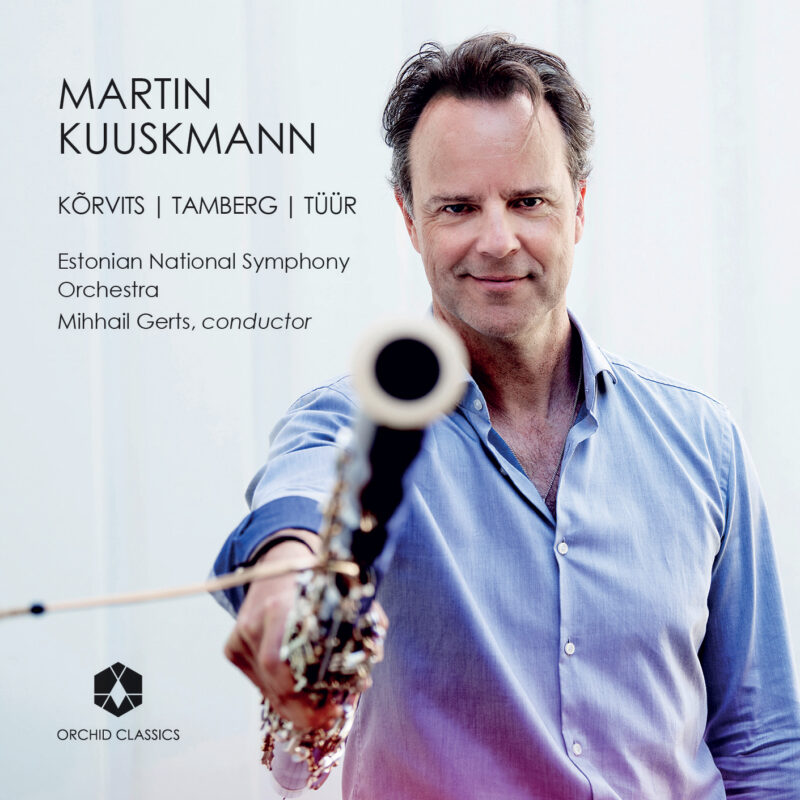

Martin Kuuskmann (b. 1971) is an Estonian born, multi-Grammy nominated virtuoso bassoonist noted for his high energy, charismatic performance style across a wide spectrum of idioms and repertoire. To date, over a dozen concerti have been written expressly for him. In addition to maintaining a busy international recording and concertizing career, he holds the chair of Associate Professor of Bassoon at the University of Denver’s Lamont School of Music. I first became aware of Kuuskmann’s work in 2008, when I heard him perform Luciano Berio’s Sequenza XII for solo Bassoon during a one day festival of the complete Sequenzas held at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater. On that occasion I wrote:

“Martin Kuuskmann’s performance of Sequenza XII for Bassoon left me wondering why that instrument has not long since replaced the electric guitar as the instrument of choice for disaffected teenagers around the globe. Playing from memory and holding his instrument without the aid of a support strap, he laid down a 22-minute industrial pipeline of sliding, distortion-laden multiphonics that gave me the vivid impression of a Jimi Hendrix guitar solo emerging from one of Anselm Kiefer’s collapsed concrete labyrinths.”

Over the ensuing 17 years, that 2008 performance has remained fresh in my memory. In fact, anyone who knows me has probably at some point heard me recount the experience. So, I was especially pleased when Martin himself brought this new CD, containing 3 of the aforementioned 12-plus concerti that have been composed expressly for him, to my attention.

If it can be generally agreed that the portal to 20th (and now 21st) century music first opened in 1913 with Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps, it’s worth recalling that that epoch-making work begins by emerging from silence with an extended, utterly bewitching, unaccompanied bassoon solo. I believe that Stravinsky’s decision to commence in this manner was not mere happenstance. If we think of individual instruments in the way that we think of actors – as dramatis personae in an extended narrative – surely the bassoon represents the complex and unpredictable character actor. Berio himself considered something like this view as essential to the creation of his 1997 bassoon Sequenza. He calls Sequenza XII:

“…a meditation on the circumstance that the bassoon – perhaps more than any other wind instrument – seems to have oppositional characteristics in its personality – differing profiles, differing articulation options, differing characteristics of timbre and dynamics.”

Considered as a group, the works on this CD can be understood as a sequence of three unguided tours traversing through and lingering on striking aspects of the full range of the bassoon’s aforementioned abundant “oppositional characteristics.” In this collection, only Eino Tamberg’s work assumes the time-honored multi-movement, fast-slow-fast formal layout typical of the classical and Romantic eras. But, in this instance, the formula is a springboard rather than a straitjacket.

The program begins with Tõnu Kõrvits’s (b. 1969) “Beyond the Solar Fields” (2004). The work is an unbroken, 17-minute span that, to my ears, contains in its musical DNA a deliberate evocation of the musical, dramatic and folkloric sensibilities that gave rise to Stravinsky’s Le Sacre. The piece is compressed in its time span, but wildly expansive in its perfectly timed deployment of swells and washes of ravishing orchestral color and pseudo-impressionistic harmony. I use the prefix “pseudo” here in its scientific, rather than critical/pejorative sense. Kõrvits’s harmonic language in these passages is derived from 20th and 21st century jazz and pop sources. There is no defaulting to the altered, free floating Debussy-isms of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The resulting sound world is familiar, but entirely fresh, never recycled.

The especially evident in the striking moment at the end of the work where a recording of a woman’s voice singing a type of Estonian folk song called a Helletus emerges from the orchestral soundscape. According to Wikipedia, Helletus is not a specific song but a genre of herding call, a form of communication between shepherds and their cattle. The vocalizations are often “non-lexical”, using sounds rather than words to guide, summon or sooth livestock. The deployment of this strategy as a coda to the work is both haunting and rich in extra-musical associations.

As mentioned earlier, Eino Tamberg (1930 – 2010) constructs his Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra (2001) in the time-honored multi-movement format of the classical and Romantic eras. But in this case, an antiquated convention is deployed in the service of pushing against generic expectations. The piece makes no heroic efforts to resuscitate archaic harmonic formulas or reanimate deadened melodic sensibilities. Of course, this kind of Neo-classical approach sets the stage for an arch species of late 20th century ironic wit and self-awareness. In this regard, Tamberg does not disappoint. Each of the concerto’s four movements are marked with both the classical Italian language terminology for designating mood and tempo AND terse, idiosyncratic translations into English of those same designations:

1. Perpetuo moto (It Won’t Stop) Vivo.

2. Interludio – La danza irrequieto (Restless Dancing). Allegro irrequieto

3. Solo (Alone). Lento

4. Postludio – Perpetuo Moto (It Moves Again). Vivo leggiero

The overall form of the work suggests a circle. Two thematically related outer movements, 1 and 4, frame a pair of inner episodes in movements 2 and 3. Movements 1 and 4 are characterized by manic, flickering streams of notes. They are initiated by the solo bassoon and picked up by wildly varying combinations of instruments from within the orchestra. This high-speed, high-energy music always stays just this side of under control. The effect for the listener is both mesmerizing and thrilling.

During the inner episodes, the action winds down from frenetic, “Restless” dancing to a haunting lament from the bassoon. The 3rd movements long, singing passages are draped in pointillistic necklaces of keyboards and mallet percussion performing hushed, rapid arrangements of the earlier dance music. Tamberg was a late 20th century master, and the agile wit, humor and seriousness displayed in the concerto’s formal strategies is borne out everywhere and abundantly in the wry luminance of the music itself.

The Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra (2003) by Erkki-Sven Tüür (b. 1959) is eccentric in its formal architecture and, in this setting at least, unique in its gestation. The unique gestation consists of the fact that the entire piece is a re-write of Tüür’s 1996 Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, this time with the bassoon as soloist. While the reason for this state of affairs given in the CD’s liner notes by Kuuskmann involves a scheduling conflict, the practice of instrumental transcription has a history as long as music itself.

In overall form, the concerto is cast as a wildly asymmetrical pair of movements. Movement 1 is just under 17 minutes long, Movement 2 is just under 5. The piece begins with an arresting set of gestures. A sequence of chords is orchestrated in a bell-like manner, with one group of instruments providing the sharp attack of the imaginary bell’s clapper, and another the long, sustaining tones and overtones of the bell itself. The soloist emerges out of this resonating atmosphere, first appearing as one of the sustained tones, but gradually becoming animated with moving lines and figuration.

From there the music unfolds in a basically episodic manner. In fact, the concerto is something of a composer’s sketchbook of the ways in which an orchestra might accompany, oppose and/or be dominated by a solo instrumentalist – bassoon or cello. For me, the ultimate sonic impression is of a single 22 minute work with an extended coda beginning just before the 17-minute mark. But, the work’s formal asymmetry notwithstanding, the concerto ends as it began – as a sequence of bell strikes. It’s a compelling strategy which, in this case etches itself into the listener’s memory as a vivid, memorable musical landscape.

– Tom Myron, August 2025