The birthdays of Harrison Birtwistle and Peter Maxwell Davies, both of whom turn 80 in 2014, is one of the major focuses of this year’s Proms. Each has a complete Proms Portrait matinee concerts in Cadogan Hall dedicated to their music on August 30 (Davies) and September 6 (Birtwistle), and Davies’s birthday, on September 8, is marked with a late night Prom in the Albert Hall. Unfortunately I will not be around for any of those concerts, but I have heard other concerts marking the birthdays.

On August 9, in Cadogan Hall on a Saturday matinee concert combined the birthday strand with another theme of this summer’s Proms, presenting orchestras new to the festival and from far afield. The Lapland Chamber Orchestra, conducted by John Storgårds, presented a concert which included Birtwistle’s Endless Parade, with Håkan Hardenberger as the trumpet solo, and Davies’s Sinfonia. The Birtwistle, for trumpet with vibraphone and strings, written in 1987 for Hardenberger, was intended by Birtwistle, who had, he said in the short discussion before the performance, cubism on his mind, as a study in discontinuity, cross cutting six kinds of music, with different tempi, figuration, and textures, in disconnected and apparently illogical ways. Birtwistle also apparently had Stan Kenton on his mind, and there is from time to time a sort of whiff of jazziness in the music, although that may be as much an effect of the sound of the vibraphone as the actual notes.

The Davies Sinfonia was written in 1962, after he had studied in Italy with Petrassi, but before he had gone to Princeton to study with Sessions and before he had begun work on Taverner, the central work of his early career. It was written under the influence of the Monteverdi Vespers and makes use of procedures from that work. The work is in Davies’s earlier, post-Webernesque Euoprean modernist style, but nonetheless has in it the beginnings of the isorythmic cantus firmus procedures that one recognizes in slightly later and possibly more characteristic piece such as Antechrist.

Both of these works received very strong, very strongly characterized, and highly persuasive performances. The concert began with a Symphony by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, and also offered, between the Birtwistle and Davies, Honegger’s Pastorale d’été, and ended with Rakastava by Sibelius, a very beautiful piece for strings and percussion, of whose existence prior to this concert I had been completely unaware.

Storgårds conducted the BBC Philharmonic on August 14 in Proms concert at Albert Hall that featured Davies’s Fifth Symphony, along with works of Sibelius (Finlandia and the Second Symphony) and Frank Bridge (Oration for ‘cello and orchestra, with Leonard Elschenbroich as the soloist). Written in 1994, when Davies performing career had moved from working with The Fires of London to conducting orchestras, mainly the BBC Philharmonic and the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, the Symphony is in one movement and reflects Davies’s involvement at the time with the Sibelius Sixth and Seventh Symphonies, which had figured in his repertory. The Symphony which at first seems to be in discontinuous shards, consists of the braiding of a fast music with increasing intensity and emphaticness and an equally impassioned and forward moving slow music with a motionless music providing moments of stasis in the overall progress, which in certain respects resembles the arc of the Sibelius Seventh Symphony. It is a highly dramatic piece and it received a very dramatic and impassioned, although somewhat under-shaped performance. This Prom was preceded by a Composer Portrait concert at the Royal College of Music in which Davies talked to Andrew McGregor about his chamber works Antechrist, Runes from a Holy Island, and Six Sorano Variants, which were given excellent performances by Musicians of the London Sinfonietta Academy.

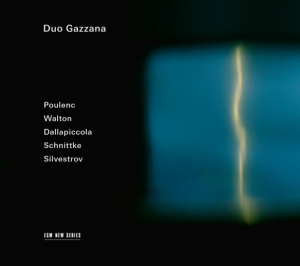

Two nights earlier The BBC National Orchestra of Wales, conducted by Thomas Søndergård, presented the suite from the second act of Davies’s ballet Caroline Mathilde, along with the Violin Concerto of William Walton and more music of Sibelius, The Swan of Tuonela and the Fifth Symphony. Walton’s rather elegant and glamorous concerto is just the sort of piece that one would have written for Heifetz, who, in fact, commissioned it and gave its first performance, and it received a suitably luxurious performance from James Ehnes. Davies’s ballet is about the misadventures and eventual downfall of the title character, the sister of George III of England who, at the age of 15, was married to the Danish king Christian VII and who became the lover of his person physician, with attendant unfortunate personal and political consequences. The music from the ballet is, compared to more austere and abstract works such as the Fifth Symphony, relatively easy listening and depicts fairly clearly the story line of the choreography. The performance mirrored the clarity and sonorous beauty of the orchestral writing.

Davies’s birthday is also being celebrated by other festivals. The North York Moors Chamber Music Festival in North Yorkshire between August 24 and August 30 features a work by him on each of their concerts. I heard the concert on August 25 in the beautiful Victorian Gothic Church of St. Helen’s and All Saint’s, in Wykeham, in which the Quartetto di Cremona began the concert with the Beethoven Quartet, Op. 74 and ended it with Davies’s 6th Naxos Quartet. In the between another quartet, consisting of Zsolt-Tihamér Visontay, Simone Brown, Meghan Cassidy, and Jaimie Walton played the Berg Lyric Suite. The 6th Naxos Quartet is a big, thirty minute long, impassioned piece which interpolates into a fairly traditional four movement layout, two short “arrangements” of plainsong hymns for the third Sunday of Advent and for Christmas Day, the day the piece was finished. All of the performances on this concert were outstanding.

The Proms was also marking the 80th birthday of the British born American composer Bernard Rands with the first UK performance of his Piano Concerto performed by Jonathan Biss and the BBC Scottish Orchestra, conducted by Markus Stenz. The Concerto is an imposing work which presents the soloist as a predominant member of the ensemble rather than, as Paul Conway’s program note said, “a protagonist striving heroically for supremacy over massed accompanying forces.” After a bright and lively first movement, entitled Fantasia, the second and third movements, were not clearly enough differentiated, especially in terms of tempo, as opposed to speed of figuration, to remain as separate impressions on this listeners memory.

On August 17, the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra and Andrew Manze presented a concert entitled “Lest We Forget,” to commemorate the centennial of the First World War. The first half consisted of works written by composers who died in the war. The German composer Rudi Stephan (1887-1915), who died in the trenches of Galicia on the eastern front, was represented by Music For Orchestra from 1912, which was steeped in the language of late German romantics particularly Strauss. The Elegy for Strings in memoriam Rupert Brooke (who had himself died in the Navy in the war) by Frederick Kelly (1881-1916), who died in the last phase of the battle of the Somme, reflects more of the language of Debussy. Both of these works were indications of great potential as yet unrealized, especially the Stephan. A much stronger and more personal impression was made by the Six Songs from ‘A Shropshire Lad’ by George Butterworth (1885-1916), who also died on the Somme. He was a more fully developed composer, and several of his works, including these songs, which he wrote with piano accompaniment, but were performed here in a orchestration by Phillip Brookes, are fairly well known and not infrequently performed. Two of them, Loveliest of Trees, and The Lads In Their Hundreds, are, I think, particularly good. They were sung, more of less perfectly, by the baritone Roderick Williams, with a beautiful sound and perfect British English diction; it is hard to imagine anyone ever doing them better. The concert ended with the Vaughan Williams Third Symphony, written after the war, but formed by his experiences as an ambulance driver in France during the conflict. I was very excited to hear this piece, which I’ve know since I was in high school, but had never heard live. The performance was all that one could wish for. There were a number of other Vaughan Williams pieces on the Prom presented by the BBC Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sakari Oramo, on August 13: The Overture to the Wasps, The Lark Ascending, and his big ballet (or as he called it ‘a masque for dancing’) Job. These performances were rather less radiant than that of the Symphony, but they did bring to mind what a very good composer Vaughan Williams was, and, especially in pieces like Job, people often don’t remember, a modernist.

All of the Proms concerts can be heard at http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b007v097/episodes/player