Peter Maxwell Davies died about two months ago. I started writing this the week that Max died, but was unable to finish it before now.

Peter Maxwell Davies died about two months ago. I started writing this the week that Max died, but was unable to finish it before now.

I met Max Davies in 1973 at Tanglewood. I had graduated from New England Conservatory in the spring. I had failed to get into any graduate school, which was a sort of minor scandal at NEC. Gunther Schuller was president of the conservatory and also ran Tanglewood, so I got into Tangelwood as the booby prize. Max was the big composer who was there most of the summer. When we met I showed him my music and told him my sad story. Later when I had gone with David Koblitz to see him at the house in Lee where he was staying, he told me with a great deal of urgency, “You need to get out of the country as soon as possible. London is good. You should go to London.” I called my teacher Mac Peyton to see what he thought about that, and he said I should get some guarantee from Max about studying with him if I did go. When I asked Max he said, “I don’t teach, but if it’ll help you you can say you’re studying with me.” So I went. It’s not at all exaggerating things to say that Max changed my life.

Max was at the time thirty-nine years old. Eight Songs for a Mad King had been played for the first time four years before. He had just recently written The Hymn to St. Magnus, which was his first big piece connected to Orkney, which he had only recently moved to (while maintaining, at the time, houses in England). The Devils and The Boyfriend, the movies of Ken Russell for which he had written the music, had both been released two years earlier. I have on the bulletin board next to my computer a snapshot somebody took of Max in the composers’ class. In that picture he has a bushy hair cut and is wearing a white tee shirt and striped pants, he’s standing with his hands turned forward. He might be playing the jester in a production of Taverner, his opera which had been staged at Covent Garden a year earlier. In person he was almost always in motion, almost as though he was a dancer, and his eyes were always flashing.

People often talk about a sort of twelve-tone, or at least modernist, anti-tonal (whatever that means) orthodoxy holding sway at that time in a way that I don’t exactly recognize from my experience, or at least from my memories, but, even so, Max’s willingness to concern himself with and incorporate into his music popular elements like Foxtrots (something very much on his mind and in his conversation at the time) as well as very old elements like isorhythms and plainsong (which he also talked about a lot) was striking and refreshing and seemed very much in contrast to the sort of world view of what music could be and what kind of serious music could be written that I had come to be accustomed to, even at a not very ideological place like NEC. The power and greatness of his music and his musical mind were also inescapable and enthralling.

As it turned out I did do something which amounted to studying with Max. I lived in England for two years, and I saw him about once a month the first year and once every other month the second. A lot of those times I would go to the restored mill that Max had in Dorset and stayed a day or two, during the course of which I would show him what I was writing and get feed back. We also talked a lot, obviously. I can’t imagine the amount of foolishness Max had to listen to, which he treated seriously and with a lot of patience. I also went to lots of rehearsals of his–I remember particularly one where he was conducting St. Thomas Wake with one of the London orchestras at the Cecil Sharp House, very shortly after I was first in London, and a Fires of London rehearsal at the Craxtons’ which was prior to their recording The Hymn to St. Magnus. I also went to lots of performances of Max and the Fires. I went to hear them do The Hymn to St. Magnus at the Aldeburgh festival, not being able to sleep the night before due to excitement. A performance that Colin Davies conducted of Worldes Blisse in the Festival Hall also stands out in my memory.

At the end of the two years I was in England I was a student in Max’s composition class at Dartington Summer School. The course was two weeks; the first week was devoted to analysis. We looked at the Sibelius Seventh Symphony (I was amazed that we were looking at the music of composer who, in my training at NEC, was either ignored or despised) and Max’s Second Taverner Fantasia. Everybody in the class also presented their music, and Max’s comments, which usually included some kind of on the spot compositional exercise that had been prompted by some issue with the piece being presented, were deeply insightful and exciting. The second week of the course The Fires was in residence and each of us wrote a piece that week in which we conducted the Fires. Every night there was a concert, and that year these included the Lindsay Quartet playing Tippett quartets, and the Composers Quartet playing the absolutely brand new Carter Third Quartet, with Carter himself being there. There was also a lot of time in the pub with the other members of the class, including Philip Grange, now one of my best friends, who had just finished high school and who, like me, was there for the first time. The whole experience was thrilling. I was back at Dartington for a number of summers–I can’t remember exactly how many. When William Glock stepped down as director of Dartington, Max became director. He continued teaching, but in a more limited way. One summer there was joint course with Tony Payne, whose wife Jane Manning was also on hand teaching voice classes. That summer Max taught, with Hans Keller, an absolutely thrilling and never to be forgotten analysis class. The first week was on the Mozart G major String Quartet K. 387, the second the Schoenberg Second Quartet. At their concert at end of the first week the Endellion Quartet played the Mozart, and at the end of the second Jane and the Chillingirian Quartet played the Schoenberg. The sense of excitement that built over a week of serious analysis and discussion, mostly by Max and Keller, leading to actually hearing the piece, in each case brilliantly performed, at the end was something that I will never forget. I also still remember vividly insights from both Max and Keller, and moments from the class. One particularly when Hans Keller said that every composer’s first quartet has too many notes, “including yours,” he said to Max, who agreed. One summer there was a joint composers and conductors class with Max and John Carewe, who at the time was conducting the Fires.

I obviously kept in touch with Max aside from Dartington. On election day in 1976, I drove to Poughkeepsie to hear a concert by the Fires on tour. When I saw Max there he told me that he’d just finished an hour long piece called Symphony, a startling development at the time. I went to New York to hear a rehearsal of Stone Litany (for some reason I don’t remember I couldn’t stay for the performance) as part of the New York Philharmonic’s New Romanticism festival, whenever it was. I went to two of the Magnus Festivals in Orkney, (among several visits to Orkney) and heard first performances there of Into the Labyrinth and the Violin Concerto –now the first Violin Concerto–(with Isaac Stern as soloist and Andre Previn conductor–which had the feel of being about the most important thing that had happened in Orkney since the murder of St. Magnus), and a wonderful and hair raising performance by Max and the Royal Philharmonic, I think, of the Beethoven Seventh Symphony, which they had apparently rehearsed for fifteen minutes. Max was also in Boston several times. In 1983 he came for a concert of his music and mine (done several times) on which Mary Sego and I did the first American performances of The Yellow Cake Review, staged by Peter Sellers (Richard Dyer, probably accurately, described my playing as ‘wan,’ and pointed out how gracious Max was to agree to have his music played with mine and that it was to my music’s disadvantage). Max was also the Fromm composer at Harvard one term (I don’t remember the year, but I do remember that he came almost immediately after the first performance of the Third Symphony), and he was also in Boston several years later to conduct the Boston Symphony in his Second Strathcylde Concerto and works of Mozart. The last time he was in Boston was for the NEC Preparatory School Contemporary Music Festival in which he was the featured composer. On one of the concerts he conducted students in his Renaissance Scottish Dances. He told me after that concert that he decided he wouldn’t do any conducting at all after that. Whether or not that was actually the last time he conducted I can’t be sure.

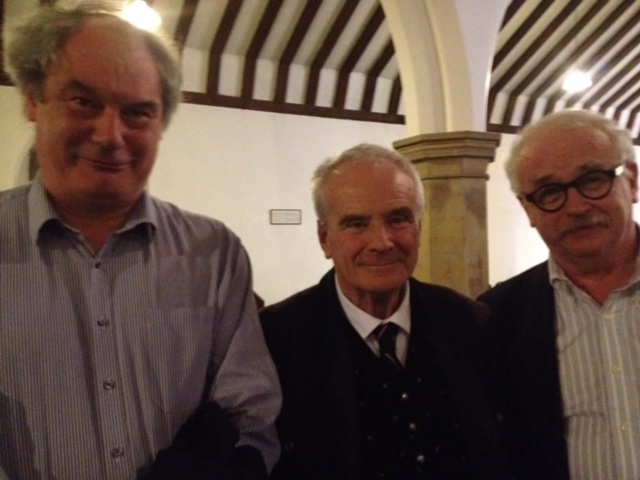

The last time I saw Max was at a concert in a church in Yorkshire, part of the North York Moors Chamber Music Festival in August of 2014. The concert, which was quite long, included Max’s Sixth Naxos Quartet. It was Max’s 80th birthday year, and I had seen him several time in London around Proms concerts which had pieces of his. Max had been very seriously ill with leukemia not too long before that, but he seemed quite healthy and, at that concert, very rested and very happy with the performance of his quartet. That happy memory is commemorated by a photo of Max, Philip Grange, and me taken after the concert.