On June 4 and 5, the Synchromy Opera Festival presented two world premieres that explored the impact of modern technology on human relationships. The first of these, The Double, by Vera Ivanova, dealt with issues of identity and the reach of technology into psychological therapy. The second opera performed at the festival was Roman, by Ian Dicke, who is both composer and librettist. Roman takes takes an unflinching look at the sinister possibilities inherent in the commercial application of artificial intelligence. Ian Dicke is noted for his previous works that are also critical of modern developments: Get Rich Quick (2009) is a multimedia piece inspired by the financial crash of 2009. Unmanned (2013), a string quartet with electronic processing, delivers a troubling depiction of the use of drones in warfare. Roman, an opera, provides a much bigger artistic canvas and is one of Dicke’s more ambitious works.

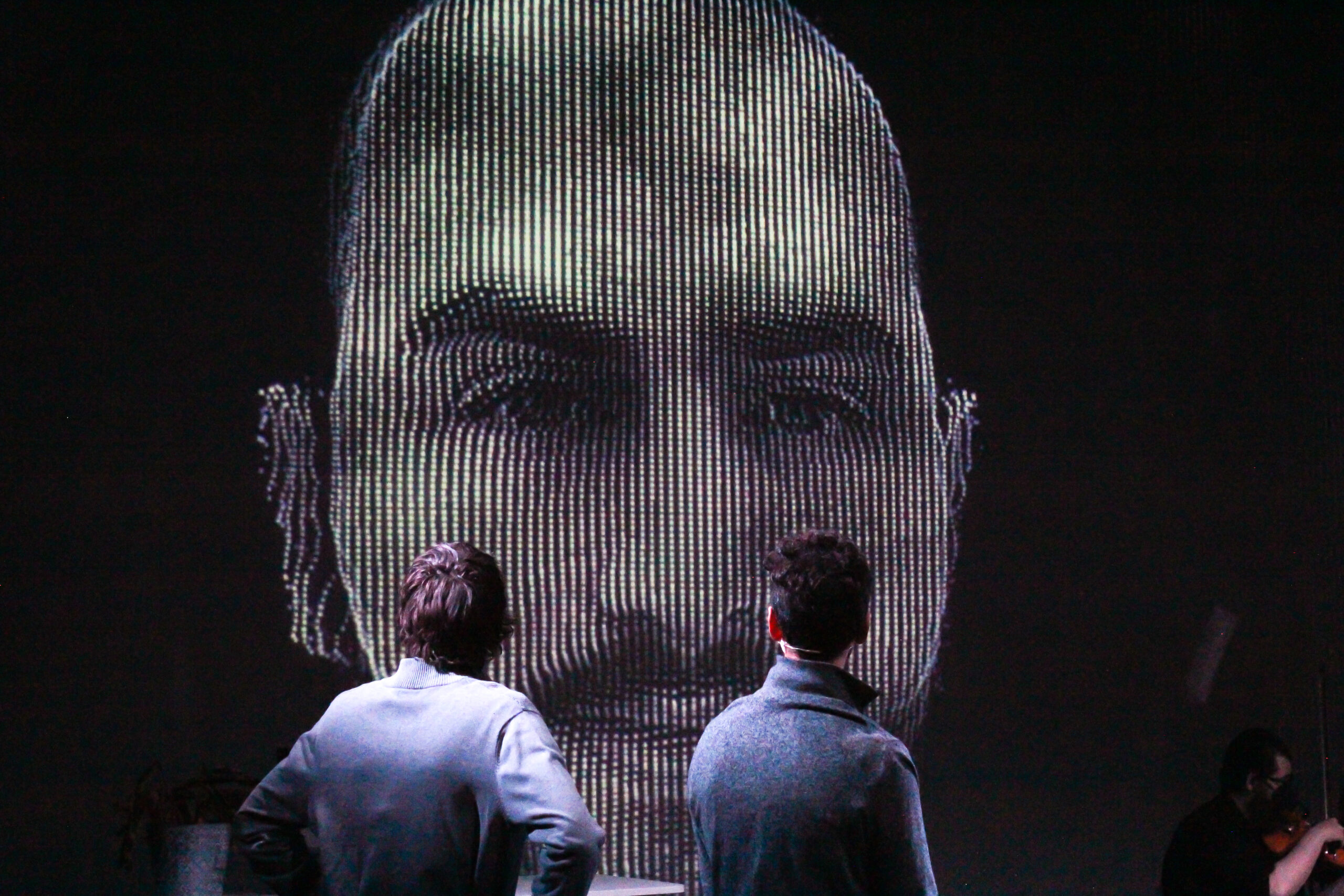

The musical accompaniment for Roman was provided by the Koan Quartet, seated along the rear of the stage and conducted by Thomas Buckley. Also included in the sounds are a number of electronic effects that are heard through a large speaker on the stage. The setting for the plot is a tech startup company and the scenery is spare – just a few chairs and a table. A large screen at the back of the stage provides for various projected effects and holds the computerized image of Roman, the avatar for a new artificial intelligence product that is under development. Only four singers, plus Roman, comprise the cast: the Inventor, sung by Elias Berezin, tenor, Employee 1 and Employee 2, sung by baritones Jonathan Byram and Luc Kliener, respectively and Lauren, the Marketing Director, sung by soprano Chloé Vaught.

The prologue opens with the Inventor busily programming Roman, or “Robot-Human”, designed by the company to be more than just hardware – it promises to be no less than “the future of companionship.” Roman has been given artificial intelligence and is programmed to absorb the nuances of human interactions processed from several thousand hours of video diaries compiled by his creators. A test of Roman’s ability to independently create music begins and the image of Roman fills the screen. His singing voice is a pleasant combination of the human and the synthetic. All this goes awry, however, when run-away synthetic sounds displace Roman’s human voice. A complete stop to the song indicates an emergency ‘power cycle’ by the Inventor – Roman went completely out of control and had to be unplugged. This failure is a serious setback in the development schedule, just as marketing promotion is set to begin.

At the start of Act I, the Inventor, Employee 1 and Employee 2 meet to try to put the project back on track. Roman sings “Am I broken?” as the Employees furiously try to correct the software as tensions mount. At this point Lauren, the young Marketing Director, enters. The Employees speak of her condescendingly, using overtly insensitive language and innuendo. All of this is silently absorbed by Roman who is programmed to observe and process human interactions.

Lauren announces her new marketing slogan for Roman: “Poetry in Emotion” and asks the Inventor for a demonstration. In response, Roman begins singing, sweetly at first, but the music rapidly turns louder, with a powerful beat and strong primal feel. The rhythms soon become broken and completely disconnected while Lauren is observed to be twitching out of control as if gripped by a seizure. Roman has apparently infected her cell phone with a virus that causes the battery to explode, killing Lauren, who falls to the stage motionless. The music turns very solemn and as Lauren’s spirit arises, the Koan string quartet plays a sweetly mournful benediction as the cast exits and the stage lights fade to darkness.

The final act opens in an arbitration court office, staged with a large conference table and a single chair. The Inventor sings wistfully about how Roman was developed with too much haste – “We wanted it all faster…” Roman appears on the screen and is confronted with Lauren’s death. “I am sorry to hear that’” he replies, but refuses to take any responsibility because he is “just a program.” The two Employees enter with the news that Lauren’s family will settle their suit for a mere ten million dollars, and that the Roman project can now go forward. The singing here turns to rationalization – Lauren died nobly in the pursuit of progress . There is one catch to the settlement, however: Roman must be renamed Lauren in honor of the deceased.

The spirit of Lauren appears and begins to take possession of Roman, who slowly dissolves digitally on the screen. In a final outburst, the dissembling Roman blurts out: “Why did I do it? Because I am you!” With the project restored, the singing by the Inventor and Employees turns triumphant: “Progress comes out of sacrifice. The world will be a better place!” At just this moment Lauren, now in full possession of her new powers, stuns everyone by whipping out her cell phone and shouting ominously: “Want to hear my new song?!” With that, the stage lights go instantly dark, the opera suddenly ends and the audience is left to ponder the chilling consequences of artificial intelligence.

The casting of Roman was exactly on target. The Employees looked and sounded like typically youthful computer nerds whose lack of social development and embedded misogyny infected Roman’s programming. The Inventor was suitably overbearing when necessary and also exhibited little respect for females like Lauren who needn’t be “bored with the technical details” of the project. Lauren was especially convincing as the character who was to die and then arise with a new personality. The singing by all was excellent and the active, almost continuous, playing of the Koan Quartet was ably performed and conducted. The stage direction, sound, lighting and costuming all complimented the production precisely.

The voice and projected image of Roman, the singing of the cast, the accompaniment of the Koan Quartet and all the other sounds coming from the stage speakers were a challenging mix for the technical crew, who nevertheless managed to integrate everything as and when the plot required. I was sitting near the stage and the output of the large speakers sometimes overwhelmed the singers, who often seemed to be singing in the same register as the accompaniment. It would have been helpful for the lyrics to have been transcribed to the screen. The many technical variables of this complex production, however, were otherwise successfully navigated.

Ian Dicke is a keen observer of social issues and this has informed his music over the years. Artificial intelligence is currently prominent in the public imagination and this opera was just the right vehicle to carry forward Dicke’s critical views of ‘progress.’ In a sense, this is an update of Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein – whenever mankind seeks to create life in his own image, it invariably includes our human flaws and leads to violence. Virtual life with artificial intelligence will be no different and in this telling, the sins of our cultural misogyny were readily absorbed into Roman’s personality. The shocking twist at the end makes a satisfying final statement: all of humanity is flawed. Roman is a brilliantly conceived work with great vision, artfully performed and is an opera that carries a sharp social commentary on a very pertinent topic.

Synchromy did an outstanding job of organizing, producing and staging Roman, proving that opera doesn’t have to be grand to be great.

Roman was a collaboration of:

Ian Dicke – Composer, Librettist

June Carryl – Director

Koan Quartet – Instrumental Accompaniment

Thomas Buckley – Conductor

Cast:

Elias Berezin, tenor – Inventor

Chloé Vaught, soprano – Lauren

Jonathan Byram, baritone – Employee 1

Luc Kleiner, baritone – Employee 2

Technical Crew:

Alejandro Melendez – Lighting Design

David Murakami – Projections

Nicholas Tipp – Sound Design

Natalia Castro – Costume Design

Sam Clevenger – Production Assistant

Photo by Madeline Main – Courtesty of Synchromy – used with permission