Hearing Landscapes Hearing Icescapes

Lei Liang

New Focus Recordings

From 2012-2022, composer Lei Liang did a residency at the Qualcomm Institute at UC San Diego, where he is a full professor. At Qualcomm, Liang worked with scientists in a variety of disciplines – software developers, robotic engineers, material scientists, cultural heritage engineers, and oceanographers – to infuse his music with ecological and ethnographic elements. The result, Hearing Landscapes Hearing Icescapes, are two electronic works that incorporate samples, folk songs, and a few live musicians.

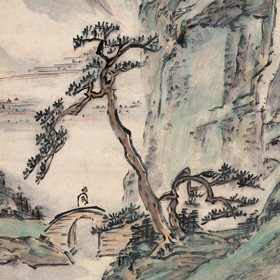

Hearing Landscapes is an homage to Huang Binhong (1865-1955), a gifted landscape painter. The audio components of this electronic score were in part realized by analyzing the types of brushstrokes used by Binbong, and translating them into sound. Visual artists did further analysis of the painting using their own methodologies. There are three samples from 1950s China used successively in each of the piece’s movements: a hu-aer folk song performed by Zhu Zonglu, a renowned singer from northwest Qinghai Province, xingsheng (crosstalk) in the Beijing dialect by comedians Hou Baolin and Guo Qiru, and guqin performer Wu Jin-lüe playing “Water and Mist over Xiaoxiang.” Other sonic devices used by Lei Liang include a “rainstorm” made by dropping styrofoam peanuts in an open piano, and the distorting of spoken voices to create indecipherable “tea house chatter.”

It is fascinating to learn of the roles of many integrated disciplines used to fashion Hear Landscapes. The musical results are compelling. In “High Mountain,” the “strokes” found in the melodic lines, passages of upper partial drones, and the piano storm, ebb and flow and set the stage for Zhu Zonglu’s singing. Movement 2, “Mother Tongue,” a reference to Lei Liang’s own preferred dialect, creates swaths of distressed, unintelligible speech alongside the banter of the two comedians. “Water and Mist” returns to the clarion harmonics and brushed melodies. Dripping water appears alongside Wu Jin-lüe’s elegant playing of the guqin. A passage that incorporates sustained strings follows, succeeded by a lengthy passage of solo guqin and water sound receding until the piece’s conclusion.

Hearing Icescapes uses different source material, including recordings of contemporary performers: David Aguila, trumpet, flutist Teresa Diaz de Cossio, and violinist Myra Hinrichs. Oceanographers provide sounds they had recorded in the nearly inaccessible Chuckchi Sea, north of Alaska. It takes echolocation as a formal design, with one part of the piece indicating the “Call” and the other the “Response” of this phenomenon. Ice, wind, bearded seals, belugas, and bowhead whales create an extraordinary variety of sounds that, without this project, would be available to be heard by few humans. At over twice the duration of Hearing Landscapes, Hearing Icescapes is expansive, the first movement gradually unfolding from the cracking of thin ice to flowing water to an effusive whales’ chorus at its close. Throughout, crescendos and diminuendos of water sounds are accompanied by short whistles from whales. The live instruments are fairly subdued, playing sustained tones underneath the surface of the soundscape.

The second movement begins with snatches of the main source material, a combination of the ice noises and whale song. The live instruments are then foregrounded, imitating the whale sounds in a response to the first movement’s mammalian outcrying. Hinrich uses bow pressure to create an imitation of the ice noises. Aguila is an imaginative interpreter of the more boisterous sounds from “Call,” and de Cossio mimics the whale whistling with considerable fervor. A pause, followed by falling ice, demarcates the movement’s structure. Once again, the whales take up their echolocation, this time in a virtual colloquy with the live instruments. The combined forces end the piece in thrilling fashion.

Artists are often, by necessity, so focused on short term deadlines for projects, that they don’t get to innovate. Lie Liang’s decade spent with his colleagues at Qualcomm Institute has resulted in considerable innovation and two significant works that resonate with cultural studies and ecology, while at the same time providing diverting music. Recommended.

-Christian Carey