On Saturday, April 6, 2024 the Santa Monica Public Library and the Cold Blue Music recording label presented a concert titled An Afternoon of Double Basses and Piano. This was the latest incarnation of the Soundwaves series of new music concerts, now back in business after the Covid pandemic. The library auditorium was undergoing some renovation, so this concert was held in the nearby Edye Theater at the Broad Stage, part of the Santa Monica College Performing Arts Center. There were three works presented: Darkness and Scattered Light, by John Luther Adams, featuring five double basses, Flying, by Christopher Roberts, for three double basses and Tiny Thunder by Nicholas Chase, a world premiere for four-handed piano.

The first piece on the program was Darkness and Scattered Light, by John Luther Adams. This work appeared on a Cold Blue CD in 2023 and is scored for five double basses. In the Cold Blue recording the late Robert Black, a highly regarded bass player and member of Bang On a Can, performed all five parts separately. These were then precisely mixed for the final realization, no doubt taxing the masterful skills of even a Robert Black, who subsequently received a Grammy nomination for his efforts. For this concert, the work was performed live with five individual double basses: James Bergman, Christopher Roberts, John Graves, Hakeem Holloway and Jeff Schwartz. All were conducted by Nicholas Deyoe..

Darkness and Scattered Light was inspired by the natural changes in the character and quality of light during 24 hours of a winter solstice. The piece begins with a deep, sustained foundational tone. More long notes enter with the layers of sound building as the dynamic rises and subsides. The overall effect is like the swelling and surging of ocean waves. The languid feeling persists as the piece continues with individual phrases multiplying in a series of entrances and exits of the five basses. This piece is all about sonority, power and the shaping of the texture. At times it seems as if the sound itself is in slow motion. Occasional phrases comprised of very high pitches are heard rising above the lower tones, and this makes for challenging playing. The coordination of the five double basses by Nicholas Deyoe was outstanding given the varied layers and many changing contours of the music. As the piece neared its conclusion the sounds became deeper and richer as each of the basses dropped out in their turn. Darkness and Scattered Light is an ambitious work given that its viewpoint is so firmly fixed in the lowest registers. The sculpting of such deeply rich bass sounds make for an unusual and compelling listening experience.

Flying, by Christopher Roberts, followed, and this is the fourth movement from a larger work, Trios for Deep Voices, drawn from experiences in the jungles of the Star Mountains region of Papua New Guinea. Flying is scored for three double basses and was performed on this occasion by James Bergman, Jeff Schwartz and the composer. The piece opens with a high pitched melody from a single double bass that establishes a lovely feel that is consistently upheld throughout. The other two basses join in with busy lines, filling the air with a roar of notes from the lower registers. There is an almost nostalgic feeling as the repeating cells develop into a satisfying groove. The deep harmonies that emerge are especially effective.

As the piece continues, one bass provides a solo line with somewhat higher pitches while the two others add to the actively repeating patterns below. Good coordination between the players keeps all of this on track and the result is a pleasing warmth with an optimistic sensibility. Flying radiates affection with a pleasant sincerity that only the double bass can conjure.

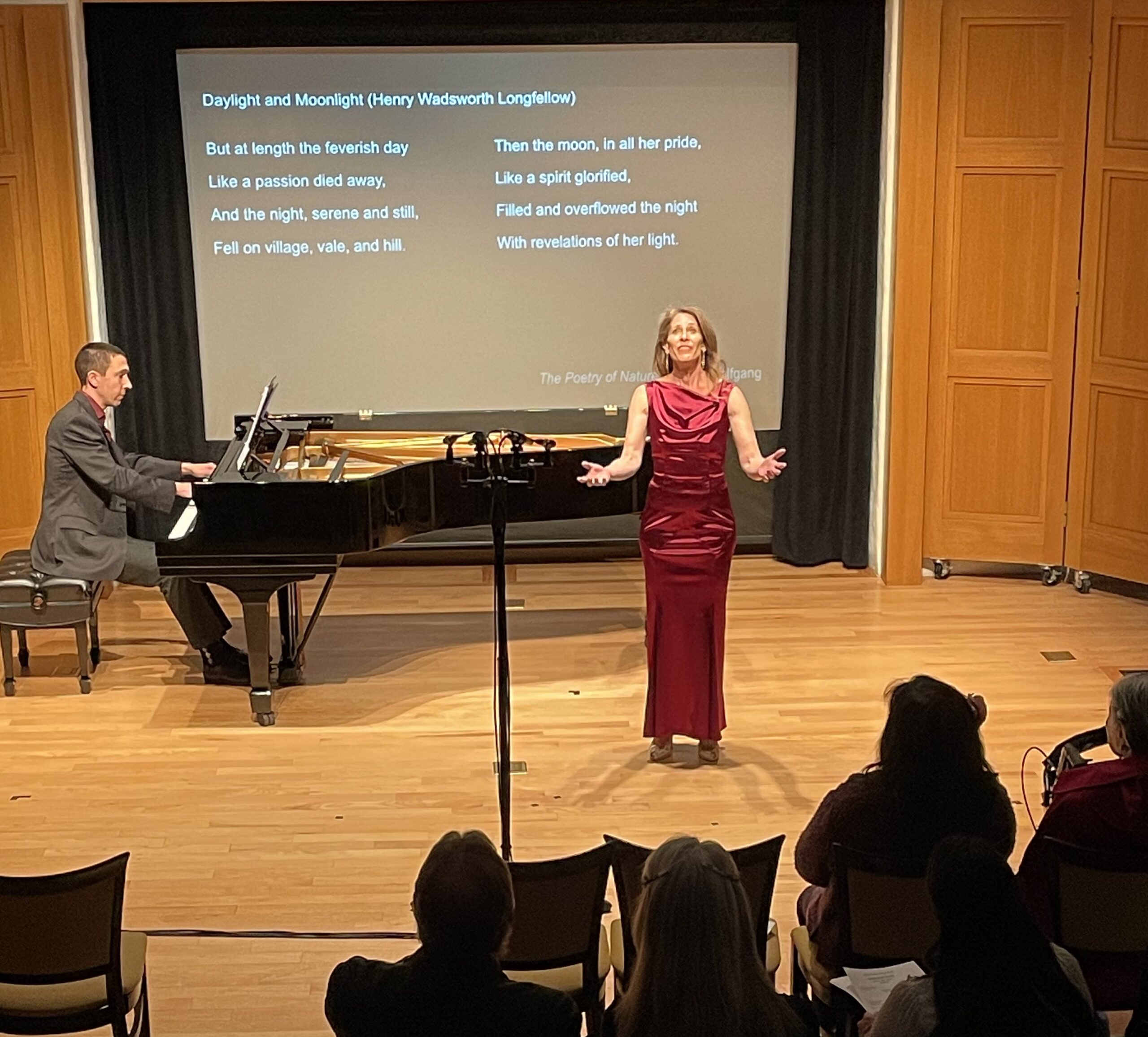

The final work on the program was Tiny Thunder by Nicholas Chase, a world premiere. This is an extended piece for piano, four-hands, performed by Bryan Pezzone and Jennifer Logan. Often a four-hands piece will feature a lot of technical flash, as if the composer is determined to keep 20 fingers in constant motion. Tiny Thunder is a refreshing departure in that it is a softer and more intimate experience. The opening is a series of quiet, single notes that seem to hang in the air. A call and response develops between the two players, but this is never hurried or insistent. As the piece proceeds, lovely spare harmonies develop from minimal musical materials held to a modest tempo. There is a quiet, settled feel to this with solemn chords rising up from the lower registers.

At times, the four hands become more active with a light melody that compliments the continuing lower chords. At other times, only single notes are heard in each part, simple and solitary. Towards the finish, trills and ornamentation swell into a more active texture, adding another level of elegant expression. At the finish, the tempo increases and strong chords rise up from below with some discord in the harmony. The dynamic builds up to loud for the first time with active, repeating lines from both players. A sudden stop to the music ends the piece. A long, reverent silence was observed by the audience before the enthusiastic applause. Tiny Thunder is an idealized piece for two friends who enjoy playing together without need of musical fireworks or fortissimo dramatics.

The return of the Soundwaves concert series after the covid pandemic is a welcome contribution to Santa Monica cultural life. The next concert will feature the Joe Baiza Quartet at the Santa Monica Public Library on May 4.