 1989 when I applied for the Jazz department in NEC, I decided, instead of sending them a tape of me playing Jazz standards, to record an improvisation with Yaaki and to send that instead. The response I got from them is that they are willing to accept me and to even give me a big scholarship too but only for the composition department and not the Jazz department… This is one of the reasons why I became a composer.

Not a short order in a Greek coffee shop but the first American open-air performance of Iannis Xenakis’ Persephassa (1969), a thunderous work for six percussionists, including founding member of the Bang on a Can All-Stars Steven Schick and former So Percussion-ist Doug Perkins. The musicians were situated around the Boating Lake in Central Park, with the audience members in the center – in rowboats. Q2, the Internet’s best new classical station, asked its audience to document the event which resulted in a slide show here and a nearly complete video from Liubo Borissov:

persephassa on the lake from liubo on Vimeo.

Putting a musical program together is always a challenge, but it’s one thing on paper, and another live, in front of people. The San Francisco Composers Chamber Orchestra’s Silence of the Wolves program, which it performed a couple of weeks ago at San Francisco’s Old First Church was a curious one. Was it about wolf tones, or the devil’s interval–the tritone –which has more or less been the foundation of modern music since Schoenberg and his school began to exploit it? Or was it about the West, and San Francisco’s being on the wild edge of the continent, which its music director and co-founder composer Mark Alburger implied in his opening remarks from the stage? It seemed to be vaguely and particularly about all these things, and its contents varied considerably in tone, content, and impact. But thankfully no one was thrown to the wolves.

Putting a musical program together is always a challenge, but it’s one thing on paper, and another live, in front of people. The San Francisco Composers Chamber Orchestra’s Silence of the Wolves program, which it performed a couple of weeks ago at San Francisco’s Old First Church was a curious one. Was it about wolf tones, or the devil’s interval–the tritone –which has more or less been the foundation of modern music since Schoenberg and his school began to exploit it? Or was it about the West, and San Francisco’s being on the wild edge of the continent, which its music director and co-founder composer Mark Alburger implied in his opening remarks from the stage? It seemed to be vaguely and particularly about all these things, and its contents varied considerably in tone, content, and impact. But thankfully no one was thrown to the wolves.

Loren Jones’ Wolf Wood, which he described as ” a solo piano piece inspired by the music of Eastern Europe, ” sounded to these ears like one of Satie’s evocative miniatures, especially in its opening, which was followed by lush yet still transparent variations , which Jones, on piano, played movingly. John Beeman’s 2 movement Fancy Free , with the composer on double bass, was carefully written and expressive; its most striking sound image being a sequence of unison rising fourths near the very end.

But what was one to make of Cindy Collins’ Kinesthesia which she described from the aisle — there were no program notes –as being about physical states of mind she’d felt? There’s nothing wrong with musical autobiography if the piece justifies it, but Collins ‘ didn’t seem to. We’ve all had vague or unfocused moments but these don’t necessarily make for an absorbing experience when made into music. Collins did however produce at least one arresting image — a viola/cello drone, played with great concentration by Nansamba Ssensalo and Areilla Hyman, which slowly changed pitch, and evoked an acute sense of disquiet. Davide Verotta’s An Enticement of Silence, which began like an off pitch version of Ives’ 1906 The Unanswered Question, progressed into a series of reasonably varied harmonies and textures, but didn’t add up to much more than that. Our sense of our postmodern world as a chaotic place has produced some provocative music –John Zorn’s comes to mind–but Verotta unfortunately failed to make

anything as powerful, or succinct as his.

Lisa Scola Prosek’s Three Songs from her new opera Ten Days, Dieci Giorni, based on Bocaccio’s Decameron was, as so often with this composer, full of surprises. Transparently scored, clearly played, and vividly sung in English and Italian by soprano Shauna Fallihee, it said what it had to, then stopped . And the 16 person band — the largest complement of the evening — was obviously moved in several places. Conductor Martha Stoddard’s Cowgirl Rondo (with Stoddard sporting a Western handkerchief around her neck) for string quartet and double bass), was vigorous and fresh, though top honors in that department went to Darius Milhaud’s Chamber Symphonies #1 – # 3 ( 1917-22 ) whose polytonal moments barely disguised their very French folk-like structures.

The playing throughout –under Martha Stoddard and John Kendall Bailey–seemed both accurate and enthusiastic, though the more obviously complex pieces by Collins and Verotta suffered from Old First’s unforgiving acoustics — the walls are concrete, the outside brick. Maybe a an orchestra friendly adjustable partition behind the players would help?

Who’s the first (ahem) “downtown contemporary classical ensemble” to be added to the videogame Rock Band?

Bang on a Can All Stars host their annual Marathon this Sunday (6/26) at the World Financial Center Winter Garden in Manhattan from noon-midnight.

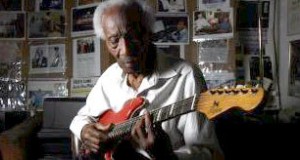

Photo of The Ink Spots Museum by Chris Becker

Being a recent transplant to Houston, Texas, I am only just beginning to take in the breadth and variety of the city’s cultural scene– especially its music. Each dispatch I bring to you from Houston will focus on contemporary composition, improvised idioms, and performances that integrate theatre, the visual arts, and/or dance. Inevitably, my love for rock, folk, blues, jazz, country, zydeco, and all out noise will creep into future writing, the overall goal being to expand peoples’ perception (including my own) of where one can find innovative forward-thinking music.

There may be a connection between Houston’s (lack of) zoning laws and the way that the past, present, and future inform each other throughout its landscape. Maybe that sounds like a cliche. But, if you’ve ever ridden the Houston’s Metro 80 bus through the Third Ward up Dowling Street, past Emancipation Park, and – just before turning left at Sparkle’s Burger Spot toward the glass cathedrals of downtown – observed an unfenced horse enjoying some grass in someone’s front yard, you know that I’m not talking some tourist board hogwash. There are many “zones” throughout this city dedicated to celebrating its history and nurturing its creative spirit. And they sometimes seem to appear out of nowhere.

The Ink Spots Museum (located in Houston Heights) is dedicated to archiving and celebrating the life and work of Texas born guitarist, singer, and educator Huey Long. The museum’s curator Anita Long (Huey’s daughter) welcomed my wife and I for a visit earlier this month and like many Houstonians I’ve met since our relocation from New York City, she was generous with her knowledge of Houston’s cultural scene. Every musician I know would take great comfort in knowing that a family member like Anita would take care of their legacy after they were gone. The museum and its accompanying website (featuring plenty of photos, audio, and video) serves to remind people that the history of American music includes the collective participation of many, many artists each committed to their respective craft. Which is one way of saying you might know that Huey Long was a member of The Ink Spots (from 1944 to 1946 with Bill Kenny as their leader), but not know he also played guitar in ensembles that included Dizzy Gillespie, Earl Father Hines, Sarah Vaughn, Charlie Parker, Fats Navarro, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, and many other luminaries of 20th century jazz and popular music.

Huey Long (who lived to be 105!) was born in 1904 in Sealy, Texas. For the people in Sealy as well as on the farms in surrounding areas, music was a vital part of a day-to-day dominated by hard labor (by the time he was a teenager, Huey was working as a sharecropper). Describing those formative years in Sealy in his pictorial autobiography The Huey Long Story, Huey recalls the names of no less than four different pianists (including his brother Sammy) playing “rags” on the pianos in people’s homes. “Ragtime” was indeed heard in Texas in the early 1900s as was what would become known as “the blues.” Huey’s sister Willie – also a pianist -studied music in Houston, at Wiley College, and brought back to Sealy classical and popular sheet music to play note for note when “grown ups” were in the house and improvise off of when the youngsters were on their own (some parents considered improvisation to be almost sinful behavior).

In addition to classical, popular, and ragtime music for piano, Huey was exposed to the up-tempo groove oriented music (my description) played on guitar at all night “suppers” (which included plenty of dancing, eating, and gambling on the various new betting sites) as well as its more somber and “sorrowful” counterpart known as “slow blues.” Huey began playing both guitar and piano, eventually moving to ukulele – a very popular instrument at the time. After setting out on his own at the age of fifteen and relocating in Houston, he began playing banjo (tuning it like a ukulele but an octave lower) and joined the Frank Davis Louisiana Jazz Band. This was a popular and well-respected band in its time, that played for both whites and blacks in Houston’s segregated communities. He would begin playing guitar after relocating from Houston to Chicago and joining Texas Guinan’s Cuban Band (who traveled to Chicago from New York City to play the 1933 World’s Fair). Later, Huey would join Fletcher Henderson’s Band and Earl “Father” Hines’ All Star Band (I apologize for skipping ahead a bit, and neglecting a lot of formative music making…)

Fast forwarding a bit…

Two sessions Huey did around 1946 with trumpeter Fats Navarro, tenor saxophonist Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, pianist Al Haig, bassist Gene Ramey, and drummer Denzil Best were released on two separate records: In The Beginning…Bebop (which is a compilation of sessions by three different bands) and of Fats Navarro’s recording Nostalgia. These recordings feature some truly kick ass guitar playing from Huey who definitely holds his own in the company of two phenomenally creative horn players. The rhythmic interplay between guitar and piano (and bass and drums…) is incredibly funky. This is bebop (probably) inspired by the music heard at Sealy’s all night suppers: Danceable, unpredictable, and filled with sly humor.

Teaching and composing music – including several chord melody solos based on themes from European Classical repertoire – would be a major part of Huey’s life along with researching his family tree creating an exhibit of his life’s work that would become The Ink Spots Museum. Anita talked to us about the possibility of the museum one day becoming a virtual exhibit – and there is plenty of history and music from Huey’s life as well as from Texas that should be shared with the world. For now, in addition to the website, there is this small museum – a standing structure in the midst of Houston’s un-zoned landscape – that you can make an appointment to visit.