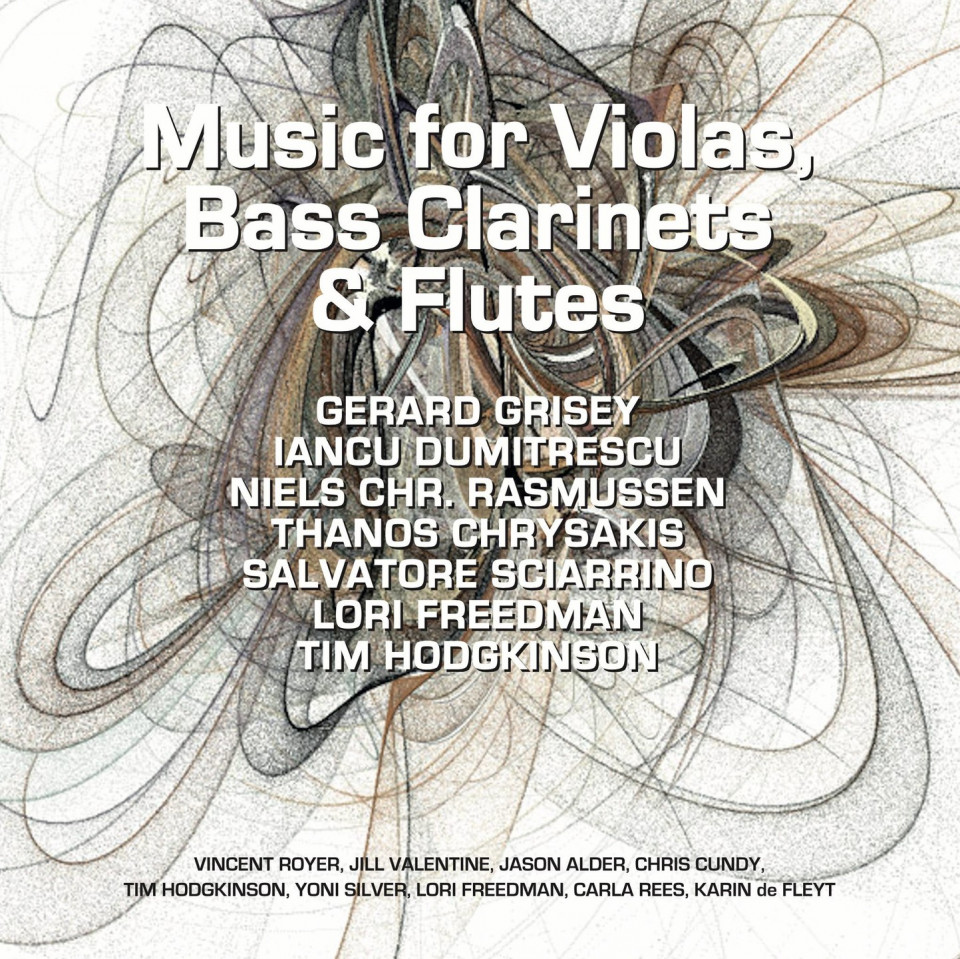

Released on Thanos Chrysakis’s Aural Terrains label, Music for Violas, Bass Clarinets & Flutes unfolds as a considered gathering of voices. The instrumentation itself suggests a downward gravity, an attraction to breath, wood, and string as sites of glorious friction. Across the program, Jason Alder, Tim Hodgkinson, Chris Cundy, Yoni Silver, and Lori Freedman inhabit the lower reeds with an intimacy that borders on corporeal. Vincent Royer and Jill Valentine draw violas into their extremes in either direction, while Carla Rees and Karin de Fleyt allow flutes to hover, flicker, and occasionally wound the air.

The album opens with Gérard Grisey’s Nout (1983) for solo contrabass clarinet, a work that seems to arrive already half submerged. Its quiet beauty is multiphonically arrayed, each tone carrying the weight of an interior life too dense to be articulated outright. There is a self-examining melancholy at work, like a nautilus shell cracked open to expose its chambers, once inhabited but now resonant only with memory. The sound moves forward hesitantly, aware of its own fragility, until it is pierced by something harsher and more elemental. A foghorn-like call slices through the darkness, a fleshly blade that refuses narrative consolation. In its wake, biography itself seems to dissolve. Footprints are erased by high tide, and what remains is the fact of sound as survival in a hostile expanse.

From this eroded shoreline, Niels Christian Rasmussen’s Gestalten (2018) for bass clarinet and tape introduces a different kind of tension, one between the human trace and an environment that feels uncannily clean. Bell-like sonorities bloom within the electronic layer, accompanied by exhalations and points of light that seem to puncture shadow rather than dispel it. Against this backdrop, the bass clarinet enters as an imperfect presence, its tone roughened by time, carrying residue wherever it goes. There is a sense that the instrument stains the surrounding purity simply by existing within it. The music dwells in this unease, allowing purity and profanity to entangle until neither can be isolated. What emerges is not conflict but recognition, an acknowledgment that human sound is always marked, always implicated, and therefore alive.

Thanos Chrysakis’s Octet (2018) expands the field outward, bringing together two violas, three bass clarinets, baritone saxophone, and two alto flutes in a work that feels ritualistic without ever becoming ceremonial. The relationships therein are tactile and deliberate, offered up as if to time itself rather than to any listening subject. Overtones converge and separate, brushing against the perceptual edge, creating the sensation of watching a film while remaining acutely aware of what lies beyond the frame. With the composer positioned behind the camera, we are left to infer motive and movement, to speculate about cause and consequence. Yet the music offers space rather than instruction. In the gaps between gestures, the listener is free to wander, gather fragments, and rearrange them into provisional meanings. The result is quietly linguistic, a vocabulary shaped by force and friction rather than syntax.

Salvatore Sciarrino’s Hermes (1984) for solo flute returns the focus inward, tracing a line between tenderness and restless wakefulness. The music moves with the unsteady logic of insomnia, never entirely abandoning itself to calm. Extended techniques shimmer at the edge of audibility, suggesting something otherworldly, an aura that hovers just out of reach. It is less an effect than a presence, something felt before it is understood. Karin de Fleyt’s performance captures this fragility with remarkable poise, allowing the flute to become both messenger and message, its divinity inseparable from the physical act of producing sound.

That sense of exposure deepens with Aura, a bass clarinet improvisation by Yoni Silver based on Iancu Dumitrescu’s work of the same name. Here, the terrain grows rougher, more unstable, as if structure itself were beginning to fail. Notes split apart under pressure, their internal components laid bare. The reed salivates, the sound fractures, and what might once have been wonder turns inward, confronting its own limits. There is a foreboding quality to this performance, an intuition of collapse, yet it is rendered with such honesty that it becomes strangely affirming. The beauty here is not decorative but visceral, emerging from a willingness to remain exposed.

Lori Freedman’s To the Bridge (2014) stands as the emotional and conceptual center of the album. Featuring the composer on bass clarinet, clarinet, and voice, the work introduces the human presence as a culmination. Her vocalizations recall the fearless inventiveness of Cathy Berberian, even while being wholly her own. The bass clarinet playing is extraordinary, coaxing from the instrument a saxophonic sheen that bristles with a charged, almost dangerous pleasure. Across these miniatures, Freedman traverses extremes of temperament, from boisterous assertion to quiet self-examination, never losing sight of the work’s fundamental drive. At its core, this is music about endurance, about finding ways to persist when language alone is insufficient.

Tim Hodgkinson’s Parautika (2019) follows with a kind of gentle recalibration. Scored for two violas and three bass clarinets, it might suggest density or weight, yet the prevailing impression is one of translucence. The gestures are brief, direct, and unencumbered by excess, allowing the music to communicate with immediacy. Even as the piece closes on a more declarative note, it feels earned rather than imposed.

The program concludes with Chrysakis’s Selva Oscura (2017/18) for viola and bass clarinet, a work that distills the entire preceding journey. Its language is pared down to essentials, each sound placed with intention, each silence given weight. It is a sustained meditation, etched onto the surface of an unfamiliar world. In its economy, it invites reflection rather than resolution. We are not transported somewhere else so much as returned, altered, to the selves we were at the outset.

Taken as a whole, this collection is marked by a rare integrity. Despite its reliance on extended techniques and abstract forms, it never relinquishes its commitment to storytelling, even when the contours of that story remain elusive. The music does not explain itself, nor does it demand comprehension. Instead, it lets listening serve as a form of dwelling. Thus, we are free to encounter ourselves without judgment, to leave changed in ways that may only become clear when time grants us the distance to recognize what has taken root.