On Monday, January 24, 2011 at 8:00 p.m. at The Bushwick Starr in Brooklyn, violist Wendy Richman of the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) will present “Viola & “, the first program in her “Vox/Viola” project, in which she presents new and important works for singing violist and/or electronics. The program features works by Arlene Sierra, Lou Bunk, Hillary Zipper, Kevin Ernste, Kaija Saariaho, Giacinto Scelsi and Sequenza21’s own Senior Editor, Christian Carey. I caught up with Ms. Richman via email to speak with her about the project’s origin and her interest in performing “one-woman duos.”

On Monday, January 24, 2011 at 8:00 p.m. at The Bushwick Starr in Brooklyn, violist Wendy Richman of the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) will present “Viola & “, the first program in her “Vox/Viola” project, in which she presents new and important works for singing violist and/or electronics. The program features works by Arlene Sierra, Lou Bunk, Hillary Zipper, Kevin Ernste, Kaija Saariaho, Giacinto Scelsi and Sequenza21’s own Senior Editor, Christian Carey. I caught up with Ms. Richman via email to speak with her about the project’s origin and her interest in performing “one-woman duos.”

“It’s not entirely fair for me to say all the pieces are one-woman duos,” she says. “There’s a very active partner, sound designer Levy Lorenzo, doing much of the program with me.” The idea for these programs goes back several years, growing in part out of Wendy’s involvement with a number of composer friends who happened to work extensively with electronics, but “also because I liked the idea of having a recital program that was totally self-contained. In my imagination, I could pack my laptop, mic, and a pedal, meet with a sound guy for 10 minutes, and—bam!—the show would go perfectly.”

The reality of doing recitals with live electronics proved more complicated than Richman imagined, however, until she met Lorenzo while performing Kaija Saariaho’s Vent Nocturne at an ICE Saariaho portrait concert in New York’s The Tank, where Lorenzo was the audio engineer. “I really experienced the piece differently during that performance. Levy is a fantastically sensitive musician, in addition to [having] great technological skills. Maybe it was in part the rather cramped quarters of the Tank, so we were essentially onstage together, but I’d never really approached playing this music as a duet. Now, it’s really important to me to approach it that way, so the electronics part is not only ‘live’ but ‘alive’.”

“About five years ago,” she adds,” I began playing Scelsi’s Manto, a three-movement work whose movements can be played separately, all together, or in any pairing. The last movement’s instruction states that it is for ‘altiste/chanteuse (necessarily female),’ and ‘the text is a speech of the Sibyl [a prophetess or seer].’ I was learning the piece during a really hard time in my life, when I was recovering from a bad accident, and I think I was looking for music that really spoke to me. Well, the Scelsi did! I guess I was speaking/chanting to myself, (because) it was the first piece in a long time that I had an extremely visceral response to, and that particular commitment seemed to speak to audiences. I received really positive feedback about it and began to feel that it was my piece.”

While there are a number of violinists who sing and play at once (Courtney Orlando of Alarm Will Sound and Monica Germino, of the Dutch group Elektra come to mind), singing violists remain something of a rarity. “I knew that there were some other string players who had done similar things but hadn’t heard much about viola/voice works aside from the Scelsi, and basically I just thought it would be a fun project for me to do.”

So at the urging of the composer Ken Ueno, Ms. Richman embarked on blazing a trail as a singing violist commissioning a number of composers to write pieces for her. The commissioning process, she says, was refreshingly informal and casual. “I talked to composer friends and told them that I don’t have any money (yet!) but that I’m fairly confident I can get a decent number of performances. Their responses varied, of course, but for the most part they were all interested and it was just a matter of time (many had paying commissions that would obviously take priority). I currently have eight finished pieces (three of which are being premiered on the 24th), and a total of about twenty composers who have committed to writing things over the next few years.”

The group of composers on the “Viola & “ program represents a highly eclectic and diverse group. This may seem unusual, but it stems from Ms. Richman’s refreshingly open and friendly approach to commissioning new works. “After hearing (a composer’s) music and liking it, the most important thing for me is that I like the composer (himself) and want to work with (him). In some ways, that’s more important to me, because they might find themselves making stylistic adjustments anyway given the relative newness of the genre to them. I needed to feel like we connected as friends so I could be really comfortable in the collaborative aspect of the project.”

Viola &

Violist/vocalist Wendy Richman and Engineer Levy Lorenzo

Part of The Forge’s Forgefestival

Monday, January 24, 2011 at 8:00 p.m.

Admission: $10

The Bushwick Starr

207 Starr Street

Brooklyn, NY 11237

Info Line: 201.875.8573

www.theforgenow.com

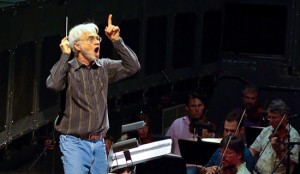

Conductor Steven Dennis Bodner, who was a passionate, fiery, radical force for new music, died tragically on Monday night after a brief illness. Steve was a fanatically devoted new music performer and advocate, who helped develop a new appreciative audience for this music during his tenure as conductor of the Williams College Wind Ensemble and the Opus Zero Band, the college contemporary music group which he founded. He was a man of incredible depth, joy and energy whose early death is not only a great personal loss to those who knew him but is an immesurable loss to the contemporary music field, where Steve would have had a wider influence if fate had not intervened.

Conductor Steven Dennis Bodner, who was a passionate, fiery, radical force for new music, died tragically on Monday night after a brief illness. Steve was a fanatically devoted new music performer and advocate, who helped develop a new appreciative audience for this music during his tenure as conductor of the Williams College Wind Ensemble and the Opus Zero Band, the college contemporary music group which he founded. He was a man of incredible depth, joy and energy whose early death is not only a great personal loss to those who knew him but is an immesurable loss to the contemporary music field, where Steve would have had a wider influence if fate had not intervened.

The Takacs Quartet gave the U.K. premiere of Daniel Kellogg’s Soft Sleep Shall Contain You, a hauntingly beautiful, touching “Meditation on Schubert’s Death and the Maiden.” The BBC has made the performance available online here.

The Takacs Quartet gave the U.K. premiere of Daniel Kellogg’s Soft Sleep Shall Contain You, a hauntingly beautiful, touching “Meditation on Schubert’s Death and the Maiden.” The BBC has made the performance available online here.

Kellogg’s quartet is a simply beautiful, evocative work that comments–at times gently, at others savagely, ultimately transcendently–on the refrain of Schubert’s famous song, “Death and the Maiden” (and, by extension–and design–the string quartet which bears its name thanks to the variation movement based on this same music). It is a little gem, its biggest–and only–flaw, perhaps, that it feels slight for a piece that is nearly 15 minutes long (although perhaps that’s not much of a flaw at all). This is music that manages to comment on the past while making a statement of its own time, that challenges without alienating and uplifts and enlightens without being patrionizing. A deeply moving work performed impeccably by one of the world’s premiere string quartets.

Hats off, ladies and gentlemen!

For the past week I’ve been in residence at the 2010 2010 Interamerican Festival for the Arts This is doubly significant for me: for one thing, and most obviously, it’s an excellent professional opportunity providing a very fine orchestral performance (and a second performance of an orchestral work at that!). For another, I was born and raised in Puerto Rico. Although I have been active in the U.S. and have lived most of my life there since the age of 16, Puerto Rico is still my home in a very real way and being performed by my hometown band is a source of great pride.

For the past week I’ve been in residence at the 2010 2010 Interamerican Festival for the Arts This is doubly significant for me: for one thing, and most obviously, it’s an excellent professional opportunity providing a very fine orchestral performance (and a second performance of an orchestral work at that!). For another, I was born and raised in Puerto Rico. Although I have been active in the U.S. and have lived most of my life there since the age of 16, Puerto Rico is still my home in a very real way and being performed by my hometown band is a source of great pride.

I don’t want to toot my own horn here, however. PRSO Music Director Maximiano Valdes , beginning his second full season in this post, is determined to turn this festival into a major contemporary music festival for the Caribbean and Latin America, and, thus, the programming this past week has consisted primarily of new music with tonight’s performance by the PRSO consisting entirely of music by living composers, all of whom will be in attendance. Besides my own 2007 work, “Colorfields,” we are hearing premieres of works by Pittsburgh New Music Ensemble founder David Stock and University of Puerto Rico professor and festival co-director Carlos Vazquez, who presents a guitar concerto that pays tribute to the folk music of Panama, for whose principal symphony orchestra the work was written. The most impressive composer by far on this program, however, is the Argentinian/Spanish composer Fabian Panisello . Panisello, who was trained in Argentina and throughout Europe, is the director of the Plural Ensemble in Madrid and has racked up an impressive list of accomplishments in Europe but remains largely unknown in the U.S. (although upcoming residencies at UC Davis and Stanford should hopefully begin to change this). His music, at times spectral, at times straightforwardly tonal, is always impressive, always evocative and often horrifying in its power and transcendent in its beauty. More than having the chance to build a relationship with my hometown band and to hear a large piece of mine again, it has been encountering Panisello’s music that has made the biggest impact on me this week.

So, two things to watch out for: Fabian Panisello and his music and the Interamerican Festival for the Arts, which, if Maestro Valdez is succesful in his endeavors (and his panache, ambition and musicianship suggest to me that he will be) will become the major venue for contemporary music in the Caribbean and Latin America, and a bridge between composers and interpreters throughout the Americas.

The National Symphony Orchestra has been hosting composer John Adams over the past two weeks in presentations of his own works as well as works of the 20th century American, Russian and English repertoires. Last week he presented works by Copland, Barber, and Elgar as well as his own The Wound Dresser. This week, Adams and the NSO were joined by violinist Leila Josefowicz for a performance that included Adams’ electric violin “concerto,” The Dharma at Big Sur, and the Washington premiere of the Dr. Atomic Symphony.

The program began with Benjamin Britten’s “Four Sea Interludes” from his opera, Peter Grimes. While the opening “Dawn” interlude began on somewhat shaky ground, Adams quickly proved himself a capable conductor of this repertoire. The composer has been doing a lot of conducting over the past decade and it’s beginning to show. His confidence as a conductor, particularly one of pre-WWII 20th century music, has grown by leaps and bounds and the NSO’s playing under him reflected this. Whenever Adams conducts, however, he always presents his own work (it is part of the attraction, after all) and where in Britten and Stravinsky he is confident and capable, in his own work Mr. Adams is simply superb.

The Dharma at Big Sur, not so much a formal concerto for six string electric violin so much as a rhapsodic evocation of cross-country travel , California mythology, and the poetry and prose of Jack Kerouac. This is a powerful work, conveying a joyful energy that is simply infectious. The violin carries the bulk of the musical argument in the piece, with very few tutti moments offering rest from some highly energetic, virtuosic music, and Ms. Josefowicz astounds in her role as Kerouac’s musical manifestation. Her playing is a revelation and she simply OWNS this part. One hopes that she and Adams will come to record the piece sometime, not so much to replace the original 2006 recording with Tracy Silverman, the violinist for whom the work was written, but to complement it, as Ms. Josefowicz brings an exuberant energy to the piece that is just on the edge of wildness, where Mr. Silverman’s recording seems much more sedate by comparison.

After intermission, Mr. Adams and the orchestra took on Stravinsky’s early, slight orchestral showpiece, Feu d’artifice (Fireworks). They handled the work expertly, certainly, but it is a work that has failed to make much of an impression upon me through the years as little more than a youthful work by a composer on the verge of greatness. Indeed, the second half was really all about the Dr. Atomic Symphony, a reworking of material from Adams’ 2005 opera, Dr. Atomic. While the symphony obviously owes a great deal to the opera (and Adams, both in his speeches to the audience in between numbers and in the program notes, rather redundantly stressed the musical connections with the opera’s plot) it is certainly worthwhile as a free-standing work and does not really need any programmatic allusions to make its point. This is a harrowing symphony, full of a wild energy that proves the dark contrast to The Dharma at Big Sur’s sublime apotheosis, and the NSO and Adams gave it a duly appropriate reading which deservedly brought the house down. And while the symphony makes a visceral impression, it is also governed by a Sibelian formal logic that makes it an important addition to the somewhat dormant American symphonic tradition. It will hopefully prove to be one of Adams’ truly major works.

The National Symphony Orchestra, Leila Josefowicz, violin, under the direction of John Adams, will repeat this program on Friday, May 21 at 1:30 p.m. and Saturday, May 22 at 8:00 p.m. at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.

On Friday, April 30, 2010, my ensemble, Great Noise Ensemble, will present the last concert of our 2009-10 concert season. The program, presented at Ward Hall, on the campus of the Catholic University of America at 7:30 p.m. (Visit www.greatnoiseensemble.com for tickets if you’re in the Washington region this Friday), is a unique program featuring a new work for mixed ensemble and sculpted percussion by composer D.J. Sparr in collaboration with artist Terry Berlier of Stanford University. The 41st Rudiment, named after the 40 “rudiments” that percussionists study as they develop their craft, represents one more rudiment indicative of the experimental nature of Berlier’s instruments. It was written for percussionist Christopher Froh, of the San Francisco Contemporary Chamber Players, and Great Noise Ensemble.

D.J. Sparr initially pitched the piece that would become The 41st Rudiment to Great Noise Ensemble’s board some five years ago. “The idea came through wanting to work with Chris Froh,” he says, “whom I had seen out on an amazing concert in Ann Arbor years back. I was in the Bay Area, so we went out for drinks, and over the course of the conversation we talked about finding instruments at a hardware store… and somehow, collectively we came up with the idea that we should ‘build something.’ From there, we started talking about what that would be, who might be interested collaborating with us, etc.” After searching for an appropriate collaborator it was Froh who suggested that they work with Terry Belier. “Terry and I worked on another project together a few years ago with the Empyrean Ensemble and Italian composer, Luciano Chessa. I played one of her sculptures then (an earlier “panlid gamelan”) and fell in love with her aesthetic. When D.J. and I first started talking about this project some five years ago, I suggested asking Terry to be involved.”

“A few years ago,” writes Terry Berlier, “ I was working on a piece called ‘Two pan tops can meet’ (2003) which was based on the homophobic Jamaican saying ‘Two pan tops can’t meet.’ (I had worked in Jamaica for two years as a Peace Corps Volunteer from 1995-97.) That first piece used thrift store pan lids as speaker housings that played a sound piece. But while I was sifting through the pan lids, I started setting aside the pan lids that resonated strongly. These eventually became Pan Lid Gamelan I in 2003 and gallery viewers were invited to play it.

In 2008, Composer Luciano Chessa wanted to compose this sculpture/instrument into one of our collaborations (Inkless Imagination IV) and I was excited to have a professional percussionist, Chris Froh, play them. A few years later, Chris asked if I would like to work with him again on making sculptures specifically for him to play and work with D.J. Sparr.”

D.J. Sparr has been building a reputation for many years now as a composer of rhythmically charged and energetic music (the Alburquerque Tribune once referred to his piece for eighth blackbird, The Glam Seduction as “Paganini on coke”) that merges classical conventions with rock idioms. The 41st Rudiment is no different, although the rock influence this time is far subtler than in the works that gained Sparr his early reputation. “I am always influenced by the drama of a rock-and-roll concert, and in this work, the drummer is the superstar… he engages the other players in ways to entice them to join in with him in gestures and call-and-response melodies…much the same as would happen in a rock-band scenario where guitarists, drummers, and bass players trade solos. This work,” however, “is heavily influenced by the baroque concerto grosso form as the large scale form is comprised of many short movements. There are elements of Bach and Vivaldi, but there are also elements of other things: Satie Gymnopédies; Spanish barcaroles; improvisatory structures such as Zorn’s Cobra; and many cadenzas and improvisation.”

Thursday, April 15 marked the New York premiere of Louis Andriessen’s latest opera, La Commedia at Carnegie Hall. I was lucky enough to make it up to New York for this event.

— Full disclosure: part of my trip to New York was to meet with Andriessen to discuss my plans for performing his 1984-88 opera, De Materie in Washington, D.C. this coming October. I’ll be blogging a lot about that process in the coming weeks, so stay tuned. Frankly, I am as addicted to Andriessen’s music as the composer is to garlic (which I found out over bread and some very strong garlic dipping sauce over lunch) so I was glad to live within easily-traveled distance of New York and be able to attend this performance. Anyway, this is all by way of a caveat that what follows may not be the most impartial review; I hope you’ll forgive me.

Andriessen’s work can be divided, somewhat, into periods based on one or two large works which define his compositional interests over the span of a decade or so. De Staat, the work that brought him to international prominence in the 1970’s, provides a framework for the politically radical works that drove him in the decade of ca. 1968-1978/79. De Materie frames his work of the 1980’s within the context of metaphysics and the spiritual world that culminates in 1996-97’s Trilogy of the Last Day, which overlaps with (and is unfortunately—at least in the U.S.—overshadowed by) Andriessen’s operatic collaboration with Peter Greenaway in Rosa (1994) and Writing to Vermeer (1997-98). La Commedia, likewise, reflects Andriessen’s principal interests in the first decade of the 21st century and, in a way, bridges the Trilogy’s preoccupation with death with the theatricality of the Greenaway operas.

La Commedia is a “film opera” based, loosely, on Dante’s Divina Commedia. Its production is by the American film director Hal Hartley, with whom Andriessen collaborated on other theatrically hybrid projects like The New Maths (2000), Passeggiata in tram in america e ritorno (1998), and the opera Inana (2003). Due to budgetary constraints it was presented without the film in a “semi-staged” concert version on Thursday night. While this is unfortunate in depriving the New York (and, earlier in the week, Los Angeles) audience(s) of an important aspect of the work, the abstractness of Andriessen’s treatment of his subject may very well be enhanced by the concert presentation, for this is not traditional opera by any stretch of the imagination and stretches the definition of the genre beyond the composer’s earlier work with Peter Greenaway (in fact, it has more in common with the earlier De Materie in terms of formal presentation than it does with Writing to Vermeer or the surreal romp, Rosa).

In La Commedia, only two of the four lead vocal parts retain a specific role. Claron McFadden, in the role of Béatrice, was a revelation. Her voice truly heavenly in the role with each of her disappointingly few moments on stage highlight some of the most beautiful music Andriessen has ever written. Perhaps the most beautifully magical moment in all of La Commedia, however, belongs to Marcel Beekman in the tiny, surprising role of Casella. Casella, a friend of Dante’s youth who died, unexpectedly at a relatively young age and who was himself a musician and composer who’d set, according to Purgatorio, canto 2, a love poem from Dante’s earlier work, “Convivio”. As Dante arrives in Purgatory he hears his friend singing this familiar song and Andriessen’s setting of this moment manages to capture the ethereal beauty of that moment early on in Dante’s poem. Beekman’s voice, emerging Thursday night from within the audience (surprising those sitting next to him), possesses a sweetness rare among tenors and his aria, joined briefly at the end by Jeroen Willems’ (at the moment) Dante, was, for me, a highlight of the evening.