Beth Gibbons Astonishes in a New Górecki’s Third

After a decade-long studio hiatus, Beth Gibbons steps from behind the curtains with a project that feels as organic as it does surprising. Organic because its integration is undeniable, and surprising only to those unfamiliar with her trajectory. The Portishead frontwoman has always been known for her intensity as singer and songwriter, navigating a range uncommon both within and without the scene to which she has been aligned. The darkly inflected splash of Portishead’s 1994 debut, Dummy, threw her and bandmates Geoff Barrow and Adrian Utley into a drawer marked “Trip Hop,” a label that risked gessoing over the genre-defying shades of her vocal palette even as it gave listeners a viable canvas upon which to paint their appreciation. By 1997’s self-titled follow-up, strings had become a haunted theme of their sound, reaching ecstatic heights in such singles as “All Mine,” wherein Gibbons unleashed her soul through an emotional megaphone of fractured magnitude. All of this came to a head that same year when the band fronted a full orchestra at the Roseland Ballroom in New York City. The spirit of that concert seems to have planted a seed in the singer’s heart, easing her shift from a distance into the contemporary classical space of Henryk Górecki’s Symphony No. 3.

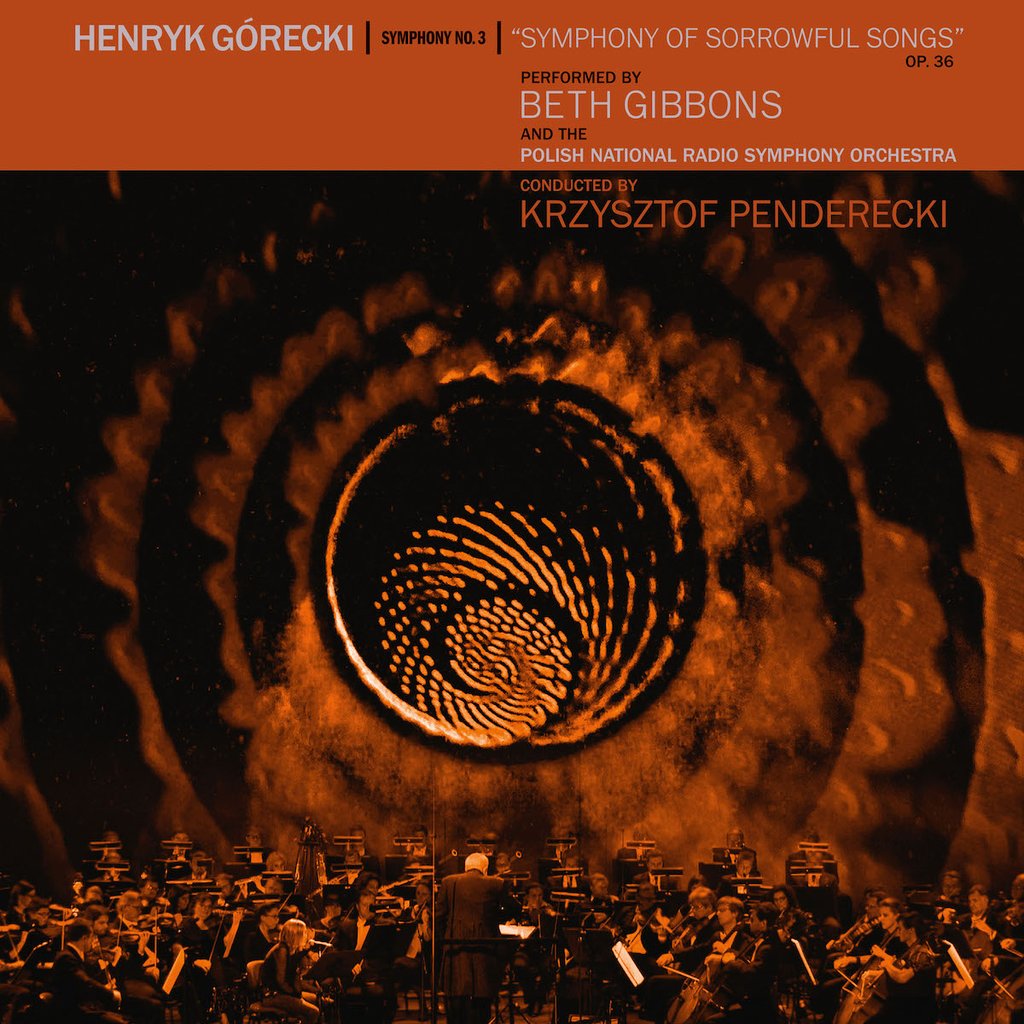

Those who grew up with the successful Nonesuch recording of this “Symphony of Sorrowful Songs,” featuring Dawn Upshaw and the London Sinfonietta under the baton of David Zinman, will have a thick cluster of brain cells to unravel in order to make room for yet another version, for since then a number of recordings, each with its merits, has appeared. Ewa Iżykowska’s on Dux (2017) arguably fills the finest diurnal cast, while Joanna Kozłowska’s on Decca (1995) is a close second for its cantata-leaning gradations. That said, and despite its muddy production, the Nonesuch blend of tempi and intimacy struck a profound chord with its 1992 release. For the present album we find ourselves in passionate redux. Given the current sociopolitical climate, when division has become the rule beyond exception, its immediacy is sure to ripple across the minds of new and familiar listeners alike. And if any conductor is worthy of ensuring that resonance, it’s Krzysztof Penderecki, here leading the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra in a live recording from 2014. Whether or not you agree with the concept (Górecki’s family reportedly wanted nothing to do with the project, and even Björk once turned down an offer to sing the Third), it’s difficult to push against the candor therein.

Long before Gibbons breaks the ice of our expectations, however, the violins in the first movement cry out with vocal integrity, enlivened by Penderecki’s own compositional reckonings with tragedy. The pacing is compelling yet offers enough breathing room for the piano’s restorative metronome. Gibbons makes an arresting entrance, noticeably different from predecessors not only in her ability to cut heart strings by force of a mere syllable but also for being fed through a microphone, thus lending an otherworldly appeal. Yet despite the technological intervention, if not also because of it, her honesty cultivates shared vulnerability. In that respect, it’s worth reminding ourselves of the words she’s singing—all too easy to forget when the meaning of this music has faded in favor of an effect cherished by popular imagination. Knowing that this centuries-old lamentation of a mother to her son occupies the center of an orchestral palindrome like a relic encased in glass provides insight into the worldview of a composer whose love for God embraced every note.

The second movement is built around an inscription by an 18-year-old girl to her mother found on a Gestapo prison wall. Unlike the desperate cries of innocence and revenge that surround it, Górecki was moved by its prayerful bid for forgiveness, unfettered by talons of war. Gibbons approaches this text with a remarkable combination of mature and childlike impulses, navigating both sides of life in poetic truth as Penderecki wraps her in a cloak of empathy. Her effort to understand the nuances of a language not natively her own, taking on the trauma of its becoming, is obvious and translates through her bravery.

The third and final movement centers around a folk song dating back to the 15th century, in which the Virgin Mary begs to share her Son’s wounds on the cross. The sheer humanity Gibbons draws from these verses shows in the urgency of her delivery as she follows the score with fluid precision, at once floating over and entrenching herself in the orchestra’s insistent pulse. In the process, she illuminates the fear churning at the bottom of all faith and the moral resignation required to turn it into knowledge.

Górecki once said in an interview: “I do not choose my listeners.” And yet, there’s a sense in which his music seeks out listeners more than ever, binding to flesh and spirit as if to make up for his death in 2010. All the more appropriate, then, that this piece should resurface in the present decade, when its connotations of genocide and sacrifice might ring truer even to those who once treated this symphony as a pretty backdrop. We live in harsh times when excuses for ignoring history are thinner than ever, and when a piece like this deserves a reboot to examine its inspirations more deeply. For while the Symphony No. 3 has been read above all as a critique of the Holocaust, Górecki clearly wanted to keep the font of his most personal work untainted by the fingertips of politics. If anything, an overwhelming maternity, compounded by the fact that the composer lost his own mother at the age of two, prevails, lighting a humble candle—not a universal torch—that continues to burn in his absence.

This album and its accompanying film are scheduled for a March 2019 release on Domino.