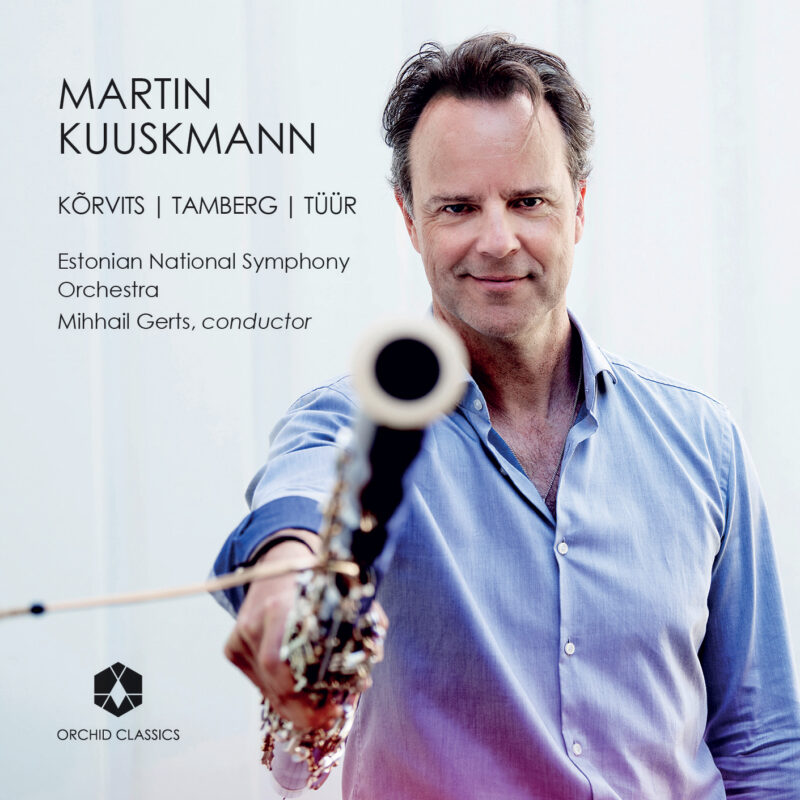

Martin Kuuskmann performs works for Bassoon and Orchestra composed by Tõnu Kõrvits, Eino Tamberg and Erkki-Sven Tüür, with the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra conducted by Mihhail Gerts on Orchid Classics ORC 100384 ©2025 by Orchid Music Ltd. Martin Kuuskmann (b. 1971) is an Estonian born, multi-Grammy nominated virtuoso bassoonist noted for his high energy, charismatic performance style across a wide spectrum of idioms and repertoire. To date, over a dozen concerti have been written expressly for him. In addition to maintaining a busy international recording and concertizing career, he holds the chair of Associate Professor of Bassoon at the University

Read moreDave Seidel has released Intercosmic, a new album of electronic music featuring tracks recorded in studio and in a live performance at The Wire Factory in Lowell, MA on June 7 of this year. Over the years, Seidel’s works have exhibited a long evolution from classical drones to the present mix of industrial and synthesized electroacoustic music. Seidel has an extensive background in experimental music, beginning as a guitarist in the 1980s downtown New York minimalist scene and later performing in various festivals throughout the US.. Since 1984 he has concentrated on the composition of drone and microtonal electronic music.

Read more“Not even Arvo Pärt’s Gregorian chants could save her.” When life tears your heart out, music has a way of suturing it back into place before you lose consciousness for good. This is what it feels like to immerse oneself in Trozos De Mí (Pieces Of Me), the latest project from Bogotá, Colombia-based pianist and composer Valentina Castillo (under the stage name Uva Lunera). Having previously explored her idiosyncratic blend of minimalism, groove, and songcraft across a travelogue of studio and live settings, she has produced what is, so far, her most intimate and transformational multimedia experience. Combining sound, text,

Read more2025 Festival of Contemporary Music at Tanglewood – July 24 – July 28, 2025 Every summer since 1964, the Tanglewood Music Center presents its Festival of Contemporary Music. According to Tanglewood’s materials: The Festival of Contemporary Music (FCM) is one of the world’s premier showcases for works from the current musical landscape and landmark pieces from the new music vanguard of the 20th century. FCM affords Tanglewood Music Center Fellows the opportunity to explore unfamiliar repertoire and experience the value of direct collaboration with living composers. Over the four FCM concerts (of the total of six) I heard carefully honed performances

Read moreThe Prom on July 31, presented by the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Joshua Weilerstein, as so many of the concerts during this stretch of time, included a work of Rachmaninov, the Symphonic Dances, which ended the concert. It began with Symphony No. 2 by Elsa Barraine, a composer unknown before this point to this listener. Barraine was a French composer, trained at the Paris Conservatory, where she was a student of Paul Dukas. The fact that she was a woman and Jewish and politically active made her life, both personal and professional, difficult during the time leading up to

Read moreThe performers for the Prom concert on July 28 were the BBC Scottish Orchestra and conductor Ryan Wigglesworth. The first piece, and, for a certain cohort, the most important was Earth Dances by Harrison Birtwistle. Written during 1985 and 1986, it is one of his major single movement pieces for large orchestra. The work features six strata, each with a characteristic intervallic “hierarcy,” register, and rhythmic characteristic. The interaction and progression of those strata, which defines its structure, produces a sense of a certain menacing quality and a sort of subterranean intensity, driving to a climax which Jonathan Cross in

Read moreTobias Picker NOVA Various Artists Bright Shiny Things Composer Tobias Picker won a Grammy for his 2020 operatic version of The Fantastic Mister Fox, and many pianists have first encountered him through the diatonic piece The Old and Lost Rivers. Picker has another side to his musical persona that is in no small measure reflective of his time as a student of Milton Babbitt, Elliott Carter, and Charles Wuorinen. The Bright Shiny Things recording NOVA includes chamber music that celebrates these high modernist roots, as well as forays into postmodernism. The title work is the latter, a riff

Read moreTo progressive musicians, Robert Wilson will always be most closely associated with Einstein on the Beach (1976), which in addition to being Philip Glass‘s most masterful and iconic work, is the one that most optimistically proclaimed the future of new music theater, liberated from narrative forms and the affected European accoutrements of opera singing and traditional orchestras. That disappointingly few works in its lineage have subsequently managed to approach its impact suggests that it may have been more of an outlier than a paradigm shift—a pinnacle of American minimalism at its most monumental, succeeded by a drift toward postminimalism and neoclassiciam with

Read more2025 Tanglewood Festival of Contemporary Music Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra July 28, 2025 LENOX – This year’s Festival of Contemporary Music was curated by composer Gabriela Ortiz. Born in Mexico City, Ortiz is one of the most prominent Latinx figures in twenty-first century classical music. Among other honors, she is composer-in-residence at Carnegie Hall and the Curtis Institute. Revolucióndiamantina, a recording of her music by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel, won three GRAMMY Awards in 2025. This year, FCM has spotlighted music from Mexico, as well as that of women composers. After four chamber ensemble

Read moreThe audience greeted John Williams like he was a rock star. Indeed, this composer’s music for blockbuster films like Star Wars, Jaws and Jurassic Park is well known and loved by billions around the world. People, including those in attendance at Tanglewood on Saturday night, July 26, love him for his concert music as well. Williams appeared on stage after the crowd-pleasing premiere performance of his Concerto for Piano and Orchestra with soloist Emanuel Ax and the Boston Symphony Orchestra led by Andris Nelsons. Williams has been a mainstay at the BSO for decades, having been music director of the

Read more