Since no one listens to contemporary classical music, and it doesn’t get put on concert programs, to have a new work not only recorded but recorded again, by different musicians, is an impossible dream. But that’s what happens when you’re John Adams, America’s leading composer. And deservedly so, because he’s a deeply skilled and intelligent composer with serious things to say and the aesthetic to say them clearly, expressively and winningly without pandering to or patronizing his audience.

But he is a busy man, and some of his recent work, like Absolute Jest and The Gospel According to the Other Mary seems more assembled from parts of pieces he (or, in the case of the former, Beethoven) has already made than thought through and composed. That’s been particulary frustrating, since his String Quartet, which I saw premiered in 2009, is not only a terrific piece but one that seemed to have opened the door to a new, late style.

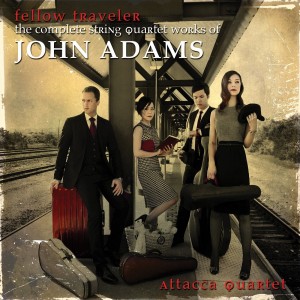

The St. Lawrence Quartet was the original dedicatee, the ensemble that played it in public and recorded it first. Their intense, nervous energy was exactly right for the sinewy, restless music. Now they’ve been followed by the Attacca Quartet, with a Fellow Traveller, a new CD of Adam’s complete works for String Quartet. Their manner with the piece is very different, and that’s a strength of the recording that also serves the quality of the composition.

What is most interesting about the String Quartet is how Adams, who is fundamentally a Neo-Romantic composer with a great facility for tension, release and powerful expression, uses repetition to create a sensation of agitation, but this time without much resolution. At the Attacca’s enjoyable CD release performance at (le) poisson rouge, Adams spoke about harmony and how he believes that a facility for it is necessary for composers. But the Quartet is one of his least harmonically rich pieces, it subtly reaches back to Minimalist experiments like “Christian Zeal and Activity.” It’s also more closely related to Beethoven, who was of course a magnificent harmonist but whose secret power was always rhythm, especially building and releasing tension by moving the downbeat around to different parts of measures while maintaining the same meter.

That’s what Adams does in the Quartet, plays around with the rhythmic possibilities of short phrases, different lengths, different pulses. There’s a lot of chattering interplay that add to the overall dynamism and the whole builds to an evocative and enigmatic payoff. The Attacca plays this with less muscular vigor than the Borromeo but with more thoughtfulness, more introversion, and so bring out the internal mysteries of the music, and the swing a little bit more. They also are a more lyrical ensemble, and they pay more attention to phrasing than attack and articulation, and the results are not only expressive but place the music directly in the long history of Western classical music. I can hear the Haydn and Beethoven that is part of their memories.

That approach also pays off in John’s Book of Alleged Dances, which is both amusing in intent and seriously well-made. This is extroverted music, and the Attacca plays it that way, which adds to the impression that larger piece gives. Dances is not first-rate Adams, but especially in person, the Attacca give it a first-rate performance.

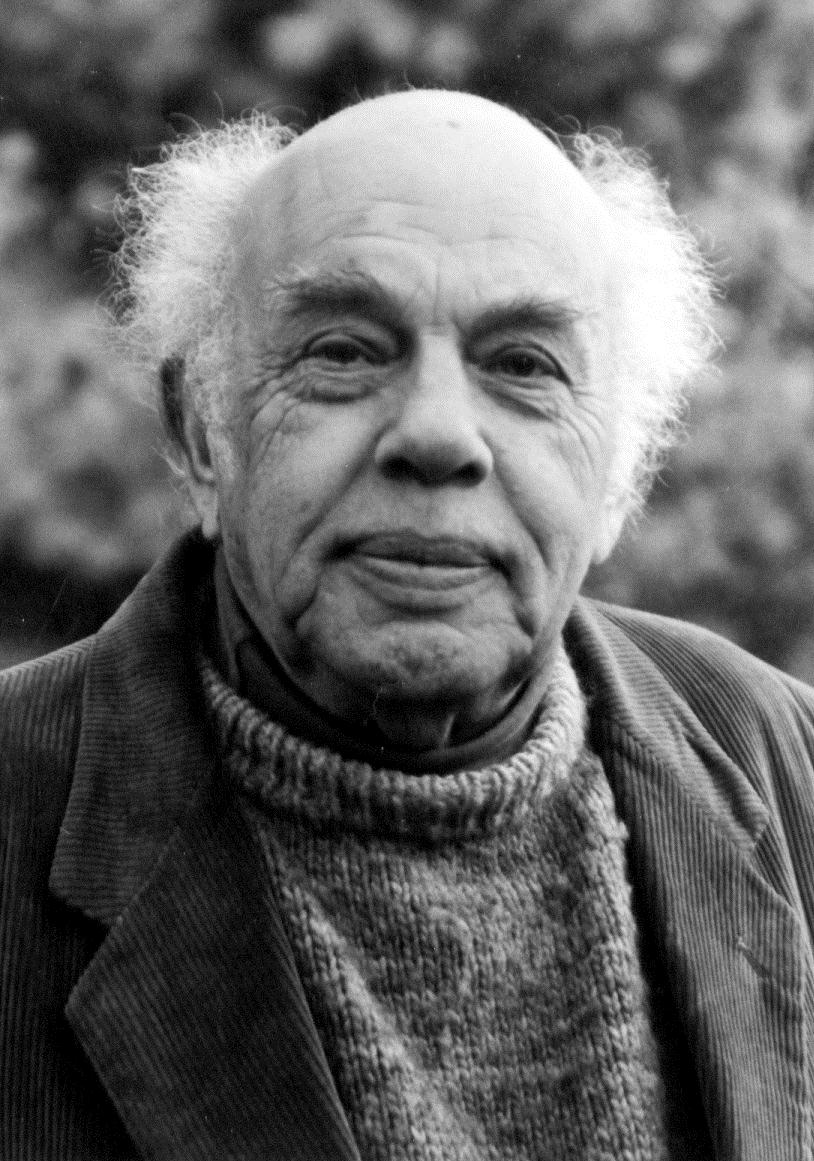

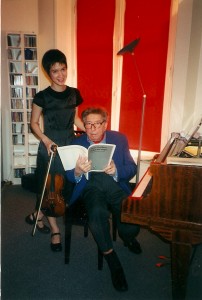

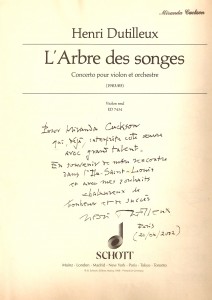

My visit to Henri Dutilleux was part of one of the most beautiful summers I’ve had. I stayed for several weeks in Paris just before beginning my doctoral degree. I was determined to pass out of the language-course requirement, so I rented a little apartment on the Rue du Cardinal-Lemoine and immersed myself in French, reading twenty pages a day, chatting with storepeople and watching French talk shows on TV. Besides exploring the city and making day trips to Chartres and Auvers-sur-Oise, I visited many museums, including the small ones (Bourdelle, Zadkine), and heard music at the Salle Pleyel (Krystian Zimerman), Cité de la Musique (Ensemble Intercontemporain in Carter, Kurtag and Dalbavie), Théâtre du Chatelet (Bluebeard’s Castle) and Bastille Opera (Renée Fleming in Manon). Meanwhile I practiced every day, and sometime in the middle of my stay, I called up Henri Dutilleux.

My visit to Henri Dutilleux was part of one of the most beautiful summers I’ve had. I stayed for several weeks in Paris just before beginning my doctoral degree. I was determined to pass out of the language-course requirement, so I rented a little apartment on the Rue du Cardinal-Lemoine and immersed myself in French, reading twenty pages a day, chatting with storepeople and watching French talk shows on TV. Besides exploring the city and making day trips to Chartres and Auvers-sur-Oise, I visited many museums, including the small ones (Bourdelle, Zadkine), and heard music at the Salle Pleyel (Krystian Zimerman), Cité de la Musique (Ensemble Intercontemporain in Carter, Kurtag and Dalbavie), Théâtre du Chatelet (Bluebeard’s Castle) and Bastille Opera (Renée Fleming in Manon). Meanwhile I practiced every day, and sometime in the middle of my stay, I called up Henri Dutilleux.

I recently saw Dutilleux’s short posthumous homage to Elliott Carter, in which he said that they did not meet much and that he had few specific memories besides of “a nice and strong character, a very charming man, and though we were far from each other – the Atlantic Ocean between us – I remain close to him and his music.” That June day was my only meeting with Dutilleux, but it was very meaningful for me to meet the creator of this music, and to play his substantial work under his curious and attentive gaze. He reminded me of certain great artists I’ve known, who share a simplicity and contentedness in their way of living that comes, I feel, from their satisfaction in their work and their love for what they do. Listening to recordings, I again relish his music’s generous ardor and stimulating clarity, luscious warmth, sweeping ebb and flow, big-band homophonic blocks of harmonies, and sense of spaciousness between the deep low register and the radiant highs. I respect his fastidiousness in composing but I dearly wish he had been more prolific in writing chamber and solo works that we could play and program. Having few pieces of his to play, I feel about his music much as I do about my meeting with him – truly delighted and wanting more chances to engage directly. He definitely left us wishing for more.

I recently saw Dutilleux’s short posthumous homage to Elliott Carter, in which he said that they did not meet much and that he had few specific memories besides of “a nice and strong character, a very charming man, and though we were far from each other – the Atlantic Ocean between us – I remain close to him and his music.” That June day was my only meeting with Dutilleux, but it was very meaningful for me to meet the creator of this music, and to play his substantial work under his curious and attentive gaze. He reminded me of certain great artists I’ve known, who share a simplicity and contentedness in their way of living that comes, I feel, from their satisfaction in their work and their love for what they do. Listening to recordings, I again relish his music’s generous ardor and stimulating clarity, luscious warmth, sweeping ebb and flow, big-band homophonic blocks of harmonies, and sense of spaciousness between the deep low register and the radiant highs. I respect his fastidiousness in composing but I dearly wish he had been more prolific in writing chamber and solo works that we could play and program. Having few pieces of his to play, I feel about his music much as I do about my meeting with him – truly delighted and wanting more chances to engage directly. He definitely left us wishing for more.