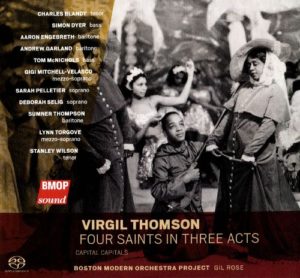

Virgil Thomson – Gertrude Stein

Four Saints in Three Acts; Capital Capitals

Charles Blandy, tenor; Simon Dyer, bass; Aaron Engebreth, baritone; Andrew Garland, baritone; Tom McNichols, bass; Gigi Mitchell-Velasco, mezzo-soprano; Sarah Pelletier, soprano; Deborah Selig, soprano; Sumner Thompson, baritone; Lynn Torgove, mezzo-soprano; Stanley Wilson, tenor;

Boston Modern Orchestra, Gil Rose, conductor

BMOP/Sound 1049 2xCD

Virgil Thomson’s 1934 collaboration with the eminent author Gertrude Stein resulted in their first of two operas, Four Saints in Three Acts. Boston Modern Orchestra Project, conducted by Gil Rose, has made successful forays into recorded opera before, bringing scores such as Lukas Foss’s Griffelkin and Charles Fussell’s Wilde to life. Their recording of Thomson/Stein’s opera is a very successful addition to the orchestra’s burgeoning catalog of works.

Taking Stein’s use of non-linear narrative in her writing as a cue, Thomson created a score that, for its time, was exceedingly adventurous. At first blush, one might well think of Thomson’s harmonic language – relentlessly tonal – and his borrowing of material from the American vernacular – ranging from hymns and folksongs to popular songs and dances – to be far more conservative than Ives or other contemporaries who mined similar material but with a more dissonant palette. There is also a component of repetition and scalar melismas, even counting that sounds like a cousin of passages in Philip Glass’s Einstein on the Beach, that suggests a proto-minimal approach to Thomson’s design. However, near-constant shifts of texture and demeanor, which mirror Stein’s approach to text, provide their own set of challenges for both musicians and listeners: in essence, how to follow the thread?

Four Saints in Three Acts is a work with a large cast, yet all of the roles in BMOP’s production are populated by fine singers, many of whom are associated with the Boston area’s various operatic ventures. The orchestra’s playing under Rose is also exemplary: this is a score in which frequent changes of instrumentation create a balancing act that could undo a lesser ensemble.

The liner notes are well curated. Given his totemic role as a writer on music, including Thomson’s essay about Four Saints is a particularly nice touch. Thomson scholar Steven Watson contributes his own enlightening essay, underscoring the durability of the opera through many production incarnations, from its original — an all African-American cast (most unusual for its day) — to Robert Wilson’s staging for huge animal costumes.

Capital Capitals is another Thomson/Stein collaboration, this one from 1927, for four male voices and piano. The text discusses the various virtues of “capital cities” — Aix, Arles, Avignon, and Les Baux — in Provence (Stein became acquainted with the region during her tenure as an ambulance driver in the First World War). It is breezier than Four Saints and proves an eminently charming counterpart.

_______

At 8 PM on Friday, March 31st at New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall, BMOP presents a concert featuring works by John Harbison, Eric Sawyer, Ronald Perera, and the world premiere of BMOP commission Black Noise by David Sanford. Soloists include violinist Miranda Cuckson, cellist Julia Bruskin, and pianist Andrea Lam. At 7 PM, a pre-concert lecture with the composers will be lead by Boston Symphony’s Robert Kirzinger. A repeat performance, this one with the Claremont Trio as soloists, will be at 3 PM on Sunday, April 2nd at Amherst College’s Buckley Recital Hall.