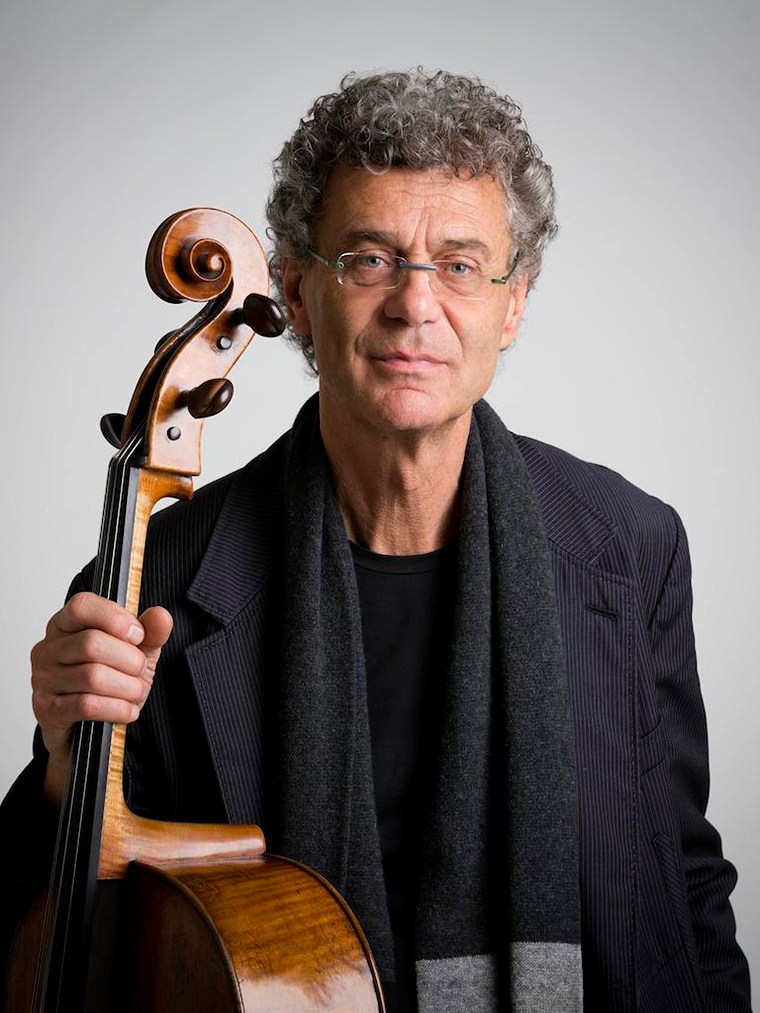

(Photo credit: Ismael Lorenzo)

In the presence of Thomas Demenga, there’s no such thing as a solo concert, for one considers not only the unrepeatable coincidence of performer and instrument but also the composers whose creations bond them. Such fullness of vision was already evident in 1987, when the Swiss cellist began pairing J. S. Bach’s unaccompanied cello suites with contemporary counterparts in a flight of albums for ECM New Series. The first of these viewed the Suite No. 4 through a lens crafted of Heinz Holliger’s chamber pieces, thus setting precedent for a compelling traversal of deciduous and coniferous music. Two composers engaged along the way in the studio—Elliott Carter and Bernd Alois Zimmermann—tangled roots on stage with Bach’s first and third suites for an April 23, 2018 recital at Weill Recital Hall in New York City.

Demenga’s approach to the suites was by turns monochromatic and fiercely colorful. He elicited both suites without a score, Bach’s eternal relevance as ingrained as the striations of the older cello on which he channeled it. He was careful to sand off anticipated peaks and finesse the deeper digs, lest we forget the ways in which Bach’s suites dialogue with themselves, all the while maintaining an underlying spirit of the dance (especially in No. 3’s foot-stomping gigue). In addition to its robust fluidity, his bow was constantly toeing, and at times joyfully crossing, the sul tasto threshold. This allowed natural harmonics and incidental whispers of the strings to bleed through as a veritable sonic fingerprint of the performance. Most impressive was his handling of each allemande, by which he stretched an indestructible suspension bridge from préludeto courante.

Between the pillars of Bach stood the statue of Zimmermann, whose 1960 Sonata for Solo Cello (originally paired with the Suite No. 2 in Demenga’s 1996 album for ECM) was a highlight of the evening—not only for its technical difficulties but also for its sheer musicality. Said difficulties were rendered wondrously in Demenga’s handling. The trembling with which the five-movement sonata opened revealed one mosaic of microtonal transference after another, while deft alternations of pizzicato and arco statements underscored a contrapuntal whimsy. Zimmermann’s score further revealed the same multifaceted understanding of notecraft that Demenga drew out in his Bach interpretations. Carter’s Figment for Solo Cello (1994), a piece written for its performer, likewise opened the concert with a strangely cohesive mélange of lyricism and punctuation. Every gesture was the start of a potential journey. As with much of Carter’s late output, a feeling of inner momentum abounded. Like the arpeggiated etude of Jean-Louis Duport with which Demenga encored, it was a testament to the asymptotic nature of artistic growth.

Such proximities bolded the forward-looking reach of Bach’s music as well as the foundational seeds over which Carter and Zimmermann poured their grateful waters. This reciprocation lent a sense of interconnectedness, of downright genetic heritage, to the sounds, proving that it takes more than a bow and fine muscle memory to extract the beauty therein, but a heart animating it all with genuine love by which each note is released as a messenger into the next continent of time.