Black American composers dominated the programming at two of New York City’s major institutions last week — a 180° turn from the typical fare of Dead White Men at most orchestral concerts.

On Wednesday, October 16, Carnegie Hall presented Sphinx Virtuosi — the flagship ensemble of the Sphinx Organization, an organization whose mission it is to encourage careers of Black and Latino classical musicians and arts administrators. Thursday at Lincoln Center’s Geffen Hall was New York Philharmonic’s program “Exploring Afromodernism” — a program which was repeated on Friday. Both concerts featured outstanding and committed performances of mainly 21st century classical works.

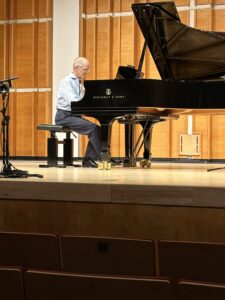

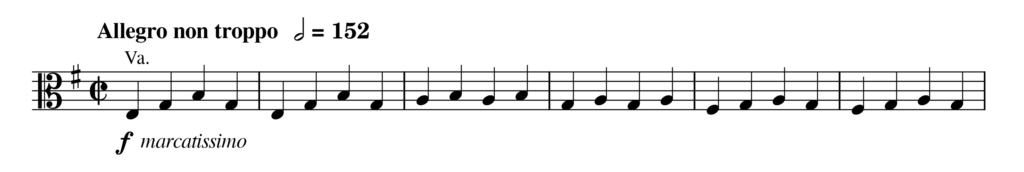

Sphinx Virtuosi is a conductorless chamber orchestra of 18 Black and Latino string players. It can be hard to pull off cohesive performances without a conductor, but it was immediately apparent that this ensemble was up to the task. The concert began with a reworking of Scott Joplin’s overture to his opera Treemonisha, arranged by Jannina Norpoth. The work infused classical gestures with blues, gospel and a bit of ragtime. The most effective and exciting selection was the world premiere of Double Down, Invention No. 1 for Two Violins by Curtis Stewart, performed by Njioma Chinyere Grievous and Tai Murray. It was a brilliant display of virtuosity from both violinists, playing off one another in a keen game of counterpoint which included a fiery display of fiddling as well as percussive foot-stomping. The audience roared its approval with a lengthy standing ovation. Stewart’s other work on the program was the New York premiere of Drill (co-commissioned by Carnegie Hall, Sphinx Virtuosi and New World Symphony). Percussionist Josh Jones, a member of the ensemble, was the soloist. It was a wild piece with frenetic drumming countered by subtle moments of gentle trills on wood blocks. All in all, it was a roiling cluster of excitement.

Music by Derrick Skye, Levi Taylor and the 19th century Venezuelan-American Teresa Careña, rounded out the brief program, which included a five-minute promotional film and comments by Sphinx Organization president Afa Dworkin.

The New York Philharmonic’s program was a wonderful display of a range of talents and generations conducted by Thomas Wilkins. It began with Carlos Simon’s Four Black American Dances, which impressed right away with the composer’s great orchestration. The rich first movement showcased the brilliant playing of every section of the Philharmonic, including a rollicking solo by concertmaster Sheryl Staples, who showed off her great artistry later in the work as well. After a somewhat schmaltzy second movement (“Waltz”) and predictably percussive third (“Tap!”), the final section (“Holy Dance”) began with a mystical aura which devolved into a loud and jaunty display.

The New York premiere of Nathalie Joachim’s concerto Had To Be, written for the cellist Seth Parker Woods began with an off-stage band replicating a New Orleans-style “second line.” After a smooth transition into a slow and lush passage by the orchestra on stage, the solo cellist had a lyrical soulful melody. The second movement, “Flare” launched with boisterous brass and percussion, which tended to drown out the strings. “With Grace,” the final movement, was beautifully emotional. Though the soloist wasn’t given an especially virtuosic part, Woods’ stage presence dominated throughout the work. Wilkins graceful conducting infused an appropriate amount of emotion into the performance.

David Baker’s Kosbro was intense from its very beginning, with driving rhythms, insistent timpani whacks, double-tongued brass and winds and angular melodies. Written in the 1970s, the work was an effective combination of jazz and classical styles.

William Grant Still’s gift for melody, harmony and orchestration made me wonder why this particular work – Symphony No. 4, Autochthonous, (the subtitle refers to indigenous people) isn’t programmed more often. Still’s superb orchestra writing balanced winds and strings in a dialogue which Wilkins navigated beautifully, each exchange infused with profound meaning.

Beyond the demographics of the composers, a similarity on both of these programs was that each of the works by the living composers was an olio of styles. In each case, the creators sought to include a variety of folk, pop, jazz and other cultural idioms in a single composition. It may be unfair to generalize, because the selections were undoubtedly programmatic decisions. I promise not to make a broad generalization until I hear more music from each of these composers, which I am eager to do.

With regard to the focus of these two concerts, I am going to say something very unpopular: Nobody is proclaiming that there aren’t enough White rappers or that Anglos aren’t well enough represented in, say, Latin jazz or conjunto music. And yet in recent years there has been great emphasis on striving for diversity in classical music. I’m not saying we shouldn’t work very hard to be inclusive of all Americans — or of all peoples in general for that matter — to be a part of this art form, this culture. I’m wondering aloud why it seems especially crucial in classical music.

Let’s discuss.

Be that as it may, the Sphinx Organization has been a leader in encouraging careers and celebrating people of color in classical music for over 25 years. They have done an admirable — nay amazing — job, welcoming hundreds of young musicians into the art form, creating role models for future generations, and creating an environment in which it is not only comfortable, but encouraging for young musicians to get involved and excel in the field.