How should a symphony begin? Any way it wants. This symphony wants to begin quietly. Definitely no bombast. At all costs, avoid the gradual crescendo from niente to fortissimo, which has become a new music cliché.

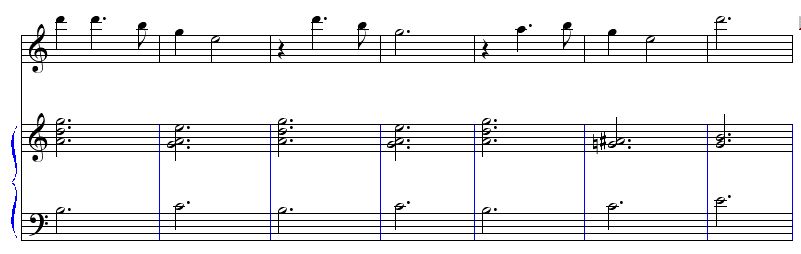

I heard a very straightforward tune in a moderate tempo for the opening:

I like the pentatonic simplicity of this melody -- it allows for polar opposites in presentation: it can be played with a childlike naiveté, harmonized in G Major, eg:

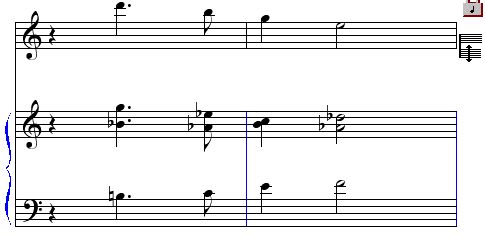

Or it can be the leading voice in a series of denser, symmetrical harmonies:

Which, when reversed, can take the listener in surprising directions:

It's an old but potent idea: the simpler the material, the more potential for development. Development, and even potential for development, don't guarantee great music, but they are nice to have at your disposal, just in case.

I initially heard this melody played quietly by the piccolo, accompanied by glassy string harmonics. But then I realized it would be very attractive, more elusive, played by the glockenspiel, with an occasional piccolo doubling. And that was the first music I wrote down for my symphony.

But as I said in my last post on this piece, the first music I write down is often discarded somewhere along the way. This melody was discarded after about 24 hours.

Resulting in a somewhat annoyed composer:

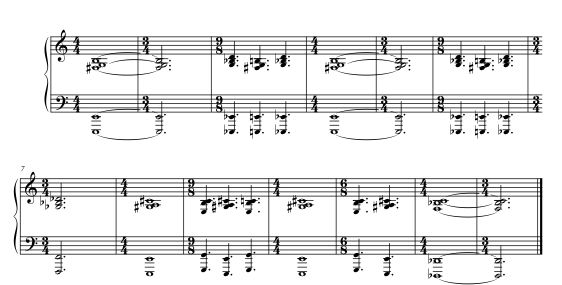

I may use this melody at some point in the piece. I will certainly use it somewhere eventually, but I lost interest in having it begin this symphony. Instead, I came up with the following progression of harmonies:

Why this progression, and what I’m doing with it, I’ll get to in a later post. For now, though, this is a good lesson in compositional discipline -- throw out more than you keep.