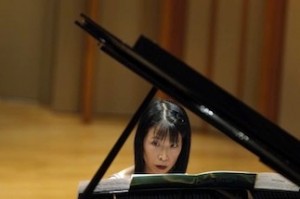

The Soundwaves new music series and Piano Spheres teamed up to present Garlands for Steven Stucky, a concert of piano music performed by Gloria Cheng. Steven Stucky was a long-time composer in residence at the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and his untimely death in 2016 touched his many friends here deeply. Garlands for Steven Stucky is a memorial tribute in the form of a CD album of short piano pieces contributed by no less than 32 students and musical colleagues. Each piece is short – just two or three minutes – and this concert at the Santa Monica Public Library offered a preview prior to a full concert scheduled for Zipper Hall on November 27.

The Soundwaves new music series and Piano Spheres teamed up to present Garlands for Steven Stucky, a concert of piano music performed by Gloria Cheng. Steven Stucky was a long-time composer in residence at the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and his untimely death in 2016 touched his many friends here deeply. Garlands for Steven Stucky is a memorial tribute in the form of a CD album of short piano pieces contributed by no less than 32 students and musical colleagues. Each piece is short – just two or three minutes – and this concert at the Santa Monica Public Library offered a preview prior to a full concert scheduled for Zipper Hall on November 27.

A short video was shown prior to the concert describing Stucky’s academic career and residency at the LA Phil. Esa-Pekka Salonen and Deborah Borda spoke highly of his accomplishments and the warm personal connections he enjoyed with his colleagues. The video also outlined the Steven Stucky Composer Fellowship Fund, intended to help composition students who are just beginning their study. Proceeds from the Garlands for Steven Stucky CD will benefit this fund.

Gloria Cheng then introduced the music of Steven Stucky by way of playing movement 1 of Album Leaves (2002), a series short piano pieces he described as “ … in the nineteenth-century mold of Schumann, Chopin, or Brahms.” This opened with a simple five-note melody that seemed to hang mysteriously in the air, followed by more complex passages that fluttered like a flock of restless birds. A series of darker, enigmatic passages in the lower register added to the magical atmosphere just prior to a quiet ending. This short piece set the tone for the sampler of musical memorials that comprised the balance of the concert.

Two former students of Steven Stucky, now UCLA Music Dept faculty and in attendance, were asked to describe his influence as well as their contributions to the album. Kay Rhie, a student of Stucky while at Cornell, spoke of his generosity, curiosity and wide-ranging interests outside the arts. Ms. Cheng played Rhie’s Interlude, which bore some resemblance to the Album Leaves piece, sharing its subdued and enigmatic character. David S. Lefkowitz described his piece, In Memorium, as a soggetto cavato – or carved signature – using the letters in Steven Stucky’s name to determine the opening notes. This resulted in a simple, declarative melody of strong notes that seemed freighted with sorrow. Complex variations followed in the lower registers, which turned dramatic prior to the repeat of the opening melody, and a quiet fade-out. Both pieces were suffused with veneration and genuine affection.

Esa-Pekka Salonen contributed Iscrizione and this opened with a spare line of single notes that unfolded into more complex passages, tinged with a sense of anguish and loss. A deep rumble in the bottom registers added a sense of sadness, followed by a quietly moving farewell at the finish. Capriccio by Julian Anderson followed, and Ms. Cheng explained that Anderson’s intention was simply to write something that Steven Stucky might have enjoyed. Accordingly, this piece was more optimistic with light, rapid strings of notes that bubbled upward. Skittering sounds followed, both charming and delightful, as if a mouse was scampering about on the keyboard. The dynamics and tempo increased until a dramatic crash of chords at the finish slowly dissipated into the air.

Four other piano pieces were performed by Ms. Cheng to close out the concert. Steven Mackey contributed A Few Things (in memory of Steve), a lighthearted interchange between quick, bright phrases as if holding a conversation with pleasant company. Inscription, by Pierre Jalbert followed with complex and fast passage work, a fond remembrance of the Stucky wit. Judith Weir’s Chorale, for Steve was perhaps the closest to church music, full of airy introspection at the opening and ending with the power and simplicity of a simple hymn. The final piece was Glas by Daniel S. Godfrey, opening with great booming chords that brought to mind cathedral bells, then continuing with a series of quietly thoughtful stretches full of grandeur and grace. Glas was the perfect piece to close out the concert.

Garlands for Steven Stucky is a powerful testimony to the esteem and affection held for Steven Stucky by all those who contributed to this remarkable album. Ms. Cheng has done a great service to organize and flawlessly perform all 32 works for the CD. This preview concert was an opportunity to appreciate how much Steven Stucky has meant to our musical community and how much he will be missed.

Garlands for Steven Stucky is available from Amazon and iTunes.