Composer/keyboardist/producer Elodie Lauten creates operas, music for dance and theatre, orchestral, chamber and instrumental music. Not a household name, she is however widely recognized by historians as a leading figure of post-minimalism and a force on the new music scene, with 20 releases on a number of labels.

Composer/keyboardist/producer Elodie Lauten creates operas, music for dance and theatre, orchestral, chamber and instrumental music. Not a household name, she is however widely recognized by historians as a leading figure of post-minimalism and a force on the new music scene, with 20 releases on a number of labels.

Her opera Waking in New York, Portrait of Allen Ginsberg was presented by the New York City Opera (2004 VOX and Friends) in May 2004, after being released on 4Tay, following three well-received productions. OrfReo, a new opera for Baroque ensemble was premiered at Merkin Hall by the Queen's Chamber Band, whose New Music Alive CD (released on Capstone in 2004) includes Lauten's The Architect. The Orfreo CD was released in December 2004 on Studio 21. In September 2004 Lauten was composer-in-residence at Hope College, MI. Lauten's Symphony 2001, was premiered in February 2003 by the SEM Orchestra in New York. In 1999, Lauten's Deus ex Machina Cycle for voices and Baroque ensemble (4Tay) received strong critical acclaim in the US and Europe. Lauten's Variations On The Orange Cycle (Lovely Music, 1998) was included in Chamber Music America's list of 100 best works of the 20th century.

Born in Paris, France, she was classically trained as a pianist since age 7. She received a Master's in composition from New York University where she studied Western composition with Dinu Ghezzo and Indian classical music with Ahkmal Parwez. Daughter of jazz pianist/drummer Errol Parker, she is also a fluent improviser. She became an American citizen in 1984 and has lived in New York since the early seventies

|

|

|

|

|

Sunday, April 30, 2006

Cents on the value

I would like to address a couple of bothersome classical music myths. The first one is perfect pitch. As a child, I remember that when listening to song melodies on the radio, I somehow knew what notes that were being played. Later on, with a little practice, I was able to identify by pitch other elements of the music such as bass lines and other musical lines as long as they could be clearly heard. Thatís what is referred to as Ďperfect pitchí - my reference was a piano tuned in equal temperament, and I didnít know there ever was anything else- it was an unquestionable given. Not until many years later did I discover that pitch is not an absolute concept but a relative one. Whatís perfect about having memorized all the pitches of equal temperament and recognizing them? It is only a certain kind of ear training, and when it comes to other tunings and temperaments and even other reference pitches, which I have experienced, the pitch recognition function evolves, but is not as easy as so-called perfect pitch. For instance, when I am tuned to the earth tone (year cycle) my A is approximately 8 cycles below the equal tempered A that we are accustomed to. So relative pitch is actually more useful in these situations that perfect pitch. And what is so perfect about equal temperament, an architectural construction of equal quantities which is actually less than perfect in terms of natural harmony.

And we come to the second myth, the myth of Bach having either created or promoted equal temperament, a fallacy that many scholars still subscribe to, and is still being taught - I even found it in David Lucas Burgeís excellent ear training programs, but again, these training programs are only valid in equal temperament. The confusion may have originated in the Werckmeister V tuning, which is close to equal, but it is documented that Bach used Werckmeister III which is very different from equal.

What is the value of looking beyond the conventional given? Well, it is like going organic. The artificiality of equal temperament is very much like the additives and chemicals that go into processed foods. Artificiality makes things easier but not necessarily better. For those who have ears, natural tunings are like organic food. The difference can be felt, and furthermore, natural harmony has healing properties as well as natural food.

********************************

Johnny Reinhard told me of his research in early civilizations and their music and the natural properties of harmonic tunings:

JR: Over the years I have begun to notice patterns in the spread of human tuning endeavors. While linguists have searched for a basic language underlying human speech, I have been taken by what might be called an ur-music in the sense that original peoples used just intonation intervals as the basis for their music, and that all other advancements are the result of human manipulations by distinct cultures, and often spread by diffusion.

The Capoid peoples, such as the San (Kung!) of southern Africa, utilize the first seven harmonics of the overtone series in their music. They have the oldest DNA on the planet. The Bata Pygmy sing polytonally in just intonation relations, while emphasizing difference tones. They also use a molimo, or giant trumpet which is made of wood and kept in the tree tops of the Congo. It reputes to give a good rich overtone laden blat at the end of a full day. Indian peoples may similarly celebrate the Om. The whole principle of melodic raga is to transverse the distance between overtone-rich tone. This is best characterized by the tambura playing its ostinato of harmonics for hours.

Then there are the Hoomi singers in Tuva, Mongolia, and Tibet. And ancient Greece. And the island of Sardinia, and in other tiny pockets. From this ur-music perspective, the musical aspects of Europeís Renaissance were only possible due to the reintroduction of just intonation intervals. The just 5/4 major third was introduced by Dutch speaking musicians throughout the Mediterranean and its northern environs. Without it, music would have remained essentially monophonic.

EL: Johnny, the New Yorker called you 'a just intonation zealot'. I find that a bit surprising: expert would be a better term in this day of dumbing of the culture, someone who is still holding high standards of accuracy! I donít consider you a fanatic, and I just want to make it clear at this point that I am not a fanatic either! I recognize the superiority of organic foods, but as I am not always able to afford them. I might compromise and eat the food I get at the corner. And that's why so many of my works are still in equal temperament. I remember, during a production of Orfreo, the violinists objected to a historic tuning such as a Werckmeister or Kirnberger because they said it threw their intonation off (they perform in Broadway shows, which explains the issue). Singers also objected because of the various challenges created by misplaced passagios (except for soprano Meredith Borden who can handle any temperament, tuning, plus rock bands and Gilbert & Sullivan to boot). So what am I to do, when such resistance is encountered? If I had my way, I would tune the instruments much more carefully and creatively.

JR: Where does being a fan and being a fanatic separate? Fanatic implies some kind of loss of adequate mental faculties. Being a fan is more like a supporter, an imbiber, or perhaps a consumer. There is with a fan the ability to say no, for example, free will, and all that. Iím a big fan of listening to Beethoven in Kirnberger when there is a piano, (especially played by Joshua) but would prefer to hear his symphonies in extended sixth-comma meantone. I want to hear J.S. Bach in Werckmeister III tuning, Buxtehude, too. However, this is the result of good information and a developing appetite for rich distinctions in tunings.

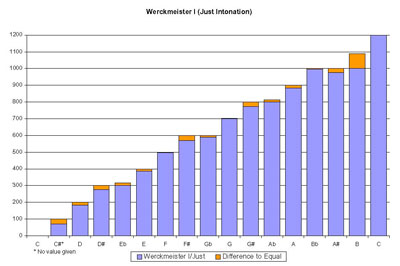

EL: I think the reason why people shy away from microtonality is that it tends to become a form unto itself, whereas it should be part of standard musical training. People really donít know what it's about and microtonality seems so complicated and strange. I plotted some charts to illustrate how Werckmeister I and III and Kirnberger III differ from equal temperament - but this is where the cents on the value become very important, the conventional value being 100 cents for an equal-tempered semitone. The differentials in just intonation are all under 25 cents - a quarter of a semitone, therefore an eighth of a tone. The only real problem is that most trained musicians do not hear these values. They are very slight colorations, just like the differences in light reflected on an object, with sections that are demonstrably darker or lighter. But it does look more three-dimensional with the lights and shadows that make it come alive. Specific training is needed to clearly reproduce these values, but I believe one can become a better musician by doing this, and have good results. However, as an audience member, one doesn't need to receive training in order to enjoy the benefits of a good tuning. The effect will be felt, heard and enjoyed - with complete immediacy.

JR: Kirnberger III was a retro return to Werckmeister III, remaining unpublished for many years after Johann Philipp Kirnberger's death, although it was released to the Bach biographer Forkel in a personal letter by Kirnberger, himself. Only the note A is quite different because it is a full seven cents sharp. However, it is the same sharper A found in Frederick the Great's extended sixth comma meantone court tuning. While ascertaining that any one composer is in any one tuning might seem impossible, if not a waste of time, there is indeed an 800 pound gorilla in the room. Somehow, European reporters failed to explain the advance of sixth comma meantone, even though deaf-mute Saveur wrote in 1700 Paris that sixth comma meantone was the musicianís tuning. That was news to Andreas Werckmeister, who died in 1706. How did it become the new norm, and more importantly, how long did it last? Up through Mahler?The history of music is also the history of notes. Do they need a lawyer to represent them?

EL: They certainly have you on their side! Now, if you aren't all bored with this, you can come and experience the mystery of these alternative tunings with old and new material on Saturday, May 6th. Details follow.

The American Festival of Microtonal Music (AFMM, since 1981), under the direction of Johnny Reinhard, presents a New York City Concert on May 6th at the Church of St. Luke in the Fields (located at 487 Hudson Street at Grove Street). The concert begins at 8 PM and general admission is $15, $10 for seniors and students (with ID) at the door. Saturday, May 6th features pianist Joshua Pierce is joined by a host of winds for Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's PIANO QUINTET in Eb major, and played by renowned Dutch oboist Bram Kreeftmeijer, clarinetist Hideaki Aomori, bassoonist Johnny Reinhard, and hornist Rheagan Osteen, all in Werckmeister III tuning. Similarly tuned are Franz Josef Haydn's LONDON TRIO in D major, featuring flutist Yevgeny Faniuk, Mikhail Glinka's TRIO PATHETIQUE in D minor for clarinet, bassoon, and piano, and Johann Sebastian Bach's DUETTO No. 2 in F major. The winds blow a cappella for Joel Mandelbaum's WIND QUINTET No. 2 in 31-tone equal tempered tuning. John Eaton provides us his new TRIO IN X for flute, oboe, and bassoon.

posted by Elodie Lauten

9:47 PM

| |